Hazardous Implications: Understanding the Tectonic Setting of the Puerto Rico Trench

In 2002 and 2003, NOAA Ocean Exploration supported an expedition to explore the Puerto Rico Trench, which is the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, with water depths exceeding 8,400 meters (5.2 miles). Despite its mysterious origin and the potential tsunami hazard it poses to Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and beyond, the trench had remained largely unstudied. The expedition resulted in several significant discoveries, including a large fault system, similar to the San Andreas Fault in California, in very deep water near the trench. The fault, named after marine geophysicist Elizabeth (Betty) Bunce, interacts with other fault systems to the northeast and northwest of Puerto Rico, producing high rates of seismicity and dramatic topography.

Subsequent expeditions led by NOAA Ocean Exploration to the region have sought to further increase our understanding of the geological setting in the area. Because Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands lie on this active plate boundary, tsunami-causing earthquakes and submarine landslides are potential threats to regional populations, making this understanding all the more important.

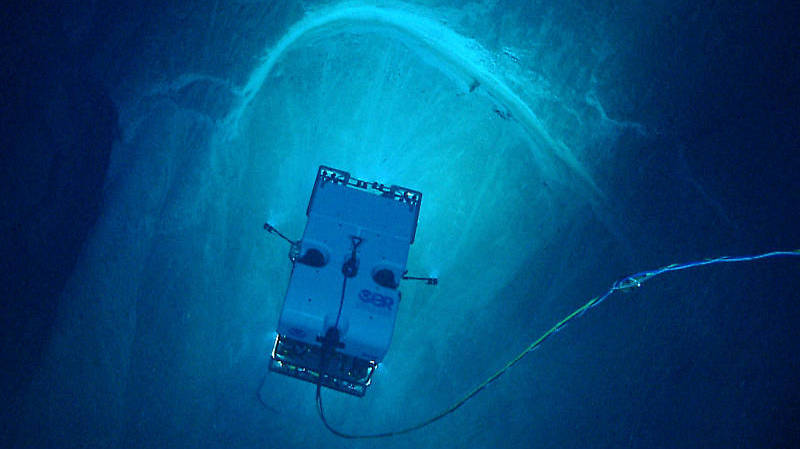

Remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer images a spectacular arcuate, headwall scarp measuring 20 meters (66 feet) across, seen in the carbonate Juana Diaz Formation, Guayanilla Canyon, to the south of Puerto Rico. The image shows that the limestone below the arcuate or curved scarp has broken away and slipped down the slope. Headwall scarps such as this one provide evidence of slope instability in the form of landslides and/or the bare rock faces left behind after a landslide has occurred. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs.

Learn moreAn Explosive Discovery: The First Observation of Active Underwater Volcanic Flows

In May 2009, NOAA Ocean Exploration supported the Northeast Lau Response Cruise, during which the cameras on Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's remotely operated vehicle Jason captured the first-ever observation of active lava flows in the deep ocean at the West Mata volcano, located along the Pacific’s Ring of Fire.

The vast majority of Earth’s crust was formed by submarine volcanoes in the deep ocean, and most of the volcanic eruptions on Earth take place under the ocean’s surface. Observation of the volcanic eruption at West Mata thus marked the first visual documentation of one of the most fundamental processes forming Earth’s surface. Scientists conducted five dives at West Mata during the expedition and observed active eruptions during every dive.

This spectacular sequence provides a close-up view of the eruption at West Mata, with violent magma degassing events producing bright flashes of hot magma. Lava is blown up into the water before settling back to the seafloor and large plugs of lava flow rapidly down the slope. Video courtesy of the National Science Foundation, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and NOAA.

Learn moreOn the Rise: Nearly 600 Methane Seeps Discovered Along U.S. Atlantic Coast

In November 2012, while conducting mapping operations on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer along the U.S. coast from North Carolina to the Canadian border, the NOAA Ocean Exploration mapping team detected deep gas seeps via the ship’s multibeam sonar. At the time, methane bubbles indicating the presence of cold seeps had been detected off the Pacific Northwest, in the Gulf of Mexico, and in parts of the Arctic Ocean, but such seeps were not known to exist along the U.S. Atlantic coast. Subsequent analysis of multibeam data has since revealed that nearly 600 methane plumes exist along the edge of the Atlantic continental shelf, and their presence has been confirmed by multiple visual surveys using remotely operated vehicles. This discovery has shifted our understanding of how methane is transported from the seafloor into the ocean and atmosphere.

During the first-ever deployment of remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer, streams of bubbles were imaged rising from the seafloor off the coast of Virginia. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2013 ROV Shakedown and Field Trials in the U.S. Atlantic Canyons.

Learn moreNot Your Average Flower: “Tar Lilies” Discovered in the Gulf of Mexico

During the Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014, we set out to investigate a target approximately 60 meters (197 feet) long, identified using side-scan sonar and suspected to be a shipwreck. However, within minutes of observing the feature, it became clear that it was not human-made. Instead, the team had found a flower-like extrusion of asphalt on the seafloor.

While a classic conical shape formed by molten rock and spouting glowing streams of lava is what most people think of when they hear the word “volcanic eruption,” eruptions of mud, shale, and salt are also known to form volcanoes. Dubbed the “tar lilies” by scientists, this marked the first known example of asphalt volcanism in this area of the Gulf of Mexico. The discovery expanded the number of known examples of such volcanism around the globe and confirmed the existence of an asphalt ecosystem across the Gulf of Mexico.

Highlights from the Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014 dive to explore the "tar lilies." Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014.

Learn moreTime to Vent: Hydrothermal Vent Sites Discovered in the Mariana Region

Three dives were conducted on the Mariana back-arc during the 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas, resulting in the discovery and documentation of three new hydrothermal vent sites. Scientists observed small amounts of hydrothermal activity at Eifuku Seamount, an entirely new vent field at Chamorro Seamount (an area with no known history of eruptions), and a new active high-temperature “black smoker” vent field composed of multiple chimneys (one over 30 meters (98 feet) tall!) on the Mariana back-arc spreading center.

The Mariana back-arc is a deep rift valley where seafloor spreading is occurring and volcanic eruptions provide the heat to create hydrothermal vents and their unique biological communities.

This incredible active hydrothermal vent was imaged for the first time during the Marianas expedition. It was 30 meters (98 feet) high and gushing high-temperature fluid full of metal particulates. This vent was home to many different species, including Chorocaris shrimp, Munidopsis squat lobsters, Austinograea crabs, limpets, mussels, and snails. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas.

Learn moreSteppe-ing Up: Terraced Features Revealed Off U.S. Southeast Coast

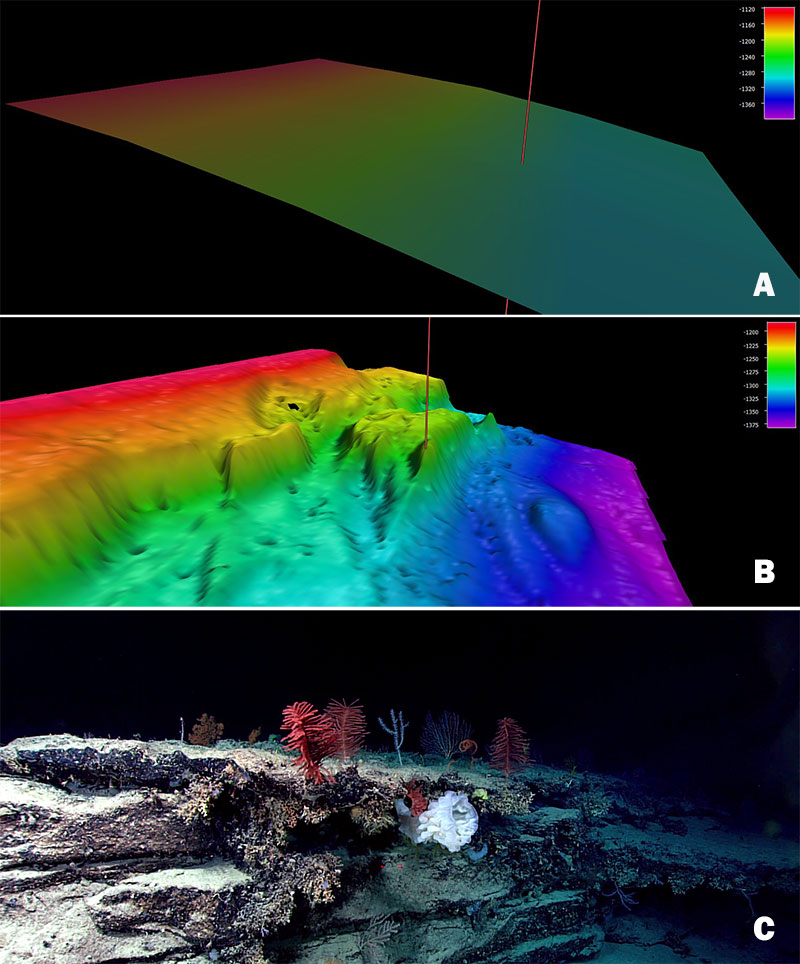

Located off the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, satellite altimetry data suggested that much of the Blake Escarpment had a low gentle slope with no distinct features. However, high-resolution multibeam data collected by NOAA Ocean Exploration changed this understanding in 2018.

During the Windows to the Deep 2018 expedition, multibeam mapping operations conducted by the NOAA Ocean Exploration team via NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer revealed previously unknown bathyal steppe features along the Blake Escarpment. Due to their size, these features cannot be picked up by satellites and can only be seen in higher-resolution multibeam bathymetry. Remotely operated vehicle dives conducted during the expedition showed a highly diverse and dense community of deep-sea corals and sponges on the features, indicating that the features provide important habitat. This discovery illustrates how high-resolution mapping provides us with the foundation needed to fill gaps and build a more complete picture of what lies off our own coast — and it’s not flat and boring.

Image A shows satellite altimetry (Smith and Sandwell, 2014) at the Windows to the Deep 2018 Dive 04 site on “Blake Escarpment South.” Image B shows multibeam bathymetry data collected during the expedition, and Image C shows the coral and sponge community documented via remotely operated vehicle at the site marked with a red line in the mapping data. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Windows to the Deep 2018.

Learn more