By William H. Thiesen, Historian, Coast Guard Atlantic Area

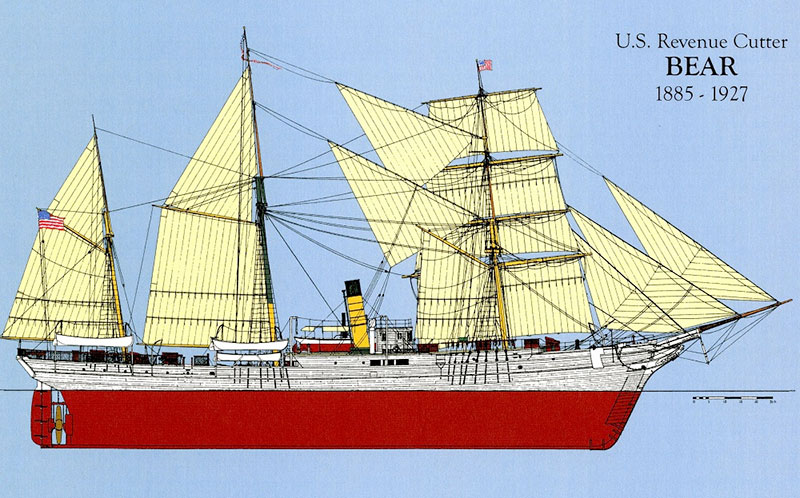

Colorized profile view showing hull and sail rig of Cutter Bear. Image courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard. Download image (jpg, 545 KB).

In 1885, Bear began its service career along with Thetis, an Arctic whaler turned over to the Revenue Cutter Service by the U.S. Navy. By today’s standards, these first revenue cutters to operate in the ice were considered “ice resistant” vessels.

Built in 1874, Bear was designed specifically to work in ice-bound conditions. She was a 198-foot, 700-ton barkentine rigged steamer constructed in Scotland for sealing in northern waters. In the 1800s, iron was considered too brittle for use in the cold Arctic, so Bear’s hull was built of wood, reinforced with six-inch thick oak planks and sheathed with Australian “ironwood” for a total hull thickness of 10 inches. Bear boasted a retractable propeller for less drag while sailing and it had extra space for fuel, supplies, or added passengers. It also had metal plating on its bow, allowing it to push through leads and openings in the ice without damaging its stem. Even though Bear carried a full sail rig, it relied on steam power to navigate through the ice.

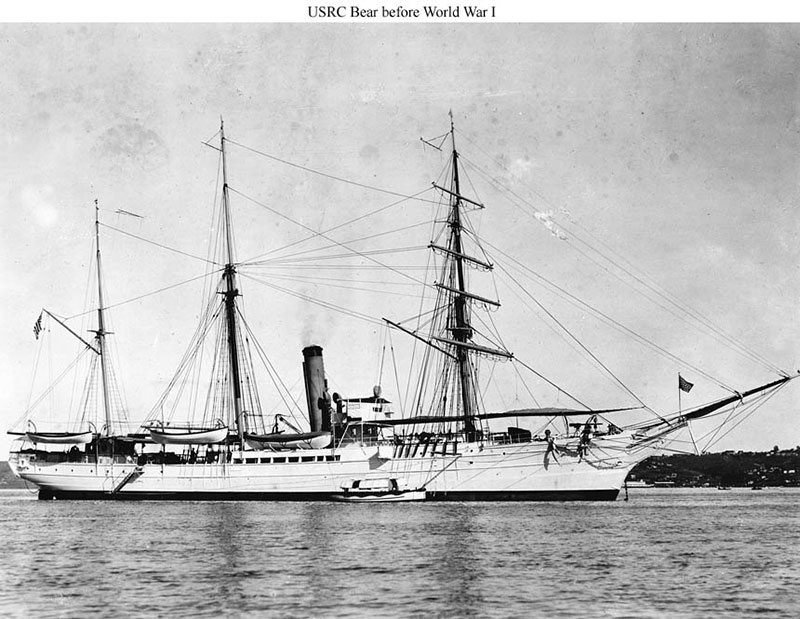

Close up of Bear mooring to a pier showing her hull and sail rig. Image courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard. Download image (jpg, 569 KB).

Bear proved effective only in the warmer months and normally did not steam north of the Arctic Circle in winter months. One of the few attempts to do so was the Overland Rescue, which began in November 1897, when Bear steamed north to relieve starving whalers trapped in the ice near Point Barrow, Alaska. Bear made it to Cape Vancouver, as far north as pack ice permitted, then disembarked a rescue team that drove a herd of reindeer 1,500 miles north to the icebound whalers. The rescue succeeded due to land-based dog sleds, while the cutter remained in the ice until the spring thaw.

Other revenue cutters carried on Alaska’s storied Bering Sea Patrol, but none of them had hulls reinforced to serve in the Arctic ice like the Bear and the Thetis. The next ice resistance cutter, Northland, was commissioned in 1927 when Bear was retired from the Coast Guard.

Full broadside view of Bear at anchor sometime in the early 20th century. Image courtesy of the U.S. Nay. Download image (jpg, 251 KB).