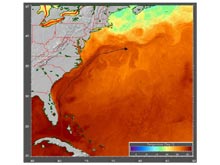

Figure 1. View of the Gulf Stream during summer off the southeastern United States. Darkest red colors (black line follows main current axis) are the warmest waters. The deep coral habitats sampled during our cruises are all underneath the Gulf Stream. It is a powerful force in the area, influencing marine ecology and weather patterns of the region. Our analysis of the history contained in the corals may help understand how this current has interacted with the area. Click image for larger view and image credit.

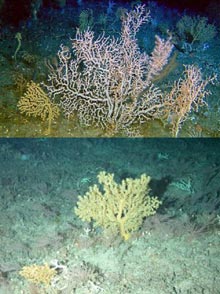

Figure 2.Black and Bamboo corals on the bottom on the Blake Plateau off the southeastern US in about 500-600 meters. We film and photograph these corals before collecting them to document their colors, their placement on the surface, and the other animals that use them for habitat. Some of these corals are bioluminescent (can produce light). Click image for larger view and image credit.

Vaults of History: Deep Corals as Archives

Steve W. Ross,

Chief Scientist/Lead PI

Center for Marine Science, University of North Carolina at Wilmington and

US Geological Survey

![]() Black coral (red) bush attached to the bottom on the Blake Plateau. (Quicktime, 346 Kb.)

Black coral (red) bush attached to the bottom on the Blake Plateau. (Quicktime, 346 Kb.)

Our planet and climate are changing. They always have and they always will. Scientists struggle to document and understand these changes, to determine their causes and their impacts. Understanding the planet’s history may allow us to better manage the present and prepare for the future. A large problem confronting this area of research is that planetary changes, such as climatological ones, often occur slowly over scales of hundreds, thousands or even millions of years. Adding to the difficulty of working on issues that span many generations, is the fact that during the long time span, significant environmental changes may be quite small. For instance, very small changes (a few degrees) in mean oceanic temperatures may eventually trigger massive changes in current circulation and climate patterns. The Gulf Stream is one such current affecting our study area. This combination of small scale changes over long time spans makes this type of research quite difficult.

Long term, accurate environmental records documented by observers or instruments are rare, and even the best ones span only a few decades. Scientific monitoring instruments simply have not been in place long enough to provide data on many topics for which we need information. To deal with this problem we turn to other ways such data are recorded. Layers of fossil materials are often used to interpret past conditions, and these can extend back for very long time periods. Long term ice fields, as in glaciers, have captured environmental snapshots of particular time periods and then been buried and saved. Cores from these fields can be interpreted for a variety of views about past conditions. Another means is to use very long lived organisms as proxies for environmental data. Most people are familiar with growth rings on trees, where each year the tree forms a ring whose thickness is related to environmental conditions affecting growth. Some trees can give very long records of growing conditions (warm versus cool, wet versus dry) in an area. In the deep sea, we are beginning to learn that a variety of corals are not only long lived, but also form growth rings at regular intervals. There is potential for a tremendous amount of data about the oceans and climates to be contained in these corals.

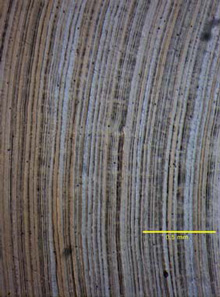

We are incorporating analysis of deep corals into our projects to

begin to construct a history of water temperatures, productivity,

and levels of pollution in the Atlantic Ocean off the southeastern

United States. The primary corals we will use for this part of our

research are the Black corals (antipatharians) and the gorgonian

corals (see Figure 3), especially Bamboo coral, which are present

through most of our study area from 360 to 800 m (and deeper). Because

these corals are slow growing, reach great ages, and may be slow

to recover, we only collect a few samples on each cruise, using the

submersible to pluck the coral from its attached substrate. Once

on the surface, we photograph the coral, take samples for genetics

studies, and then clean and dry the coral for later analysis. Back in

the laboratory the coral is identified and sliced into very

thin cross sections where the banding patterns can be seen (see Figure

4). Our data so far indicate that each band represents one year,

and we have collected black corals that range from 200 to 500 years

old (![]() Video

of Black Coral on the ocean bottom). After teasing apart these

very thin bands, each one is analyzed for a number of elements. So

far we have looked at Carbon and Nitrogen isotopes which have told

us that there has been an increasing input of nutrients reaching

the deep sea. It appears that these nutrients were land-derived.

We are beginning to look at other isotopes and metals (such as lead,

zinc, chromium, magnesium, barium, strontium, calcium, and others).

Determining these patterns in chemical signatures recorded in annual

bands of corals over hundreds of years over a large geographic area

and large depth range will give us powerful tools for interpreting

how natural and human induced changes have affected the oceans.

Video

of Black Coral on the ocean bottom). After teasing apart these

very thin bands, each one is analyzed for a number of elements. So

far we have looked at Carbon and Nitrogen isotopes which have told

us that there has been an increasing input of nutrients reaching

the deep sea. It appears that these nutrients were land-derived.

We are beginning to look at other isotopes and metals (such as lead,

zinc, chromium, magnesium, barium, strontium, calcium, and others).

Determining these patterns in chemical signatures recorded in annual

bands of corals over hundreds of years over a large geographic area

and large depth range will give us powerful tools for interpreting

how natural and human induced changes have affected the oceans.