by Nick Pawlenko, LT/NOAA, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

April 15, 2018

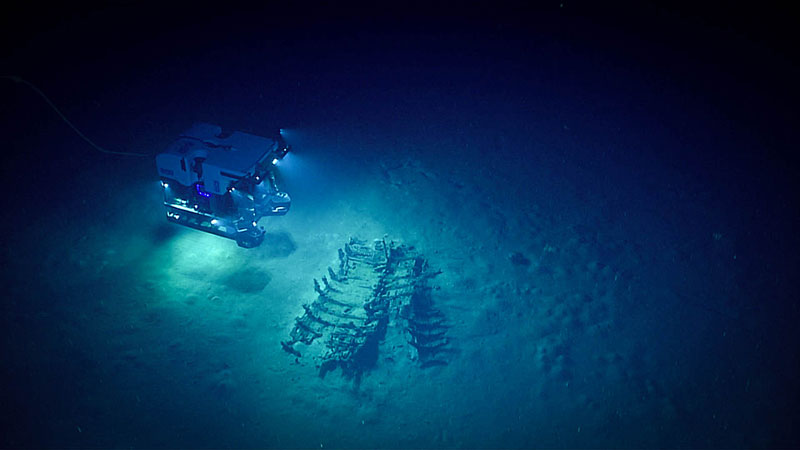

ROV Deep Discoverer explores the cultural heritage site during Dive 02 of the Gulf of Mexico 2018 expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 311 KB).

While organizing the Gulf of Mexico 2018 expedition, we had several planning calls led by Frank Cantelas, Director of NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program, with marine archaeologists from all over the country to discuss possible dives. As a group, these archaeologists evaluated and prioritized possible marine cultural heritage sites in the Gulf of Mexico that have never been explored. From this list of priorities, we developed a dive plan for the entire expedition in the hopes that we would be able to visit one or two of these sites during the expedition. We wanted to increase the number of cultural heritage dives and also meet our overall science objectives for the expedition. NOAA works hard to balance the needs of the entire science community in every region we operate in.

As part of our NOAA science and engineering objectives for this expedition, we planned for two engineering dives to shakedown remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Deep Discoverer in both shallow and deep water. We strategically planned these engineering shakedown dives near cultural heritage sites, in case we got ahead of schedule and had time to visit shipwrecks as well. We thought this would be a good way to increase morale on the ship and still meet our objectives.

The shakedown dives needed to be the first two dives of the expedition and they had to be in striking distance from leaving port. NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer travels about 8-10 knots per hour, traveling about 200 nautical miles in a day without an ROV dive and around 100 nautical miles if we are stationary for half the day during an ROV dive.

In addition, the first dive site needed to be in water less than 800 meters (2,625 feet) and the second needed to be in water greater than 1,000 meters (3,280 feet). This did not leave many options from my list of priorities developed by the archaeologists. It left me with a shallow site for the first day and a second site less than two nautical miles from a semi-submersible oil rig. I felt really good about the location for Dive 01, but was very concerned about the location of Dive 02. This was my first experience with a semi-submersible oil rig (see below for more information).

ROV Deep Discoverer (D2) was placed in the water right away, and the team started working on their engineering shakedown objectives. The team diligently tested their hydraulic systems, buoyancy systems, camera systems, thrusters, manipulator arms, video, and navigation systems. We setup an archaeological call with our team onshore for 11:00 AM ship time, just in case things were looking good. Morale was high as each system passed the test.

At 11:00 AM we began discussing the possible cultural heritage dive as the Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration (GFOE) Dive Supervisor, Karl McLetchie, checked in with his team. Right before the archaeological call ended, he passed us a note that said, “set the table for 12:15.” The control room was filled with excitement as we announced the news to the shore side team—we knew that we were headed to an unknown shipwreck!

Port side of what is believed to be the tugboat New Hope, which was sunk during Tropical Storm Debbie in September 1965. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 668 KB).

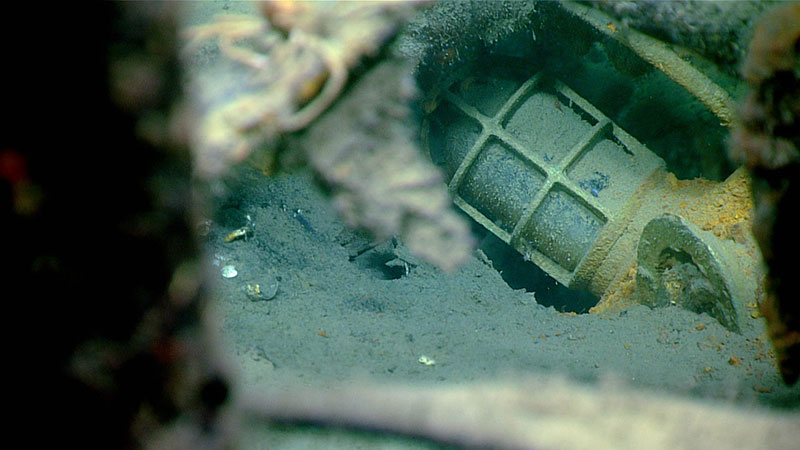

An electric light fixture was observed on the wreck surveyed during Dive 01 of the Gulf of Mexico 2018 expedition. The metal cage surrounding the light fixture is meant to protect it from damage, as the heavy work activities on boats make fixtures such as lights susceptible to breakage. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download map (jpg, 486 KB).

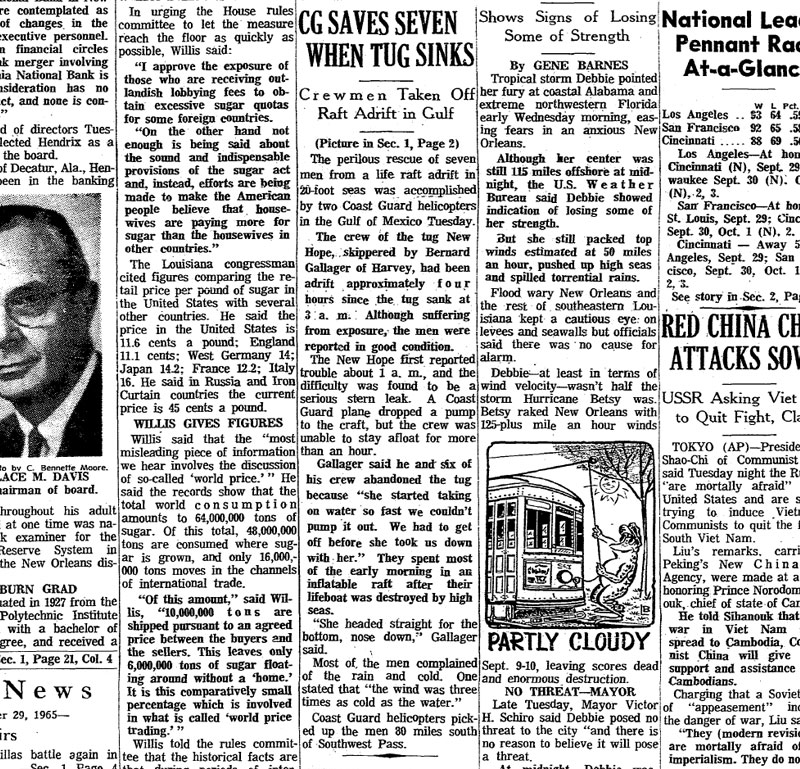

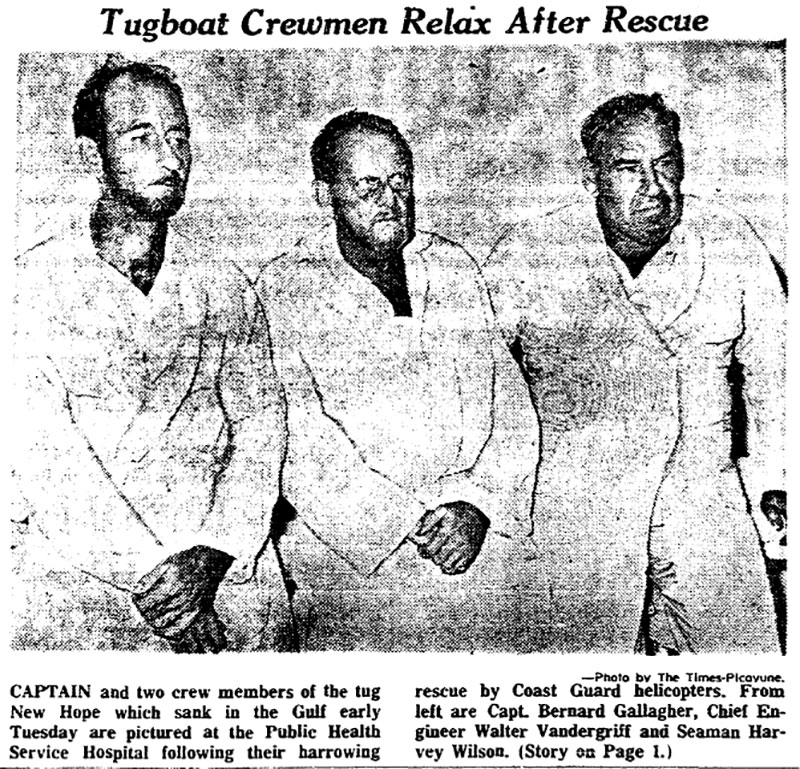

Right at 12:15 PM, the ROV navigator picked up the target in his sonar and we were beginning to see what looked like a thick cable stretched out along the ocean floor. We followed the cable toward our target and, in the distance, a shipwreck emerged, confirming the archaeologists’ suspicions that this was in fact tug boat New Hope, which was lost at sea during Tropical Storm Debbie in 20-foot seas in 1965. We later learned that all seven sailors on the tug were recovered by a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter after more than four hours adrift in a life raft.

An article about the U.S. Coast Guard rescue of the crew of tugboat New Hope appeared in the September 29, 1965, edition of the Times-Picayune. Credit: The Times-Picayune. Download article (pdf, 819 KB).

Image of the captain and two crew members of tugboat New Hope in the September 29, 1965, edition of the Times-Picayune. Credit: The Times-Picayune. Download article (pdf, 871 KB).

After a great first dive, I was excited to see if the strategic plan would pay off a second time. For planning, I reached out to our partner Jack Irion at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Managment. Jack was able to get us permission to dive near the semi-submersible oil rig and was also able to get us diagrams of the moorings used to anchor the rig with the mooring locations. I am not sure this dive would have happened without his help.

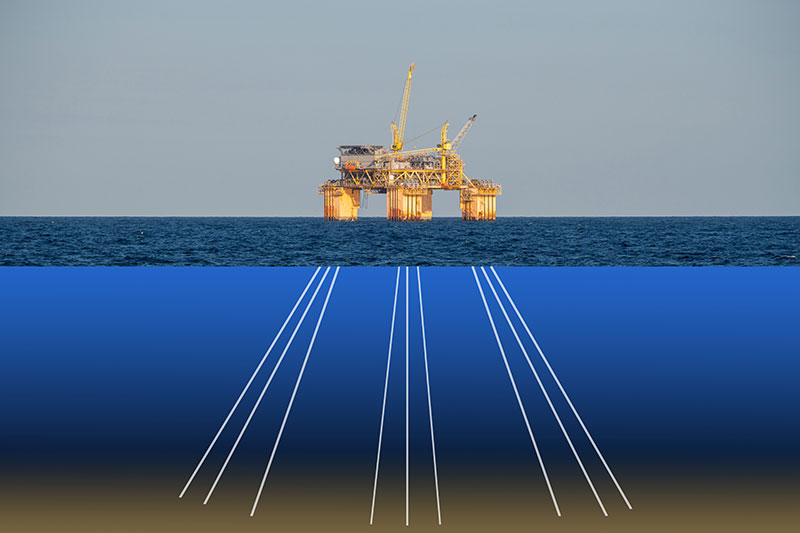

I also learned that a semi-submersible oil rig is a floating platform that is anchored to the ocean floor with strong mooring lines. These lines can extend many nautical miles out in some cases. This is a real concern for an ROV that is tethered to the ship. The last thing we want to do is tangle D2 in these mooring lines.

A semi-submersible oil rig is a floating platform anchored to ocean floor with strong mooring lines that can extend many nautical miles out. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE Download larger version (jpg, 5.7 mB).

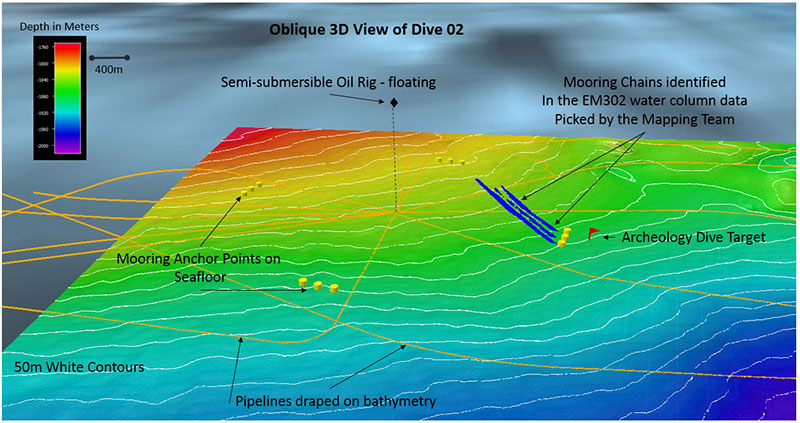

We had many meetings with the Okeanos Explorer Commanding Officer Eric Johnson, ROV Dive Supervisor Karl McLetchie, and Mapping Lead Mike White to discuss the logistics for the dive. Mike worked hard to input the mooring lines into his GIS layers, while Karl looked at the mooring lines in close proximity to the dive site. The mapping team was also able to map the area overnight and the team was able to locate the rig’s mooring lines with ship’s multibeam sonars! Also we all looked currents and winds for the day, as we did not want to be pushed toward the mooring lines if there was an issue.

Bathymetric image of the semi-submersible oil rig, its mooring anchor points, its mooring chains (identified by the mapping team in the water column data), pipelines, and the marine archaeological dive target. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 565 KB).

The plan paid off a second time, our partners at GFOE were able to meet their engineering objectives and we were able to visit the second cultural heritage Site in two days! We were also able to witness an epic Muusoctopus battle for den space on the second wreck.

Two Muusoctopus spp. appear to wrestle for space inside the wreck seen on Dive 02 of the expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 835 KB).