By Dr. Carolyn Ruppel, Research Geophysicist, U.S. Geological Survey

Dr. Diva Amon, Research Fellow, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom

December 20, 2017

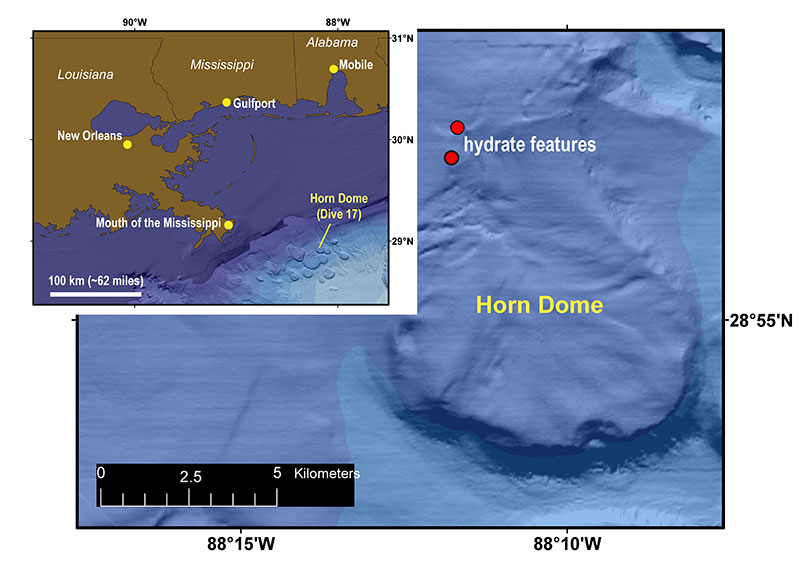

Dive 17 explored the northwest part of Horn Dome, a salt-cored bathymetric high that had been the focus of several previous remotely operated vehicle dives. Seafloor outcrops of gas hydrate were found at several locations during the dive. Bathymetric data and shaded relief from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s dataset. Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey. Download larger version (jpg, 4.9 MB).

NOAA’s Deep Discoverer (D2) remotely operated vehicle (ROV) encountered gas hydrate mounds, ice worms, chemosynthetic communities, and active gas seeps during Dive 17 of the Okeanos Explorer Gulf of Mexico 2017 expedition. Guided by seafloor anomalies delineated by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and by Okeanos sonar data that had detected plumes of gas bubbles in the water column, Dive 17 explored the seafloor at ~1,050 meters water depth (3,445 feet) on the northwestern edge of a salt-cored Horne Dome, ~87 kilometers (54 miles) from the Mouth of the Mississippi, Louisiana.

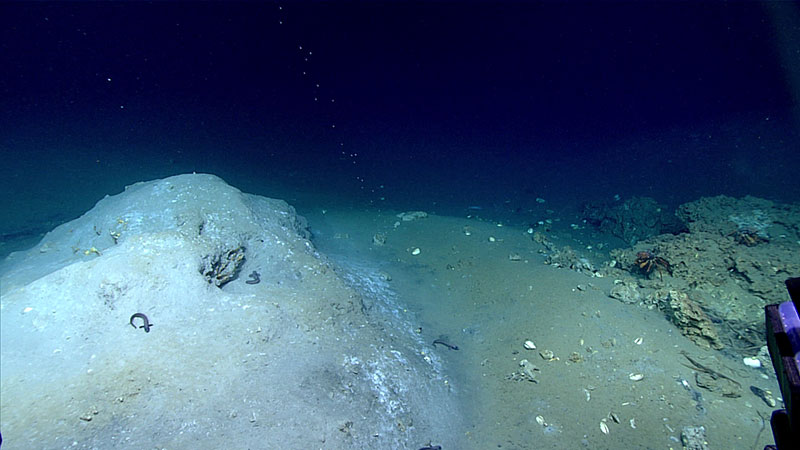

During the dive, D2 discovered low relief seafloor mounds that mantled gas hydrate deposits interspersed with carbonates. Gas hydrate forms when low molecular weight gas (usually methane) combines with water and freezes to form “methane ice” under low temperature and moderate pressure conditions. In the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, the ample supply of gas, coupled with appropriate pressure and temperature conditions, cause gas hydrate to form on or just beneath the seafloor, a phenomenon first described ~25 years ago.

During several dives on the Okeanos Explorer Gulf of Mexico 2017 expedition, we found low relief, sediment-covered mounds that may contain a core of gas hydrate mixed with sediment and carbonate rock. The mounds probably form as the underlying gas supply builds up a hydrate deposit beneath and on the seafloor. This mound found during Dive 17 has exposed hydrate just below the peak and a bubble stream visible in the center of the photo. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 889 KB).

During Dive 17, scientists observed dense orange-stained gas hydrate exposed in several mounds. In some places, the same outcrop had both massive gas hydrate that had probably formed below the seafloor and clear, porous gas hydrate made up of hydrate-encased bubbles. Video recording of methane emissions adjacent to one of the massive hydrate deposits provided insights into seafloor gas dynamics. For example, rapid gas emissions produced bubbles, with some bubbles emerging from clear tubes formed from gas hydrate. Slow gas emissions led to the formation of hydrate-coated gas droplets that initially blocked the gas conduit until the pressure inside the droplet increased, causing the droplet to detach. Similar phenomena were filmed on bare seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico during a 2014 Okeanos Explorer expedition.

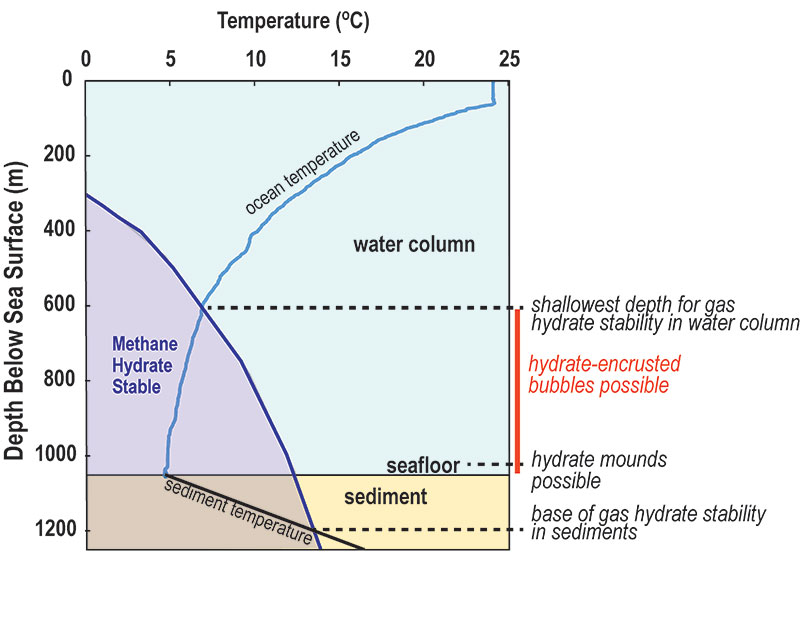

Methane hydrate is stable to the left of the purple curve on this temperature-depth plot. Each 100-meter (~328-foot) increase in water depth corresponds to a pressure increase of ~10 megapascals (~98 atmospheres). The blue curve shows the ocean temperatures measured by the conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) sensor on the Deep Discoverer ROV during Dive 17 at Horn Dome. The sediment temperatures are estimated based on a study that examined nearby well data. Gas hydrate is stable at the seafloor, in the shallow sediments, and from the seafloor to ~600 meters depth in the water column. Such conditions are typical for the deep ocean, but the Gulf of Mexico leaks such large volumes of gas that near-seafloor gas hydrate is more common there than in most locations. Diagram provided by C. Ruppel, U.S. Geological Survey. Download larger version (jpg, 1.9 MB).

During the 2017 Gulf of Mexico expedition, the only macrofauna spotted living directly on methane hydrate outcrops were ice worms, Hesiocaeca methanicola. These pink hesionid polychaetes are 2-4 centimeters (~0.8 to 1.6 inches) long and were first discovered two decades ago living on seafloor hydrate mounds at 800 meters (~2,625 feet) water depth in the Gulf of Mexico. The worms can live in communities as dense as 3,000 individuals per square meter (one square meter is ~10.8 square feet), although far fewer individuals were seen on exposed hydrate during Dive 17.

The orange-stained, massive gas hydrate, which is covered with sediment and probably interspersed with carbonate rock, likely forms the structure of the hydrate mound. Porous gas hydrate formed around gas bubbles as they are emitted from the seafloor beneath the overhang is visible in the center of the photo, just left of the fish. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

Pink “ice worms” are visible beneath the overhang in the center left part of this photo. Ice worms were also seen in some of the burrows in the surrounding gas hydrate, which appears orange due to impurities. Active methane emissions occur from beneath the ledge, through conduits at the base of the inverted droplets attached to the sediment and through a bubble tube at the right of the image. Both the bubble tubes and the inverted droplets are encased in clear gas hydrate. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download map (jpg, 984 KB).

Imagery collected during the dive revealed that the ice worms had burrowed into the hydrate, creating small depressions. The worms are known to colonize not only exposed hydrate, but also hydrate buried beneath 10 centimeters (~3.9 inches) or more of sediment cover. When first discovered, ice worms were thought to host endosymbiotic chemosynthetic bacteria that used the abundant hydrocarbon-rich fluids to create food. However, it is now known that the worms graze on bacteria growing on the hydrate.