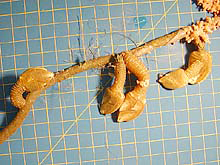

Gooseneck barnacles living on a stalk of dead coral covered with sponge, pink octocoral and bryozoan colonies. Click image for larger view.

Eventful Journeys

July 9, 2002

Catalina Martinez

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

We left the Port of Kodiak the morning of July 4 and weaved our way through the lovely peaks and cliffs that first grabbed our attention only the day before. As the ship made its first turn to leave the Port, three bald eagles passed in front of the bow of the ship, and dozens of puffins could be seen bobbing in the water. Our send-off rivaled our arrival!

We spent the next 15 hours steaming back to Marchand Seamount for the eighth dive of the expedition. The trip was a bit rough, but once on station, the seas died down and allowed for another spectacular dive. Enormous gooseneck barnacles were the unique find of the dive, and several life history stages were present in the samples collected.

We steamed back to Murray Seamount after the dive on Marchand, and completed another successful dive to collect various corals and rocks for later analysis. Once the sub was safely on board, we started the 30-hour steam to our next destination—Scott Seamount. Scott Seamount was listed on the original dive plan as Campbell Seamount, because they are both very close together. When we thoroughly analyzed the charts on board the ship, however, we soon realized that Campbell Seamount and Scott Seamount were separated only by about 30 kilometers. Therefore, we selected the larger of the two (Scott) to explore. Once on station, the scientists and WHOI Engineering Assistant Dave Simms began surveying the area using SeaBeam multibeam sonar, which lasted into the early morning hours.

Dive 10 Lost to Weather

Weather conditions in the Gulf of Alaska are unpredictable at best, and after completing nine successful dives in a row, our luck had finally run out. A low-pressure system brought high winds to the area on July 8, which forced us to abort our dive for the first time during the expedition. Although we were extremely disappointed, we also realized how very fortunate we had been up to this point with weather conditions. SeaBeam surveys continued throughout the day so that the image of Scott Seamount would be complete before the ship moved southeast towards Warwick Seamount. We decided to leave the area and move south, hoping that we would be able to “outrun” the low–pressure system and get at least one dive in at Warwick Seamount before the winds caught up with us.

The updated dive plan includes four consecutive dives at Warwick Seamount at various depths. Hopefully, all four planned dives will occur; Warwick will be the last of five unexplored seamounts visited during this expedition. We hope that the low-pressure system will weaken for the next few days so that when our paths eventually cross, conditions will not force us to abort another dive.

Spider crab missing three limbs on left side, taking a swipe at a rattail fish on Murray Seamount, seen during Alvin dive #3798.

Click image for larger view.

It's a Crab Eat Crab World

Thomas C. Shirley and Zachary Hoyt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

Bradley Stevens and Taylor Heyl

National Marine Fisheries Service, Kodiak

While watching the fascinating views of life on the seamounts, it's easy to forget that one of the basic tenets of natural selection appears to be at work—survival of the fittest. We have noticed that most of the giant spider crabs (Macroregonia macrocheira) viewed from the submersible Alvin are missing limbs. The crabs usually have a black scar (blastema) where a limb once existed, and many crabs are missing more than one limb. These missing limbs are evidence that predation or agonistic interactions (fighting) are occurring on the seamounts. The limbs could be regenerated during molting. But replacing full-size limbs probably requires two or three molts, and very few crabs possess limbs that are partially regenerated.

An adult male spider crab eating a female spider crab on Murray Seamount, seen during Alvin dive #3805.

Click image for larger view.

Why isn't there more evidence of regenerating limbs? One explanation might be that crabs with missing limbs do not live long enough to regenerate limbs. A more likely explanation might be that molting is rare among adult crabs, and we mainly see adult crabs. Perhaps adult spider crabs are similar to many other crabs belonging to the spider crab family Majidae, and cease molting or have very infrequent molting when they become adults. So, the incidence of lost limbs might increase with increasing age. Another clue is that almost all of the limbs are lost at the base of the limb, suggesting voluntary limb loss in response to a stimulus (autotomy). Perhaps once grabbed, the crab releases its limb to escape a grip.

We still do not know the cause of most lost limbs. Most of the fish species that we have observed do not appear to be capable of preying on adult spider crabs. However, more cryptic predators such as octopus, might be responsible. One encounter we experienced presented another prospect—cannibalism. We found an adult male eating a female crab. The tissues present in the female carcass are evidence that he was not simply eating a molt. Also, the male was chewing on a hardened carapace, not a soft molt. In the dark and cold environs of the seamounts, everyone may represent a potential meal!

Gastric mill and teeth within stomach of Grooved Tanner crab (Chionoecetes tanneri), collected during Alvin Dive #3806 on Warwick Seamount.

Click image for larger view.

Eat Now, Chew Later

Maggie Sexton, Undergraduate

Coastal Carolina University

Did you know that crabs chew with their stomachs? When an organism ingests food, it must break that food down into a form that can be converted into energy for the cells in its body. The first step in this process is to mechanically break the food into smaller bits, or to chew it. Many animals have highly specialized systems to perform the task of chewing. Crabs are no exception. They have several specialized mouthparts that help them handle food and direct it into their mouths. But to help with chewing, crabs have teeth in their stomachs. Three sets of teeth make up the gastric mill and are used to grind up food before it is passed on to the rest of the digestive system.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.