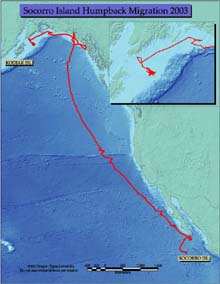

The whale shown on the map was tracked for a total of 7,745 km (4,813 miles) as it traveled from Socorro Island, where it was initially tagged, up to Vancouver Island. Note that this animal stuck relatively close to shore during its migration, though it was still well past the continental shelf for most of the journey. Click image for larger view.

Marine Nekton as Ocean Explorers

Summary

A growing body of evidence suggests that most marine nekton (free swimming animals) have well-defined migration behaviors in the sea, potentially defined by specific physical features or, alternatively, migration corridors that are fixed in space. However, many marine animals using the open ocean, e.g. North Pacific humpback whales, undertake large-scale migrations that are poorly understood.

Oregon State University (OSU) scientists have been using cutting-edge technology—in the form of electronic tags monitored by satellite—to study migration routes and patterns of humpback whales tagged off Hawaii. Analyses reveal that, instead of swimming straight from Hawaii to Southeast Alaska and British Columbia, these animals fan out across the North Pacific. Some head straight for the well-known summering areas in Southeast Alaska and British Columbia. Others travel due north to the Aleutian Chain. One animal in particular arrived at the Chain, turned left and continued all the way to Kamchatka, Russia. This was the first time anyone knew that Hawaiian humpbacks did not simply go from Point A to Point B, but instead use the entire North Pacific basin.

Aside from the Hawaii study, no other satellite studies had been done on North Pacific humpback whales, until recently. In February 2003, Dr. Bruce Mate and his research team from Oregon State University traveled to Socorro Island, Mexico in search of humpback whales. There are three known humpback reproductive populations in Mexico: one off the coast of mainland Mexico, one off the tip of Baja California Sur, and a third around the Revillagigedo Archipelago (a set of four islands, Socorro being the largest). The first two populations are better studied than the third, and many of the animals from these areas have been characterized as feeding off Oregon and California during the summer feeding season. A percentage of these animals go to unknown locations, however—and in photographic identification studies, no link has been found between these two populations and Socorro Island. The summering areas of the Socorro Island humpbacks had been unknown until this study.

Oregon State University's Dr. Bruce Mate and two research assistants aboard the HMSC Beagle, one of the inflatable boats used for whale tagging off Oregon and California. Click image for larger view.

After successfully tagging 11 humpback with radio-monitored satellite tags off Socorro Island, Dr. Mate and his team returned to their Oregon lab to watch the results as the tags transmitted location data to overhead satellites. The data have revealed three important findings:

1) Some of the tagged whales visited Bahía Banderas (mainland Mexico) and the waters off Cabo San Lucas (Baja California Sur), linking Socorro Island whales to the other two reproducing populations for the first time.

2) As the whales moved north for their spring migration to summer feeding areas, they have remained offshore. The closest any whale came to the Oregon coast was 30 miles; others ranged up to 600 miles offshore. This means that these animals are unlikely to be photographed in route, making photo identification difficult to impossible.

3) When the whales arrived at their summer feeding destinations, they were still too far offshore for coast-oriented researchers to photograph them. It’s well known that some humpbacks wintering off the Hawaiian Islands migrate to British Columbia and Southeast Alaska for the summer, but until now it was not known that some animals from the Socorro Island population go to the same places.

These maps illustrate the northward migration and probable feeding movements of two humpback whales tagged with satellite-monitored radio tags. The whale shown on the first map was tracked for a total of 7,745 km (4,813 miles) as it traveled from Socorro Island, where it was initially tagged, up to Vancouver Island. Note that this animal stuck relatively close to shore during its migration, though it was still well past the continental shelf for most of the journey. The inset map shows a more detailed image of the whale's movements near Vancouver Island. The whale's trackline was fairly direct until it arrived at Vancouver Island, at which point it began demonstrating the shorter tracklines usually associated with feeding movements.

TThis map shows a tagged whale moving from Socorro Island to the southern tip of Baja California Sur, Mexico, before migrating north to Alaska in a trip totalling 10,562 km (6,563 miles). This whale traveled much further offshore (by several hundred miles) than the first whale. Click image for larger view.

The second map shows a tagged whale moving from Socorro Island to the southern tip of Baja California Sur, Mexico, before migrating north to Alaska in a trip totalling 10,562 km (6,563 miles). This whale traveled much further offshore (by several hundred miles) than the first whale. It came nowhere near Vancouver Island, instead moving up to northern British Columbia and along the Alaskan coastline. The inset map shows the whale making typical feeding movements in an area northeast of Kodiak Island.

Both of these maps demonstrate that at least some Socorro Island whales summer in the same areas that Hawaiian Island humpbacks are known to frequent, marking the first time this association has been proven. The second map also demonstrates an association between the Socorro Island and the Baja California populations -- the first time this has been proven, as well.

This study, made possible by funding from NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration, represents the first time that Socorro Island humpbacks have been definitively tracked from their reproductive area and the first time that their summer feeding destinations have been identified. Several tags are still transmitting four months after placement, and the continued data will add details to our knowledge of the whales’ summer range and feeding habitats. These feeding habitats, in addition to the places where whales go to breed and calve in the winter, are defined as “critical habitats” because they are the areas most critical to a whale population’s survival and recovery. Critical habitats are unknown for many populations of whales; our ability to make wise marine management decisions that could aid (or at least not hinder) the recovery of whales depends in part on identifying places such as that which we are learning about with the Socorro Island population.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.