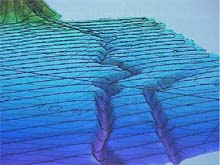

A three-dimensional image of our mapping efforts of the Hudson Canyon. Horizontal black lines indicate our mapping tracklines. Contour lines, also showing, connect points of equal magnitude above and below the seafloor surface. (Note: image shown with vertical exaggeration to highlight features) Click image for larger view.

Questions and Answers with

Dr. Peter Rona, Chief Scientist :

Hudson Canyon Exploration Cruise

of the NOAA Ship Ron Brown

September 8, 2002

Lisa M. Weiss, Watershed Coordinator

Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve

We are about two weeks into the Hudson Canyon Exploration. If you were watching us from above, you would see nothing more than the Ron Brown making its way continuously back and forth across a 60-mile-wide piece of the Atlantic Ocean. If you were lucky enough to catch us at the right time, you might get to see us sitting in a stationary position, lowering something from the deck into the water. Then about two or three hours later, you would see us pulling that instrument back onto the deck. Of course then we resume our more "natural" pattern of motoring along, back and forth.

What is this mission that we are on? What can we expect to take away from this mapping exploration? Why is this area of such great importance? How can the people back at home relate to our operations?

These were the questions that I asked Dr. Rona, the Chief Scientist for the Hudson Canyon Exploration Cruise. With one week left of our trip, it was time to put our science investigations into context. There is more to what we are doing out here than "mowing the lawn." But, if only 5 percent of the world’s oceans are mapped in this detail, why are we concentrating on this one area off the coast of New York and New Jersey? Our extensive exploration will help scientists and the public gain a higher appreciation for an small piece of the ocean that is in our own backyard.

Chief Scientist, Dr. Peter Rona explains to me how mapping the Hudson Canyon may impact the underwater, Trans-Atlantic fiber-optic telecommunication cables. These are the telephone connections that run from NewYork City, all the way across the Atlantic Ocean. Click image for larger view.

Why invest in the Hudson Canyon?

As Dr. Rona pointed out, if we were to remove all the ocean water in the Western North Atlantic from the southern tip of Florida to the northern end of Canada, one would see that the Hudson Canyon is the largest submarine canyon on the eastern margin of North America. Extending from the mouth of the Hudson River, in the middle of New York City, the Hudson Canyon extends 300 miles beneath the ocean, connecting the heart of New York with the deep ocean. According to Dr. Rona, as soon as we travel offshore we are in a vast ocean wilderness, one in which the further offshore we travel, the less we know about the ocean, its processes, creatures and underwater topography.

He explained that submarine canyons are conduits, or pathways, from the land to the sea. As silt, sand and mud are carried down the Hudson River, they flow into the canyons and then out into the deep ocean. It is possible that the Hudson Canyon is actually being cut from traveling sediments. As Dr. Rona described, the Hudson Canyon is particularly interesting because it originates in the heart of the largest metropolitan area in the world and is immense. Not only might the Hudson Canyon carry sediment, but it could also be carrying pollutants that are washed into it through the Hudson River and the surrounding coastal zone.

Why is the Ron Brown steaming around the Northern Atlantic Ocean for 20 days? What can we expect to learn from this ocean exploration? How will a better understanding of the Hudson Submarine Canyon affect you back at home? Click image for larger view.

The best way to think about this is from a watershed perspective. Pollutants that are on land eventually make their way into the water via surface water run-off. When these pollutants wash into the waterways, they will eventually make it into a river that will eventually lead out into an ocean. All the pollutants from land that have been accumulating in the waterways that drain into the Hudson River will drain into the Hudson Canyon. By mapping this area, we will learn more about the pathways of these sediments and potential pollutants. In the future, we will sample the Hudson Canyon sediments for pollution. If there is pollution draining into the Hudson Canyon, where does it go, what happens to it , and how does it impact ocean life?

Dr. Rona also pointed out that the Hudson Canyon region is a hub of trans-Atlantic fiber-optic telecommunications cables that connect the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area to the rest of the world. By mapping the Hudson Canyon, we will know better where to put these types of cables in the future.

Why does our mapping include such a large area around the Canyon?

According to Dr. Rona, the geologic processes occurring at the Hudson Canyon extend way beyond the canyon itself. Although the Hudson Canyon is the focal point of our investigations, we are mapping a larger area to understand all the processes that occur, even in the surrounding areas.

Kyle and Tammie working on editing during their four-hour watch. Seafloor mapping, of the quality that we are doing on the Hudson Canyon, means quality control and assurance of the data. Every hour of data that is collected is made into a separate file which has to be hand-edited. Click image for larger view.

How does the Sub-bottom profiling add to the Hudson Canyon mapping?

The mapping is just the tip of the iceberg. Dr. Rona says that we really need to look below the seafloor. The sub-bottom profiler uses a lower sound frequency that allows us to see just beneath the seafloor (a few hundred feet) to the sedimentary layers. This type of investigation is important in understanding the processes of erosion and sediment deposition within and around the canyon.

How does water sampling and mapping fit together?

In addition to the mapping project, our exploration is also testing the theory that there are gas hydrates in the sediments beneath the Hudson Canyon Region. Gas hydrates are molecules of methane gas locked in an icy structure. They exist at temperatures near freezing and high pressures within the seafloor sediments. Methane gas is produced from the decomposition of organic materials such as tiny surface plants and animals that settle into the sediments when they die. To assess this area for potential gas hydrates, we are collecting water samples to determine if methane gas is seeping from the seafloor and if so, where this seepage is occurring. If we discover large quantities of methane in the water column, a host of interesting applications and consequences may present themselves.

Niskin bottles on the CTD rosette releasing water from as deep as 3000 meters after samples had been collected. These samples help to determine the presence of methane maxima in the water column. The presence of methane may lead to the discovery of new vent communities and potentially new organisms using methane as a source of "fuel." Click image for larger view.

Dr. Rona described some of the following as reasons for our search for high methane levels in the Hudson Canyon region:

- Similar to hydrothermal vents at seafloor hot springs, methane vents are areas where we may discover new forms of life that add to the biodiversity of our planet. Unlike hydrothermal organisms at seafloor hot springs whose primary source of energy is hydrogen sulfide, these creatures would get their energy from methane gas. Like hydrothermal organisms, the organisms at methane vents may produce natural substances that have medicinal and industrial applications.

- Gas hydrates are potentially a good natural gas energy resource, but recovery of this resource is still a challenge.

- Methane is a greenhouse gas. Release of methane gas from the seafloor could add to the many known land sources of methane that contribute to global warming.

- If the methane gas within the sediments were to become disrupted, it could disturb the overlaying sediments and make them more susceptible to underwater landslides (similar to an avalanche). An event such as this could break the communication cables that lie beneath this Hudson Canyon region. A large enough landslide could displace the overlying water and cause giant waves, called tsunamis. This could have a potential major impact on the coastal zone of the Eastern United States.

Why are we mapping at this high level of intensity?

This mapping project will be one of the few that have been done to this extent and with such highly technical state-of-the-art instrumentation. Our mapping will help us to better understand potential new energy resources and information to better evaluate potential hazards to our climate, shoreline and communications.

What products can we expect from the Hudson Canyon Exploration?

According to Dr. Rona, the scientific team will produce maps and scientific papers that will be available to all and will advance understanding of the resources and hazards of the Hudson Canyon region. The undersea gas may eventually provide the energy to heat and light your home, and knowledge of submarine landslides may be applied to protect your telephone lines and our coastline.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.