Tracklines of the multibeam bathymetry cruises. Green indicates data collected during September 2002 and red indicates data collected during February-March 2003. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Cruise Summary and Results

Leg I: September 24-30, 2002

Leg II: February 18-March 7, 2003

Uri ten Brink, Chief Scientist

U.S. Geological Survey

Despite its fascinating and mysterious origin and the potential hazard it poses to Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, the Puerto Rico Trench has not undergone much study during the past 25 years. Our technical capabilities to explore the oceans have improved tremendously during that period. NOAA's Office of Ocean Exploration identified the Puerto Rico Trench, the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, as a prime target for exploration and funded two expeditions to map the trench and its vicinity. Mapping was conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) aboard the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown in cooperation with the NOAA/University of New Hampshire Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping and the National Ocean Service's Office of Coast Survey.

These mapping data, acquired and processed during the first six days of Leg II of the expedition, demonstrate the time involved in mapping a very deep region of the ocean. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Multibeam bathymetry and acoustic backscatter data were acquired for 27 days. The expedition mapped the Caribbean plate, an entire tectonic province of the Earth, encompassing approximately 22,700 sq nautical miles. The survey was unusual in both its scope and the depth at which it was conducted. Only a thin layer of sediments covers most of the trench floor and its vicinity; therefore, the picture that emerged from these maps indicated a deformation created by large plate tectonic forces. The pattern of deformation was then used to assess the seismic and tsunami hazards of the area.

The major discoveries made during the expedition included the following:

- The deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean is at a depth of almost 8,400 m (5.2 miles). It is an elongate and very flat depression, 280 km (175 miles) long.

- The North American tectonic plate, which lies north of the trench, is descending under the Puerto Rico and Virgin Island blocks south of the trench. The large submarine slides on the downgoing plate suggest that the bottom of the trench may have deepened recently (see the essay, "Trench", for details).

- The southern side of the trench, north of Puerto Rico, is covered with a tilted limestone layer. The top of this layer is very smooth except for the presence of narrow deep gullies. The deep edge of the layer is jagged with evidence of large scale slumping. Several cracks were detected near the edge, which suggests that the process of slumping continues today.

- A large fault system, which is similar to the San Andreas Fault in California, was discovered in very deep water near the trench. Much of the horizontal sliding between the North American and Caribbean plates occurs along this fault. The fault was named after Dr. Elizabeth (Betty) Bunce, a marine geophysicist pioneer who investigated this challenging environment in the 1950s.

Dr. Uri ten Brink presents Dr. Elizabeth (Betty) Bunce with a colorful poster with maps and images of the fault bearing her name during a small ceremony earlier this year. Also present were Hartley Hoskins, Dave du Bois and Dicky Allison of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Dan Blackwood of the USGS. Click image for larger view and image credit.

- Bunce Fault is located 115 km north of Puerto Rico. Previous interpretations placed active strike-slip faults as close as 55 km from the northern coast of Puerto Rico, which would have implied a greater seismic hazard to Puerto Rico. In addition, the Bunce Fault passes through an area of relatively low bathymetric relief, which is less prone to large, seismically activated submarine slides than faults crossing the steep slope north of Puerto Rico.

- In contrast, Bunce Fault interacts with other fault systems to the northeast and northwest of Puerto Rico, producing high rates of seismicity and dramatic topography.

- A mud volcano, which spewed saturated mud to a distance of 10 km, was discovered at a depth of 7,900 m.

- The North American plate, which descends into the trench, is broken into steps with vertical offsets from 0.5 to 1 km, and is sheared parallel to the trench. Such extensive deformation is unusual in the descending slab.

These exciting discoveries will form the basis for additional expeditions that will investigate specific features of the sea floor by means of submersibles and remotely operated vehicles.

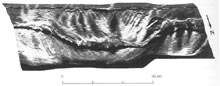

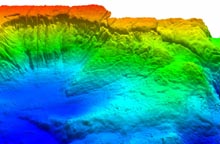

Figure 1. 3-D view of the scarp looking south toward Puerto Rico. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Submarine Slides North of Puerto Rico: Implications for Tsunami Hazard

By Uri ten Brink, Chief Scientist

U.S. Geological Survey

A large amphitheater-shaped scarp (a line of cliffs produced by faulting or erosion), 55 km across, is located on the northern insular slope of Puerto Rico, 37 km north of the city of Arecibo. The USGS first discovered the scarp in the 1980s while mapping the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), utilizing the GLORIA system, a long-range side-scan sonar. It was interpreted as a giant submarine slide that removed 1,500 sq km of the Tertiary layer, which was covered by a thick (1,300-1,500 m) sequence of carbonate rocks. Figure 1 is a 3-D view of the scarp looking south toward Puerto Rico. In 1990, it took one month to generate this single image. Much higher resolution images, created in near real-time from this multibeam bathymetry survey (Figure 2), show the morphology of this scarp failure in greater detail.

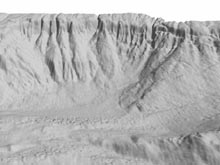

Figures 2a and 2b. Two views of the same slide imaged by the multibeam bathymetry method. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The scarp was interpreted to represent a large-scale slope failure that was probably caused by the tectonic oversteepening of the insular shelf. The carbonate layers, which were deposited horizontally near sea level until 3.3 million years ago, are now tilted approximately 4.5 degrees to the north, reaching a depth of almost 4,000 m near the edge of the scarp. The uppermost surface of these carbonate layers appears as a relatively featureless sloping sea floor south of the scarp (Figure 2b). The slope maintains its angle as it continues upward across the northern shore of Puerto Rico and into the hills above San Juan.

Until now, it was unclear whether the northern insular slope of Puerto Rico continued to tilt and if submarine slides were still active; however, the newly acquired multibeam data and imagery suggest that the slope failure was an initial phase in the landslide process. The top portion of the carbonate platform and underlying strata had simply collapsed downslope, causing the foot of the slope to steepen. This interpretation is supported by the lack of large quantities of slide debris farther north. A crack can also be seen continuing eastward below the edge of the carbonate platform (Figure 2b), and smaller slumps are observed below this crack.

Additional cracks on the sea floor on the upper left side of Figure 2b appear to isolate a 7x3 km polygon of sea floor at the head of the scarp, which is slightly sunken relative to the surrounding area. This polygon may be an initial slump, which may cause a large part of the slope to fail in the future. These observations suggest that slumping along the northern slope of Puerto Rico is an active and ongoing process.

Submarine slides are known sources of tsunamis; the sudden vertical displacement of a large volume of the sea floor during slope failure displaces the overlying water mass, generating a "tidal" wave. One such slide in Papua New Guinea, the result of an earthquake in 1998, caused a massive tsunami with more than 2,100 casualties. The discoveries made during this expedition make clear the potential tsunami hazard to the densely populated northern coast of Puerto Rico if another massive slope failure were to occur during an earthquake.