Two “African Idols” referred to by George Gibbs, identified later as Kava-kava figurines from Easter Island, in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History. Image courtesy of Search for Trouvadore science team.

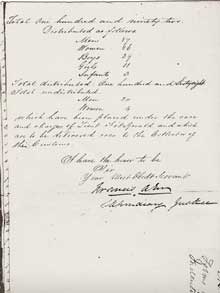

Page from 1878 correspondence from George Gibbs referring to the “African Idols” from the “last Spanish slaver to wreck on East Caicos”, in a group of accession documents at the Smithsonian Institution.

Trouvadore: Recovering the Lost Legacy of an African Slave Ship

July 8 – July 22, 2006

Donald H. Keith, Ph.D.

Toni L. Carrell, Ph. D.

Ships of Discovery

Veronica Veerkamp

Windward Media

The Trouvadore project began as a result of an investigation by Ships of Exploration and Discovery Research (SEDR) for the Turks & Caicos National Museum. The assignment was to research indigenous artifacts from other collections around the world for potential accession by the newly established museum. One of our first stops was the Smithsonian Institution, where we found a letter listing objects that a prominent Turks & Caicos Islander hoped to sell to the Smithsonian back in 1878. Among those objects was a reference to two “African idols” as having come from “the last Spanish slaver wrecked in the year 1841 at Breezy Point Caicos”.

No one in the islands could recall ever hearing of this shipwreck. Intrigued by the potential significance of the incident, SEDR conducted archival research in the US and Britain, Cuba, the Bahamas, Spain, and Africa. The investigation revealed that the mystery ship was Trouvadore, an illegal Spanish slave trader smuggling Africans to the market in Havana, Cuba. It wrecked while attempting to avoid American and British anti-piracy patrol vessels stationed in the Caribbean.

The wreck of Trouvadore was a major event in the tiny, thinly populated British colony composed of two island groups called the Turks & Caicos. It presented the residents with two distinct problems: what to do with the nearly 200 Africans saved from the wreck, and what to do with the ship's Captain and crew of Spanish and Portuguese sailors. Fortunately for 21st century researchers, finding solutions to these problems generated a lot of correspondence between the Islands' leaders and the seat of colonial government on Nassau in the Bahamas. Because slave trafficking in the British West Indies had been decreed a criminal offense in 1808 and slavery outlawed completely in 1833, the ship's crew was sent to Nassau in chains and imprisoned on their return to Cuba. The Africans were freed, but apprenticed to salt producers on Grand Turk who were charged with feeding and clothing them, as well as teaching them the English language and Christian ways.

According to contemporary population records, the human cargo of Trouvadore increased the population of the Turks Islands by 7 percent. The ultimate impact of their arrival was described in the letter by George Gibbs who noted that “they and their descendants form at the present time, 1878, the pith of our labouring population.” Unfortunately, little was written about the ship other than that it was a brigantine, was wrecked at Breezy Point, and that the total value of the ship's salvaged equipment was £71 3s.5d.

Over the years the story of Trouvadore was lost in the fog of time. Governments changed, climate, hurricanes, and neglect took their toll on records in the Islands until no trace of the story remained in written form and only vague remembrances of wrecked ships survived. One of the results is a general lack of awareness among the present population of the TCI of their African roots and the ship that brought their ancestors to the Islands. One of the main objectives of this project is to create a direct, very tangible, connection to their past and fill gaps in the nation’s cultural and sociological history.

Page from 1841 official correspondence listingthe Inventory of Africans taken from the Trouvadore. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Trouvadore and its story have import far beyond the shores of this small British West Indian colony. The 1841 incident epitomizes perhaps the least known era in the history of the African slave trade: the fifty-year period after it was banned by international treaty during which it flourished as never before.While official records and correspondence dealing with slavery and the effects of the slave trade during this time are abundant, slave smugglers kept few records due to their potentially incriminating information. Trouvadore’s story will help illuminate this largely hidden period in the history of slavery.

During the early to middle 1800s attitudes toward slavery changed and efforts to prevent the trade of Africans to the slave markets in the Americas grew. The British Navy began regular interdiction patrols off the coast of Africa and in the Caribbean. Eventually, even the United States Navy became involved and, as fate would have it, two US Navy ships were wrecked in the Turks & Caicos Islands during this period, Chippewa (1833) and Onkakye (1848), while on anti-slavery patrol.

Over the 400 years of the slave trade, hundreds of ships were wrecked, yet in spite of the vast amount of research conducted by slavery investigators, few of their remains have been recovered to touch, feel or examine. Of the slave ships that have been located and partially excavated, none of them were carrying slaves at the time they sank, and none have ever been scientifically excavated by archeologists. Trouvadore’s recovery would provide an extremely rare opportunity to study elements of the African slave trade that can only be realized by the hands-on examination of a working slave ship.