This heavily concreted carronade is one of 10 located during the Search for Trouvadore 2008 expedition. It is the proverbial “smoking gun” — the clue that every archaeologist hopes to find that will positively identify a site. By measuring the inside diameter, archaeologists confirmed that these were 32-pounder carronades, the size used on the Chippewa. Click image for larger view and image credit.

“ . . . the Brig, being the Act of turning over on her Starbd. Bilge, I was under the necessity of cutting away the Masts, the preservation of those left on the wreck had now become some what precarious . . .” This is how Master Commandant George C. Read described his effort to slow the destruction of the ship by cutting down the masts, a common practice on sailing ships. The remnants of the wooden mast deteriorated over time, but the stout mast band survives. Click image for larger view and image credit.

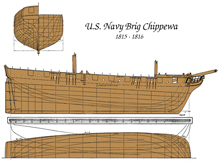

Chippewa was one of only three fast and well-armed clipper brigs specially designed and built to break the British blockade of American ports during the War of 1812. The construction and outfitting of the ship was done under the direction of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, who led American forces in a decisive naval victory at the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813. His battle report is now famous: "We have met the enemy and they are ours . . . .” Click image for larger view and image credit.

Identifying the Remains of the U.S. Brig Chippewa and the U.S. Schooner Onkahye

Donald H. Keith, PhD

Chief Scientist and Principal Investigator – The Search for Trouvadore, Chippewa, and Onkahye

Ships of Discovery

Toni L. Carrell, PhD

Co-principal Investigator – The Search for Trouvadore, Chippewa, and Onkahye

Ships of Discovery

We included the U.S. Navy vessels Chippewa and Onkahye in our plan of work for the Search for Trouvadore 2008 expedition because they illustrate a little-documented and little-researched aspect of the struggle to end piracy and slave trading in the first half of the 19th century. Remarkably, two ships that typify this aspect of history were wrecked in the tiny group of islands known as the Turks and Caicos.

Two lines of research led us to believe we already knew where to look for the ships: archival records and local knowledge. The archival records "told" us what to look for and how to make a positive ID from artifacts that are found. Information from local divers "told" us where artifacts that might have come from those vessels have been found in the past.

Existing archival sources describe Chippewa in detail. In addition to the U.S. Navy Court of Inquiry proceedings, these include a facsimile of its construction drawings, and its sail plan. Plans developed by shipwright William Doughty for Chippewa (and its sister brig Saranac) describe an 18-gun clipper brig with a length between perpendiculars of 108 feet; an outside beam of 29 feet, 9 inches; and a depth of hold of 13 feet, 9 inches. Contemporary accounts suggest Chippewa’s maximum draft was 16 feet, 6 inches, and that it displaced between 390 and 410 tons. But given the circumstances of how and where Chippewa wrecked, we knew it was unlikely that we would find much in the way of articulated hull structure. A more important potentially diagnostic feature would be the vessel’s cannons and anchors.

Although most secondary historical sources describe its battery as consisting of 16 guns, there is some disagreement in official naval correspondence regarding its actual complement of artillery. Originally, all of the Doughty-designed brigs were to be armed with two long 18-pounder cannons, two long 12-pounder cannons, and twelve 32-pounder carronades (also called cannonades). Interestingly it seems that the sister ships Saranac and Chippewa were armed with 14 carronades apiece, which would have increased their actual total complement of artillery from 16 to 18 guns. Regardless of exactly how many guns Chippewa carried, the 14 carronades alone would constitute sufficient evidence to make a positive identification because of their very distinctive shape and the brief time period during which they were used.

The carronade was a type of short, light, chambered ordnance of high caliber characterized by the presence of a central pivot loop cast on its underside, rather than trunnions (the cylindrical pivots on either side of a “normal” cannon's barrel), and an elevating screw behind the breech instead of a cascabel (the round button behind the breech). Carronades came into being around 1770, were most popular around 1800, and declined in popularity afterward. A 32-pounder carronade fired a 32-pound solid iron ball or shot, which would have had a diameter of about 6.3 inches.

We quickly discovered that although the top of Northwest Reef is shallow, flat, and swept clean by a strong current and constant wave action, corals flourish along the reef’s margin where it drops into deeper water. Our first discovery was a small mound of ballast stones garnished with a few concreted iron objects . . . not very exciting, but definite evidence of a shipwreck in the vicinity. Not long after, we sighted the first of the carronades. Over the next several days we swam much of the northern end of Northwest Reef, finding more carronades and other artifacts, including an anchor lodged in water so shallow one arm is visible in the surf. The bores of every carronade we measured (some bores were filled with coral or buried in the sand) were 6.4 inches, confirming that they were 32-pounders. This also confirmed we had identified the final resting place of the long forgotten U.S. brig Chippewa.

The fast, sleek, well-armed Chippewa is one of only a handful of U.S. Navy anti-piracy patrol ships whose wreck location is now known. The U.S. Navy never decommissions its ships, even when they are lost in battle or shipwrecked. Knowing that, we contacted the U.S. Navy Historical Center to tell them our intentions — even before we applied to the Turks and Caicos Department of Environment and Coastal Resources for a license to look for the Navy ships. With their blessing for our successful search, we were also given a permit to collect diagnostic or fragile artifacts from the site should it be necessary to help with identification.

And what about the other Navy vessel, the schooner Onkahye? We ran out of time before we could investigate a suspicious target detected by the magnetometer team a mile or two away from the Chippewa site, but we have every intention of returning next summer to continue the search. At some point in the not-too-distant future and with the approval of the U.S. Navy and the Turks and Caicos government, it may prove worthwhile to raise and conserve artifacts from Chippewa and Onkahye and put them on display along with those from the slave ship Trouvadore. Together they will to help tell the story of the part the Turks and Caicos Islands played in the international struggle to stamp out piracy and slavery and restore peace on the high seas.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.