Rod Mather, University of Rhode Island Applied History Lab

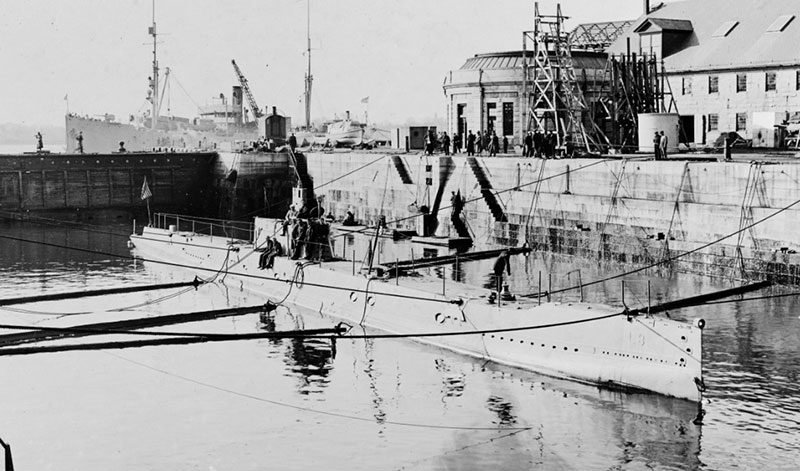

Submarine L-8 in dry dock at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, Kittery, Maine, in 1917. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Download image (jpg, 412 KB).

The submarine USS L-8 claims a notable place in United States and Rhode Island naval history. Launched in April 1917 at Portsmouth Navy Yard, Kittery, Maine, she was the first U.S. submarine to be built in a government yard. The Navy paid the Lake Torpedo Boat Company $52,700 for the plans. The vessel was 165 feet long; 14 feet, 9 inches in the beam; and drew 13 feet, 3 inches draft. She was fitted with four 18-inch torpedo tubes.

The L-8 performed well during sea trials. Its operational history and eventual disposal were deeply connected to the development of underwater warfare at the end of World War I and during the early interwar years.

The United States' entrance into World War I in April 1917 and Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in February that year were interconnected. Now at war, the United States faced a significant threat from German U-boats; a threat for which there were no immediate solutions. One “top-secret” strategy mirrored an approach the British had tried by deploying Q-ships. The concept was to have a decoy merchant ship and a U.S. submarine work in concert. The merchant ship would sail the Atlantic sea lanes as a potential U-boat target; the U.S. submarine served as its escort. If a German U-boat surfaced and attacked the merchant ship with its deck gun, the U.S. submarine would engage the U-boat with torpedoes.

In March 1918, the four-masted lumber schooner Charles Whittemore lost its rudder off Block Island, Rhode Island, and was forced to seek assistance from the U.S. Navy. The Navy requisitioned the Whittemore and fitted her out as a Q-ship. Officials then assigned the submarine N-5 to work in concert with the Whittemore; later they assigned the L-8 to the same role.

In order to respond to a U-boat attack and to ensure that the Whittemore and L-8 remained in contact, the Whittemore towed the L-8 astern. Although no U-boats ever attacked the Whittemore, and the L-8 never fired a shot in anger, the submarine played a highly significant (albeit undisclosed) role in efforts to combat unrestricted submarine warfare during the waning months of World War I.

After the war, the L-8 sailed for San Pedro, California. For the next three years, she served as a platform for Navy experiments and submariner training on the West Coast. The L-8 returned to the East Coast in 1922 and was placed out of commission. The Navy struck her from the Navy List in 1925.

The L-8’s role in Rhode Island’s history of undersea warfare and Navy “top-secret” programs, however, was not over. As the submarine’s service career came to an end, military scientists and engineers at the Newport Torpedo Station were working on a new type of torpedo detonation device, and they needed a test target. Up to this point, torpedoes were detonated using contact exploders. When the torpedo struck an object, it exploded. As a countermeasure, some warships were being fitted with thicker armor, torpedo belts, and/or torpedo blasters. These countermeasures meant that by the early 1920s, the U.S. Navy became convinced that contact torpedoes were becoming obsolete, particularly for attacks on battleships. One solution was to detonate the torpedo underneath an enemy vessel – triggered by magnetic influence rather than contact. If the exposed and vulnerable ship’s keel could be broken by the compression of an underwater explosion, the ship would likely founder.

“Project G-53,” based at Newport, to develop a magnetic influence exploder, was one of the most secret Navy research and development programs ever undertaken. By May 1926, Navy scientists had made significant progress. Now they needed a test target, and the L-8 fit the requirements. On May 26, 1926, the submarine was anchored at the entrance to Narragansett Bay. A magnetic influence exploder was fitted to a Mark 10 torpedo and then fired at the submarine. The torpedo ran directly under the L-8, but did not explode. A second test firing proved successful and the L-8 sank to the ocean floor. Those two firings were the only live tests of the magnetic influence exploder before World War II.

The L-8 remained generally undisturbed on the seafloor until the late 1980s and early 1990s when CONUSUB, an Aquidneck Island-based commercial diving company owned by Stephen Moy, started to work the wreck. In 1989, the company recovered one of the propellers, which they later passed on to the Naval War College.

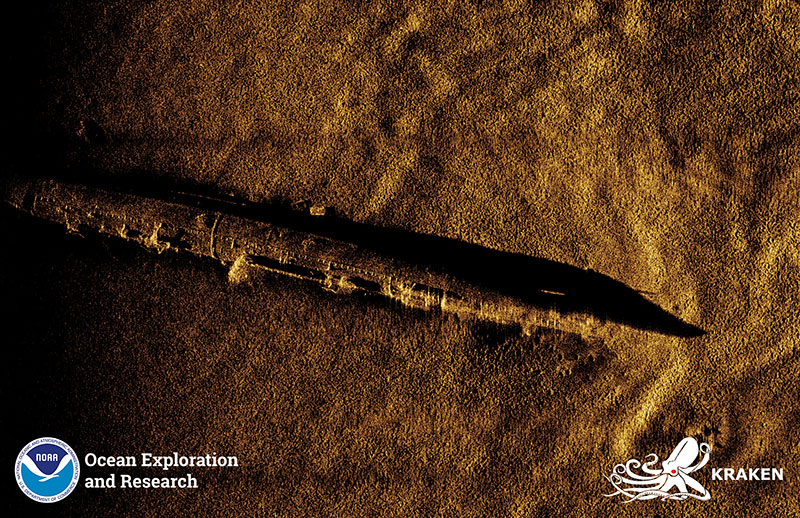

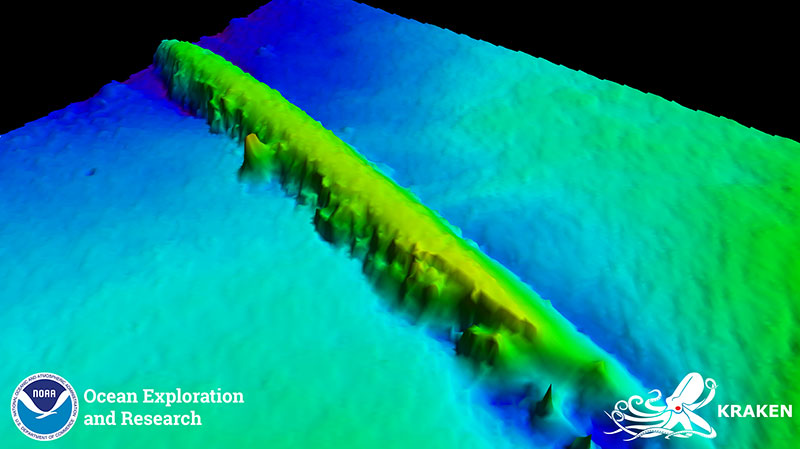

Synthetic Aperture Sonar imagery of the USS L-8, developed using data collected using the KATFISH™ system. The submarine is largely intact and appears to be resting on its port side. Sections of the outer hull are missing, likely caused when the vessels propellers were removed in the late 1980s. Image courtesy of Kraken Robotics. Download image (jpg, 4.6 MB).

High-resolution mapping of the L-8 using Synthetic Aperture Sonar on Kraken Robotics' KATFISH™ system demonstrates that the submarine is largely intact and that the hull itself retains some archaeological integrity. The L-8 appears to be resting on her port side in about 110 feet of water in an east/west orientation. Sections of the outer hull are missing, the pressure hull has been breached, and there is some damage to the stern – all likely exacerbated by attempts to salvage the vessel's propellers in the late 1980s.

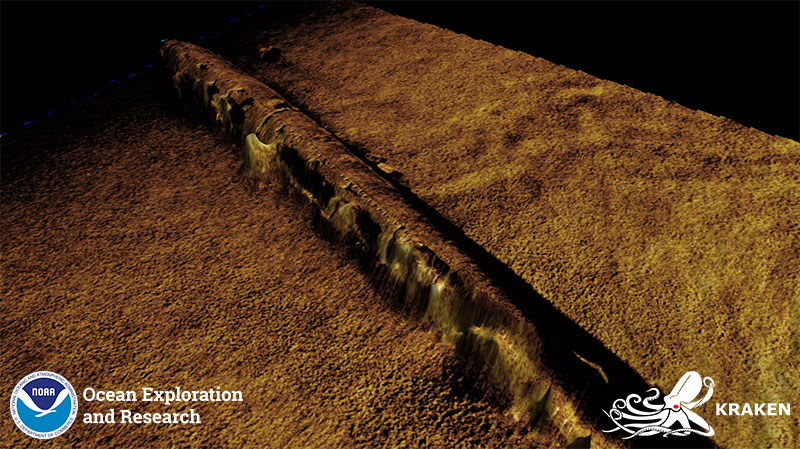

Three-dimensional Synthetic Aperture Sonar image of the USS L-8 submarine, developed from data collected using the KATFISH™ system. Image courtesy of Kraken Robotics. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

Three-dimensional bathymetric image of the USS L-8 submarine, developed from data collected using the KATFISH™ system. Image courtesy of Kraken Robotics. Download map (jpg, 727 KB).