A large, wooden-stock, 19th century anchor, salvaged from the Northwest Reef area in the early 1970s, now lies partially buried and forgotten in the yard of an abandoned home on Providenciales. Could this be one of Chippewa or Onkahye’s anchors? Click image for larger view and image credit.

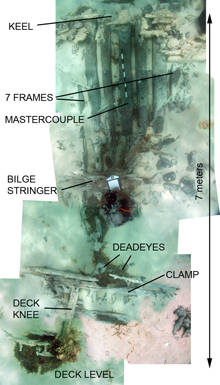

A photomosaic of the Black Rock Wreck’s hull components exposed in the transverse trench excavated across the site. The keel lies beneath the area where the frames end at the top of the mosaic, and the deck knee lies at the bottom left. The distance between these two points, seven meters, represents one side of the ship — from the keel to the bottom of the main deck. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Robert Krieble uses a diver propulsion vehicle (DVP) to explore the Drum Point Wreck. The remains of a steam winch lie in the lower right corner. Long, curving iron frames (as seen beneath the diver) preserve the shape of the ship’s hull. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Mission Summary

Donald H. Keith, PhD

Chief Scientist – The Search for the Slave Ship Trouvadore and the U.S. Navy Ships Chippewa and Onkahey

Every expedition’s worst nightmare is failure to accomplish the mission due to inclement weather. This consideration played an important part in planning our project for 2008. Although some of the reviewers of our original Ocean Explorer (OE) proposal questioned the wisdom of splitting our charter time between investigations in two widely-separated areas, our experience in the past taught us that you must always have a “Plan B.” Strong winds from the east, or even a tropical storm well out in the Atlantic, would prevent us from working on the north coast of East Caicos, where our primary objective, the Spanish slave ship Trouvadore (lost in 1841) lies.

For this and other reasons, we included in our application to the Turks and Caicos Department of Environment and Coastal Resources a request for permission to search for two U.S. Navy ships known to have been wrecked on or near Providenciales’ Northwest Reef. Although the reef itself is shallow and usually wave-swept, we knew we could conduct a survey there in almost any weather if we worked from small boats, while our mother ship lay safely moored in calm and deep water, less than a mile away in the lee of Providenciales.

Even before the expedition began, strong winds and large swells generated by Hurricane Bertha, well out in the Atlantic. made it impossible to work off East Caicos. We couldn't even ship the container loaded with our expedition equipment from the Turks and Caicos National Museum on Grand Turk to our mother ship, the Turks & Caicos Explorer II, docked at Providenciales (“Provo”). Instead, we sailed with minimal equipment for Provo’s Northwest Reef and began our search for the two U.S. Navy vessels. Engaged in slave ship interdiction and the suppression of piracy, the clipper brig Chippewa was lost in 1816, and the armed schooner Onkahey in 1848.

The magnetometer team spent two days surveying Northwest Reef, Wheeland Cut, and False Cut. Prevented by rough seas from approaching the reef too closely in their 27-foot (ft) boat, the "mag team" returned with few anomalies to report, and none that definitely indicated the presence of a shipwreck. Switching to the “low-tech” mode, two teams of swimmers and tow-boarders — operating from the Explorer’s small rigid inflatable boats (RIBs) — carefully worked their way into the reef. They were pleasantly surprised to discover that although it is sprinkled with coral heads, it is mostly flat with a uniform depth of about 6 ft. Despite the strong current running east-to-west across the reef, and the unceasing surge, a sweep with snorklers swimming line abreast located 5 carronades (short, large-bore cannons). These carronades, along with 5 or 6 others and an anchor (located subsequently), provided proof positive that we had found Chippewa.

After only three project days, we had mapped the readily identifiable remains and accumulated enough information to positively identify Chippewa, establish where it struck the reef, and determine the distribution pattern of the artifacts across the site from northeast to southwest. Our divers made an effort to approach the edge of the reef where Chippewa struck from the seaward side, hoping to locate the shot and anchors that we know were jettisoned or lost there, but the large swells and powerful surge made it too risky, and we turned back. Further exploration of that area in the future — to map the site and locate the rest of the ordnance, anchors, and other key artifacts — will require perfectly calm conditions. Clearly, Chippewa’s Captain Read mistook the reef between Wheeland Cut and False Cut for the northern tip of Northwest Reef and sailed into False Cut, thinking he was rounding Northwest Reef and entering the Caicos Pass.

But where was Onkahye? Months earlier, local informants told us about a mound of ballast stones on the northeast edge of the reef, lying between Wheeland and False Cuts. They showed us a 19th century anchor, now on land, thought to have been raised from that site. Cross-checking the location with their data, the mag team picked up a faint anomaly in the same place. We wanted to send a dive team to check it out, but it was too far from our mother ship’s mooring on the west side of Provo, and getting there would require taking our small inflatable boats well out to sea to clear the "fangs" of Northwest Reef. Clearly, a return expedition (and dead calm seas!) will be necessary to probe this promising target.

In any case, it was time to turn our attention to our main objective: to complete our instrument survey of the entire north coast of East Caicos, while simultaneously re-opening excavation of the previously located Black Rock Wreck, which we suspected is the Trouvadore. Most of our equipment was still at the Turk & Caicos National Museum on Grand Turk, and although it would cost us a day and a night to get there, we could not proceed without it. Catching a break in the pattern of high winds and seas, we made the 100-mile crossing from the Caicos Bank to Grand Turk, refueled, trucked our equipment to the dock, loaded it on board, re-crossed the Turks Island Pass, and dropped anchor in the lee of Drum Point — all in 24 hours. Here we rendezvoused with Officer Levardo Talbot of the Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI) Department of Environment and Coastal Resources, who was arriving from Provo in his shallow-draft, 33-ft motor-catamaran, and Robert Krieble in his 27-ft Boston Whaler from Pine Cay. The catamaran was moored directly over the Black Rock Wreck to serve as a surface-support platform for our dredge pumps, tools, hoses, and dive equipment, while the Whaler continued to serve as our magnetometer boat.

Local information and our magnetometer re-located a small iron cannon in shallow protected water near Jacksonville Cut during the East Caicos survey. It was not associated with any other artifacts or shipwreck site and may have been brought from elsewhere to serve as a mooring anchor. Click image for larger view and image credit.

It was a great relief to discover that the Black Rock Wreck showed no signs of having been tampered with since our last excavation there in 2006. Unlicensed treasure-hunting still plagues the TCI, as it does most places in the Caribbean region. In 2004, when we first discovered the Black Rock Wreck, we found abundant evidence that the site had been “blown” by someone using a prop-wash deflector. Since then we have been concerned for its safety, as it is located in a remote area off an uninhabited island. Over the next two weeks, teams of divers located and documented key features of the ship’s hull, enabling us to refine our estimates of the Black Rock Wreck’s length, width, displacement, rig, and the nature of its last voyage. We compared this information with what is known about the slave ship Trouvadore.

We confirmed the location of the mastercouple (the widest part of the hull and an important reference point for determining the dimensions of any vessel); exposed one side of the ship’s hull from keel to deck knee at the mastercouple; determined the angular relationship between the frames and the keel; located the bilge stringer, the probable locations of one mast mortise and the turn of the bilge, and the interior clamps; and recorded dimensions of the keel, garboard, hull planks, stringer, and deck knee. Intensive analysis of these key features and dimensions of the ship’s hull will enable us to further refine our estimates of the original vessel’s size and type. If we are correct in assuming that the frame bearing an “asterisk” carved into its side is the mastercouple, and that the “asterisk” is on the aft side of the mastercouple, then a measurement taken from the keel at the mastercouple to the top of the deck knee (allowing for the curvature of the hull) should give us a good estimate of the ship’s original maximum beam.

We removed sand from the southern end of the site, revealing broken and jumbled timbers and concreted fasteners, but we saw no evidence of an intact keel that would refine our estimate of the ship’s length. Excavation to the north revealed more continuous, if not contiguous, hull remains. At the end of the season, we had 28 meters (about 92 ft) of articulated remains and an overall site length of 35.5 meters (about 116 ft). The longer dimension includes what appears to be disarticulated remains distributed along the wreck’s longitudinal axis, and may not necessarily represent the ship’s original length.

Wood samples were taken in 2006 from the Black Rock Wreck’s principle timbers, such as the frames, keel, garboard, hull planking, clamp, and tree-nails. All the major timbers in the ship — including the keel, the frames, garboard, tree-nails — and outer hull planking are of white oak. The bilge stringer is southern yellow pine. The charcoal is probably eastern white pine. Two other samples taken from timbers with unknown structural functions are red oak. White oak is pandemic in distribution and is therefore not helpful in determining where the ship was built. The presence of southern yellow pine and eastern white pine hint at an origin on the east coast of North America, but these species also have a wide range, including Northern Europe. Furthermore, North American-built ships were as much in demand by Cuban slave smugglers as they were by legitimate North American traders.

In the absence of a “smoking gun” artifact, such as the carronades that allowed us to identify Chippewa, the only line of evidence we have to pursue is that offered by the ship’s archaeological remains, which are deeply buried in sand. All we know about the slave ship Trouvadore comes from references to it that appear in official correspondence: It was a brigantine of 111 tons burthen, built some time before 1841, operated by a Spanish and Portuguese crew taking as many as 289 Africans to Santiago, Cuba. There is no reference to where Trouvadore was built, or to any dimensions other than displacement. So far, although we have found no diagnostic artifacts that would prove the Black Rock Wreck is Trouvadore, neither has any of the evidence disproved its identity as Trouvadore. We will continue to analyze the hull data we collected this season, and to refine our understanding of the Black Rock Wreck.

What about other wreck sites (in addition to the Black Rock Wreck) that we found during our survey of the East Caicos reef? Two of them were small, non-commercial, 20th century sailboats; one was a large iron-hulled, steamship; and the one discovered this season was the marvelously intact wreck of a composite iron- and wood-framed sailing ship that had been carried over the reef at Drum Point and settled in the shallow waters of the lagoon behind it. Most other magnetic anomalies turned out to be either modern flotsam and jetsam not connected to any discernable shipwreck. One series of anomalies, however, appears to represent either another iron-hulled shipwreck, badly broken up and scattered, or a place where a large iron vessel was stranded but managed to escape after jettisoning some or all of its cargo of train wheels and axles. None of these sites could be Trouvadore.

Similarly, a compilation of all the ships known to have wrecked on East Caicos taken from newspaper accounts, dispatches from the U.S. Consulate on Grand Turk, the Northern Shipwrecks Database, the U.S. National Archives, and other primary and secondary sources, produces a list of almost a dozen vessel names. Could one of these be the Black Rock Wreck? No. Every ship on the list can be eliminated by its place of loss (a ship lost on Phillips Reef cannot have created a site at Black Rock), its dimensions (a vessel 65 ft in length could not have produced a site with articulated remains more than 90 ft in length), its type (iron steamships are automatically ruled out), or its date (commercial wooden sailing ships over 100 tons displacement built after the middle of the 19th century were typically strengthened with iron frame members and rigged with wire rope).

Having now completed a 100% visual and magnetic survey of the north coast of East Caicos, and two seasons of excavations, the Black Rock Wreck is still the only one that could be Trouvadore. We will spend the next several months analyzing the magnetometer and excavation data recovered during the 2008 season and expanding our historical research efforts in an effort to rule out — or conclusively prove — the identity of the Black Rock Wreck.

With respect to the U.S. Navy ships Chippewa and Onkahye, we are now working on a plan to return to the Northwest Reef of Providenciales next summer to locate and explore the site we think may be Onkahye and to continue our survey of the Chippewa wreck site. Meanwhile, the Turks and Caicos National Museum will increase its efforts to recover artifacts that may have been taken from these sites decades ago and are now in private hands.

Related Links

Ships of Exploration and Discovery Research

Turks and Caicos National Museum

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.