by Carolyn Ruppel, U.S. Geological Survey, Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Adam Skarke, Department of Geosciences, Mississippi State University

Shannon Hoy, Cherokee Nation Strategic Programs at NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

July 7, 2019

Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download larger version (mp4, 90.4 MB).

During Dive 14 of the Windows to the Deep 2019 expedition, NOAA’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Deep Discoverer, also known as D2, explored cold seeps arrayed along a ridge located about 62 kilometers (39 miles) offshore Bodie Island, North Carolina. These methane seeps had never before been visited by autonomous, remotely operated, or human-occupied vehicles, and scientists were excited to watch as D2 made new discoveries during its progress up the ridge.

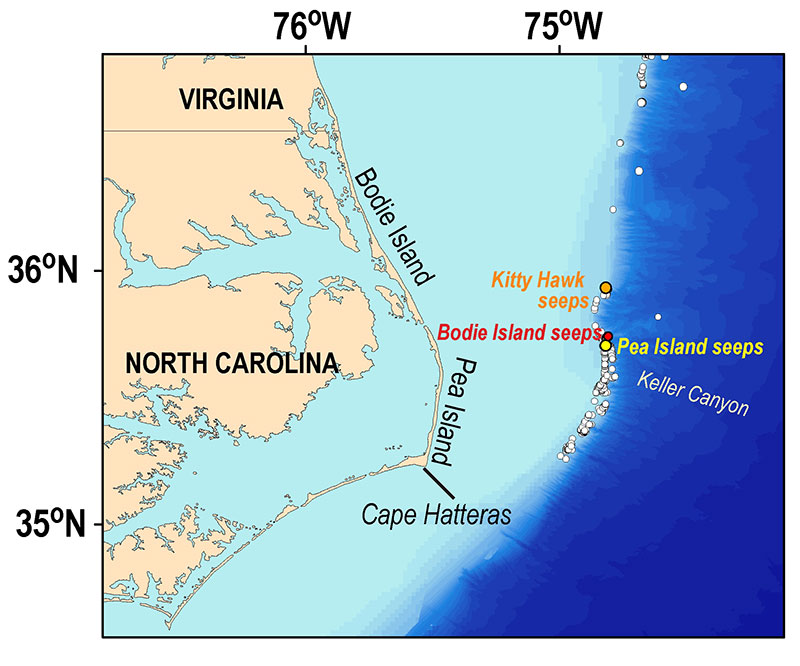

Location of Bodie Island seeps offshore Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, shown relative to the Pea Island and Kitty Hawk seep fields which were explored in April 2019 as part of the DEEP SEARCH 2019 expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

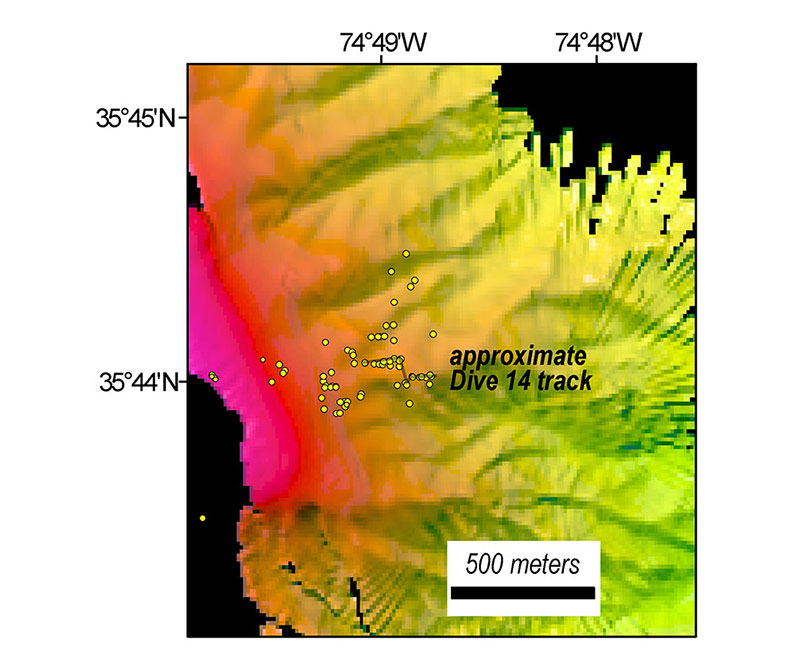

New bathymetric data acquired by NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer with the location of methane seeps identified since 2012 shown as yellow circles. The dive track covered about 55 meters (180 feet) along the ridgeline. Pink shading at the left side of the map is approximately 150-180 meters (490-590 feet) water depth. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

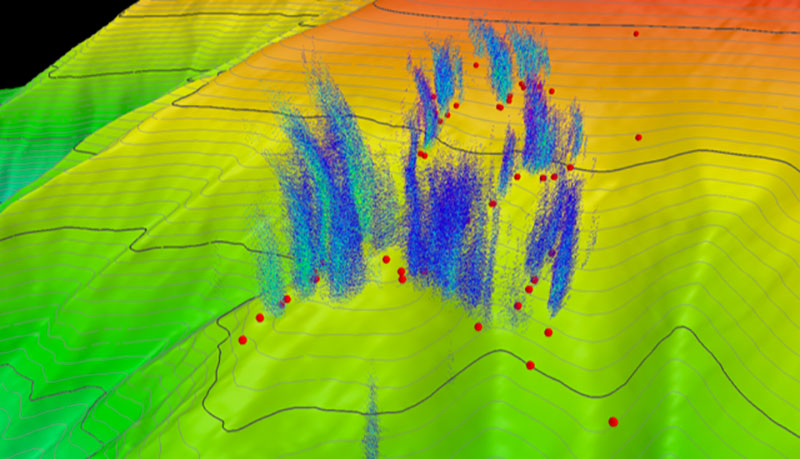

Like the hundreds of other methane seeps identified on the U.S. Atlantic margin since 2012, the Bodie Island seep field was first discovered based on the analysis of water column acoustic images that revealed gas bubbles rising in plumes above the site. Researchers from Mississippi State University used NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer multibeam sonar data collected in 2012 and 2014 to map a line of methane plumes emanating from near the spine of a ridge, at roughly 415-360 meters (1,362-1,181 feet) water depth. In 2017, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) mapped some of the same plumes and located a few more in the larger seep field using an EK80 fisheries sonar and a different multibeam system. Although the Bodie Island seep field plumes had been mapped several times over the past few years, it was not until the Okeanos Explorer collected new water column data in the days before the Windows to the Deep 2019 dive that researchers were reassured that the seeps were still active.

Upslope three-dimensional view of the Bodie Island seeps, with the upper slope bathymetry contoured at 10 meters (~39 feet). Bathymetry is shown with vertical exaggeration. Blue and green clouds in the water column were imaged by the Okeanos Explorer’s multibeam sonar and represent acoustic returns from ascending bubbles associated with methane plumes generated at seafloor gas seeps. The red circles on the seafloor are seep locations identified from previous water column imaging. Note that not every previously identified seep was associated with a methane plume during the current Okeanos Explorer expedition. Data collected by the Okeanos Explorer and processed by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, with image rendering by A. Skarke. Download larger version (jpg, 298 KB).

As D2 neared the seafloor, a high density of shrimp, squid, and fish was encountered in the water column, similar to observations at some other canyon heads and seep sites on the margin. Over the next few hours, the ROV climbed up the ridge from the landing site through waypoints chosen to coincide with the base of methane plumes and areas of high seafloor reflectivity for sonar signals.

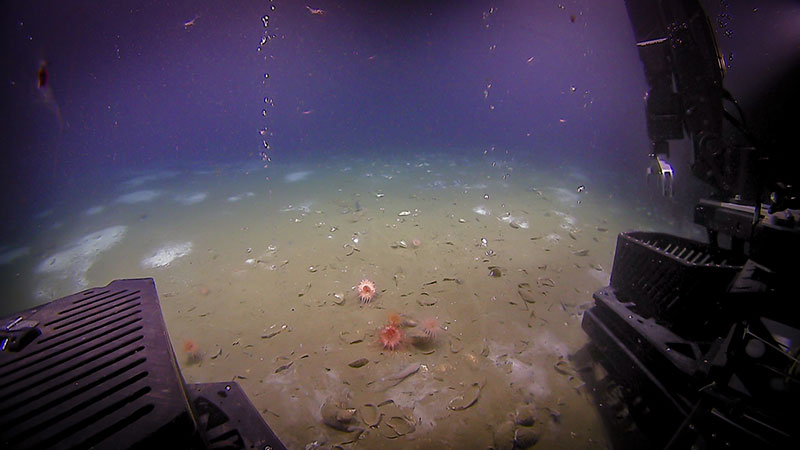

Along the easternmost part of the route, D2 encountered methane bubbles escaping from the seafloor, mats of filamentous bacteria (Beggiatoa), Bathymodiolus mussels, and special carbonate rocks produced as a byproduct of bacterial methane consumption. This is the first time chemosynthetic mussels have been found at a cold seep site between the Norfolk Canyon deepwater (~1,400 meters/4,593 feet) seeps offshore Virginia and the Blake Ridge diapir deep seep (~2,100 meters/6,890 feet) offshore South Carolina. In some locations, numerous bubble streams emerged from the seafloor in a small area, with some seeps continuous and others turning on and off over periods of less than a minute. Bubble streams concentrated in a small area contribute to forming a single gas plume in the water column.

Bathymodiolus mussels and white bacterial mat on dramatic relief created by authigenic carbonate boulders at one of the seep sites explored during the Bodie Island dive. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

In some places within the Bodie Island seep field, the mussels and bacterial mats had a patchy distribution that may reflect spatial variations in the supply of methane and/or hydrogen sulfide beneath the seafloor. D2 also discovered areas of dense, live mussels and large mats, as well as bacterial mats enveloping live mussels. Spider crabs, quill worms, sea stars, anemones, and several fish species were frequently observed along the dive track. At the southernmost seep, large carbonate boulders were observed with attached Lophelia corals, with one colony measuring over a meter wide.

Colonies of the stony coral, Lophelia pertusa, clinging to carbonate boulders a few meters from the mussel beds shown in the previous image. The colony in the foreground is over a meter (~39 inches) wide. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

The Bodie Island seep field is approximately 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) north and about 100-150 meters (328-492 feet) deeper than the Pea Island seeps investigated during the spring DEEP SEARCH 2019 expedition sponsored by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, NOAA, and the USGS. The Pea Island seeps and the Kitty Hawk seeps approximately 19 kilometers (12 miles) north of the Bodie Island seeps were the locations of the first discoveries of vestimentiferan tubeworms on the U.S. Atlantic margin. These tubeworms derive energy from hydrogen sulfide and had previously been found at cold seeps in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. D2’s brief exploration of the Bodie Island seeps did not discover any tubeworms. Conversely, no Bathymodiolus mussels were found at either Pea Island or Kitty Hawk seeps.

The westernmost, upslope part of the Bodie Island seeps dive traversed the base of other large plumes imaged during the Okeanos Explorer pre-dive acoustic surveys. The methane seeps supplying these plumes did not have well-developed chemosynthetic communities or associated carbonate rock, and the bubbles were observed emanating from mostly bare seafloor with small surrounding bacterial mats. Notably, these seeps lie on the northern side of the ridge, whereas the seeps at the easternmost part of the dive, where carbonate and chemosynthetic organisms were abundant, were observed on the southern side of the ridge. The reason for such a stark contrast between seep environments that are in such close proximity is not known, but could reflect the influence of regional currents, which mostly impinge on the ridge from the south.

Two bubble streams emanating from relatively bare seafloor and framed by D2 during the Bodie Island seeps dive. Note patchy distribution of white Beggiatoa bacterial mats in the background and Bathymodiolus shell debris and live mussels in the foreground, along with anemones. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download larger version (jpg, 973 KB).