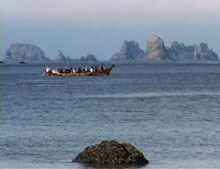

The Olympic Coast, home of the Makah, Quileute, Hoh and Quinault nations and Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, represents some of the most pristine coastline in the lower 48 states. (Photo: Robert Steelquist, OCNMS)

The Sanctuary is the Water

that Carries the Canoe

By Robert Steelquist

Education Coordinator

Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary

Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary is first and foremost a place. It encompasses 3,310 square miles along Washington’s rugged coast. Along much of its 135-mile extent, it hasn’t changed very much since Europeans first visited in the 18th Century or since ancestors of Native Americans lived here for countless generations before. There are trees still alive that witnessed the entire parade of events that we call history—and what came before that. After thousands of years, their shadows still darken the water that laps against these shores.

The significance of place in our lives is profound. After all, only places contain the ecological systems that sustain life. Life as an idea is meaningless except in places. Places and the forces that swirl through them shaped our genes and those of every species. Places form the context of all our experiences and have nourished every culture in indelible ways. We are rooted in places, however transitory our lives can seem. We are always somewhere.

Against the sublime beauty of Quillayute Needles, Lee-Cho-Eese follows the ocean trails of generations of ancestors. (Photo: Robert Steelquist, OCNMS)

Our planet—as a system of places—has been transformed by human presence and the effects of human action. We shape our surroundings by our mere being. And that shaping has taken enough of a toll that we now protect certain places—like Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary—from further harm. In the process of protecting these places, we take account of their unique qualities, the animals and plants they support, the historic and prehistoric remains they contain, their air and water, their scenery, their stories and songs. We call those qualities “resources,” and we pass laws like the Marine Sanctuaries Act to conserve those resources.

The places become parks, refuges, sanctuaries, wilderness areas, memorials, shrines, monuments or any other name that recognizes their uniqueness or perpetual value to our larger society. For those who “manage” such places, the task at hand is nothing less than the responsibility to transfer those qualities—undiminished—to the generations that follow including those, as yet, unborn.

The canoe tradition is itself a means of transport—of people moving together through time. Connected to the places signified in the songs and experiences of ancestors and elders, the young inherit their culture and discover their own place in the world and the future. (Photo: Robert Steelquist, OCNMS)

As ambitious as that goal is, the Western scientific tradition approach to protecting places is limited. We define timeless values around “resources” as though they are discrete treasures in a box. We “manage” them as though cause and effect of harm and protection are mechanical processes. And though “we” are charged to represent the values of all Americans, our approach is distinctly one of rationalism, in which scientific and economic methods and values trump all others, including those reflecting the perspectives of Native Americans—the original people of these places.

Yet important places like marine sanctuaries possess inherent value—defined in other terms—for Native Americans. Here, generations of ancestors lived, the rhythms of their lives intertwined with the rhythms of the workings of the planet. Ecological knowledge abounded, places were mapped in story and song, time sequences recorded in the oral tradition. Features on the land and in the sea were named and known. Social organization, laws, language, patterns of daily life all formed in direct relation to place. Dimensions of experience that Western science cannot account for—spirituality, creation, mysterious forces in the world—were encoded as meanings, associations and values for places.

Through centuries of difficult times, Native people have carried a view of these places forward and have sought to connect new generations of youth with those places and their legacy, their twin birthrights. Against tremendous odds, the languages, stories, songs and daily practices have persisted in spite of organized—sometimes legislated—attempts to end them. Tenuously some of these traditions have survived.

Today, there are many revivals underway among Native Americans. One of these is the revival of the Canoe Culture, still found in places where it was born. Each year, Northwest tribes reaffirm a powerful relationship with the ocean. From Vancouver Island, Georgia Strait, Puget Sound, Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Olympic Coast canoe teams travel to old villages and reconnect the threads of their relationship to place.

The crew of the Quileute canoe Os-Chuck-A-Bick sings as it approaches the ancient village site of Ozette. The rugged seastacks of Point of Arches form the backdrop. (Photo: Robert Steelquist, OCNMS)

It is natural that they visit wild places. It is in the shadows of the wild that the old forces are still at work. It is among the community of animals and plants, among the winds and fogs that the primal forces of place still reside. Here too, remain standing trees that are hundreds of years old, rocks and seastacks that have endured thousands of winter storms, inspired songs and stories and formed the object lessons for youth for scores of generations.

Without wild places, cultures wither and die. Like a canoe out of water, such a culture dries and cracks. It may retain its graceful appearance and artful decoration, but it loses its vital function of giving identity to people and heralding their home. We need places—sanctuaries—for cultures.

It was this imperative that led foresters Aldo Leopold and Bob Marshall to promote the value of wilderness areas as necessary landscapes in a changing and otherwise changed world. True to their own social and cultural values, they understood that the historical experience of Americans was played out in a backdrop of the wild.

The one-on-one encounter with wilderness forged our spirit, our national identity. And no less than for generations of increasingly urban Americans, Native Americans and First Nations also need sanctuaries—places where their heritages were formed, long before Europeans first encountered the wilds of North America. Places where, in the experience of new generations, their own spirits can be forged, their identities can be discovered and celebrated.

As it has since time began, sunlight bathes the waters. For thousands of years, the silhouettes of the canoe and its pullers has crossed this sea- and landscape. The Canoe Culture thrives. (Photo: Robert Steelquist, OCNMS)

The renewal of the Canoe Culture reaches deepest into the identities of its seekers in wild and untrammeled places. Here, the acts of pulling against the ocean and pulling together as a crew reach their highest levels of achievement. In awe and wonderment of the raw and forceful ocean, undistracted by concrete shores or polluted water, the inner forces arise, the old songs echo unbidden and the Ancestors emerge from the shadows to slip into the canoe and take their places alongside the pullers and join the journey. This is where the Canoe Culture and the Ocean meet on their own, respective terms.

Places like Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary are necessary reminders of who we are—Native American and otherwise. And without these places, we are all diminished people, uprooted and restless. Our need for these places is shared. Though our understandings and values for them may be different, our claim to them is as a single people. We celebrate, together, this place’s many dimensions—its living forms, its wildness and its meanings—immeasurable and various.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.