Up From the Zone of Trees

May 12, 2004

Mary Grady

Adjunct Earth Science Instructor

Northeastern University

We can only sense that in the deep and turbulent recesses of the sea are hidden mysteries far greater than any we have solved.

—Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us

Late Tuesday night, as Hercules began to send images back from the slope of Bear Seamount, scientists watched the big plasma screen in the main lab and crowded into the control van. In the first few hours, a gorgeous white chimaera fish swam gracefully—seeming to fly—above a sandy substrate. We spotted several halosaur fishes, many of them hanging vertically in the water column, their long tails flexing like banners in the wind. It wasn't until about 2 am that basalt rock began to appear, revealing an interesting benthic (bottom-dwelling) community.

Dr. Jon Moore, Dr. Peter Auster, and Mike McKee take their turns on watch in the control van. Click image for larger view.

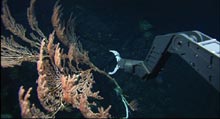

All through the night, Hercules sent back spectacular images. We found a variety of corals, urchins, sponges, and sea stars, which gradually filled the bio box. Around 10 pm, the bio box got stuck, and the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) pilots couldn't close it. They tried bumping it against the rocky slope, and finally positioned both manipulator arms to push it shut. Soon after that, the ROV headed for the surface.

IFE ROV Hercules collecting a Keratoisis "bamboo" coral on Bear Seamount. Keratoisis produces a bioluminescent blue-green light when agitated. Click image for larger view.

In the early afternoon, Hercules and Argus surfaced. The scientists gathered around the bio box. Most samples had to be processed immediately, before they began to deteriorate and die. A thick black coral oozed mucus. "You have to work quickly or the tissues just start to turn to mush," said graduate student Anne Simpson.

Scientists rarely have the chance to learn about these deep-sea species so every observation is new and interesting. "I've noticed that the colors of the brittle stars seem to match the colors of their hosts [the coral stalks]," said Dr. Lauren Mullineaux. "Why should that be, when there's no light down there?" Dr. Les Watling, chief scientist, had no answer beyond, "I wish I knew." The bright colors of many of the corals and urchins seen on the video are a nagging mystery to the scientists.

Chief scientist Les Watling (right) and Scott France examine a black coral specimen just taken out of the bio box on the ROV Hercules. Note their animated reactions to the mucus oozing off the coral. Click image for larger view.

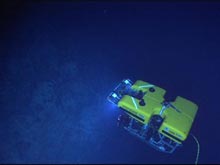

IFE ROV Hercules climbing the side of Bear Seamount, as seen from a camera mounted on Argus. Click image for larger view.

Researchers processed samples throughout the afternoon. Tiny branches from fragile corals were snipped, dunked into ethanol-filled tubes, sealed, and labeled. The samples will be used for genetic tests. Another piece of coral prompted a detailed discussion about the "weirdness" of its polyps. Finally, Dr. Scott France orchestrated a quick show in the freezer room: a long bamboo coral, more than a half-inch thick, lay tangled in a five-gallon bucket. Dr. France turned off the lights, gently tapped the coral a few times with a plastic ruler, and the coral sent off rays of greenish-blue light. Why it does that is yet another mystery. Does it frighten off predators? What kind of predator would that be?

Graduate student Mercer Brugler processes samples by preserving them in ethanol. Click image for larger view.

Very little is known about these animals. In the 1800s, fishermen occasionally would snare the deep-sea corals in their nets. The region where the corals were found was called "The Zone of Sea Trees," noted Dr. Les Watling. "They have the morphology of plants, and some of them were really big —six or seven feet — so they were described as trees. They were known to exist, long before we had the technology to go down and look at them."

Now that we can, scientists are hurrying to observe them before they suffer the fate of many shallow-water coral communities. "We need to understand how these corals reproduce, if they migrate, and how far they can go," said Dr. Scott France. "Are the corals on Bear Seamount the same species as those on Manning? Or have they been isolated and evolved into separate species, like Darwin's finches on the Galapagos? How critical are the coral colonies to the fish populations? If we understand these things, we can try to predict how these communities could recover—or not—once they're disturbed."

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.