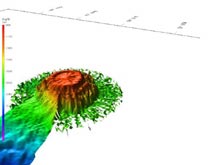

Data acquired with the Ronald H. Brown SeaBeam system produced this multibeam image of Bear Seamount. The summit's concave appearance is an artifact, which resulted during data acquisition, when the ship "hovered" above the summit. Click image for larger view.

Dry Run in the Wet

May 10, 2004

Mary Grady

Adjunct Earth Science Instructor

Northeastern University

All we do is touched with ocean, yet we remain on the shore of what we know.

— Richard Wilbur

![]() See an animated fly through of Bear Seamount, created using analyzed multibeam data. (mp4, 1.75 MB)

See an animated fly through of Bear Seamount, created using analyzed multibeam data. (mp4, 1.75 MB)

By early Monday morning, the ship had reached the waters above Bear Seamount and attained a stable position. Researchers acquired SeaBeam bathymetric data both in transit and at Bear Seamount. They compared this data (gathered with the newly installed system) with data from past expeditions to Bear. Some obvious artifacts in the newly acquired data include those due to pitch and roll and beam geometry: these will be corrected once we are able to run a few tests over relatively uniform terrain. Another artifact appeared at the summit, where the ship "hovered" with the SeaBeam system running. As a result, the summit appears concave, although previous expeditions and data sets demonstrate that this is not the case. University of Maine graduate student, Allan Gontz, will "clean up" the data. The new data will be merged with the previously collected data to develop a more complete high-resolution bathymetric image of Bear Seamount.

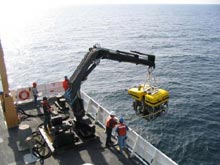

The hours rolled past as technicians and engineers tweaked, tested, and peered intently at their machinery; talked through headsets; and worked through checklists. Meanwhile, the science team busily planned out the details of their tasks; reviewed data from past exploration; and trained some newer crew members and graduate students on their data-logging duties. Every few minutes someone would ask, "Won't the ROV [remotely operated vehicle] get launched today? Does anybody know when?" But everyone knows that, for this first deployment, the best thing is to leave the technicians alone and let them take their time. When will the ROV launch? When it's ready! This is the only answer that's forthcoming—and the only answer that makes sense.

Finally, at about 2 pm, the Argus tow sled was let down gently off the stern and into the sea. A thick, 4,000-m, steel line, rolled on a massive winch on the deck, tethers Argus to the ship. Hercules, connected to Argus with a long blue-and-yellow cable, follows next. Nature couldn't be kinder, giving us nearly flat seas, a thin overcast, and hardly any wind. Right from the start, a three-ft-wide plasma screen in the main science lab lights up with the video feed. The first view shows Hercules’ bio box (where samples will be stored) and its long manipulator arm, glowing in the reflection of the ROV's lights, as the robot sinks slowly in the darkness toward the top of the seamount. The scientists gather and gaze.

"Ooh's" and "ahh's" accompany each glimpse of a darting fish, a luminescent copepod. "Oh! Did you see that? It looked like an eel." "Whoa! That might have been a squid." "That was a sea butterfly . . . a Gonionena jellyfish . . ." "Look at all that bioluminescence—it sparkles." Tiny bright particles flurry by as Hercules sinks. "They look like little cephalopods," said Dr. Jon Moore, "drawn to the light, like moths." Bright red and glowing white creatures dart past. It's kind of like watching fireworks in slow motion.

The camera pans away to reveal a wider view of the water column. Then it begins to look around, checking its own gauges—still far to go on the PSI meter—then returning to the water-column show. For this first dive, the control van is off-limits. Only Dr. Peter Auster, who is one of the group's leaders, and Mike McKee, the data manager, are allowed in there during the descent. Once the ROV reaches the top of the seamount, the scientists will start to rotate through on one-hour shifts.

But the ROV doesn't make it to the summit. Suddenly, in the science lab, the screen goes dark. A scout to the aft deck comes back to say the winch had stopped turning. A few minutes later, we hear the report that it's turning again — but in reverse. It takes almost an hour to pull Argus and Hercules back to the surface, and secure them in their places on deck. Early reports said the control cable between the two machines suffered some kind of internal breakage. The good news is, there's a spare cable on board. The plan is to make the fix and try for another dive sometime before midnight.

IFE ROV technicians/pilots Tom Orvosh (left) and Dave Wright work to disconnect the fiber optic cable from Hercules. Click image for larger view.

IFE computer technician Webb Pinner and IFE ROV technician/pilot Tom Orvosh coil up the fiber optic cable. Click image for larger view.

The ROVs are still cutting-edge technology. Many of the scientists on board have limited experience with them, especially ones as big and complex as Hercules. Dr. Scott France, who studies the genetics of deep-sea corals, has explored this region using the DSV Alvin, but this is his first experience with ROVs. How will using this different technology affect his research? "Ask me again in 14 days," he said. "I'm not really sure. But I think the ROV will actually be more capable in getting done what I want to get done." One advantage of the ROV is that it has a constant power supply and can spend more time at the bottom. This gives France more opportunities to find and collect the samples he needs. "On the other hand," he said, "DSV Alvin has a greater capacity for carrying samples to the surface."

Dr. Scott France works in the science lab as the science party awaits a second try to get the ROV to the base of Bear Seamount. Image courtesy M. Grady.

IFE team members Louis Whitcomb (left) and Jon Howland discuss possible scenarios for the ROV power failures in the control van. Click image for larger view.

Dr. Les Watling, the mission's chief scientist, is also eager to see how the ROVs will enhance his data collection. Will it give him more opportunities to explore more of the terrain than Alvin did? "I'm not sure," he said. "We'll just have to wait and see how it goes." The ROV doesn't go any deeper than Alvin can. "But one advantage of the ROV," Watling said, "is that the team of scientists can work together, watching the video screens, to make communal decisions about where to go and what to collect—in real-time. When you're down at the bottom in Alvin, you're pretty much on your own. Communication with the scientists at the surface is pretty limited."

Today, on our lonely ship, we encountered two life forms out here besides us: a huge whale breached just by the aft stern deck, rolled on his back and smashed out a wave. And, we saw a tiny yellow-and-brown wood warbler, not more than 3 or 4 in from beak to tail, wandering on the weather deck, nearly 200 mi from shore. The whale seemed exuberant, the warbler merely weary. Beyond these two, there is only our ship alone out here, in the middle of a dark-blue sea that stretches in every direction to meet the sky.

This small wood warbler was presumably blown off course while migrating from its winter home in Central or South America. Click image for larger view.

The Hazards of Migration

Dr. Scott C. France

Assistant Professor

Department of Biology

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Co-Principal Investigator – Mountains in the Sea

This afternoon a small wood warbler, typically found catching insects off trees in northern forests, landed on the ship. Presumably, it was blown off course while migrating from its winter home in Central or South America. It appeared exhausted, and sat fairly quietly on the deck in the shadow of cables, the A-frame, and an ROV van. Warblers are one of many birds that migrate long distances between summer breeding grounds and winter ranges. Many birds do not survive the journey, falling victim to a number of dangers along the way. This perilous, long-distance journey reminds me of the situation facing deep-seamount corals. In order to get from one seamount to another, coral larvae must cross an expanse of water several thousand meters deep and be lucky enough to be carried by ocean currents to an appropriate surface to settle. How many larvae are able to make this journey rather than being eaten or carried off into the open ocean? This is one of the questions we are exploring on our expedition.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.