by Dave Wright, Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration

July 15, 2017

Another day at the office for Dave, piloting the ‘tour-bus for science.’ Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 Laulima O Ka Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 18.2 MB).

Dave Wright, senior ROV pilot and self-taught engineer, has worked with NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer since 2008.

There are only two members of the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) team without a degree. I am one of them; my boss is the other.

Forty-odd years ago, I was pushing a fully loaded wheelbarrow out of the barn on my way to the pile, when it occurred to me that ‘Equine Waste Products Management Specialist’ was a no-growth career path. My other skill, ham radio, was a hobby—back when you couldn’t pull a phone out of your pocket and call the far side of the planet. You needed large equipment and, more importantly, some knowledge of how it was supposed to work. However, there were handbooks and manuals oriented towards learning by doing. If you were willing to study, you could talk to the far side of the planet on a good day. I studied.

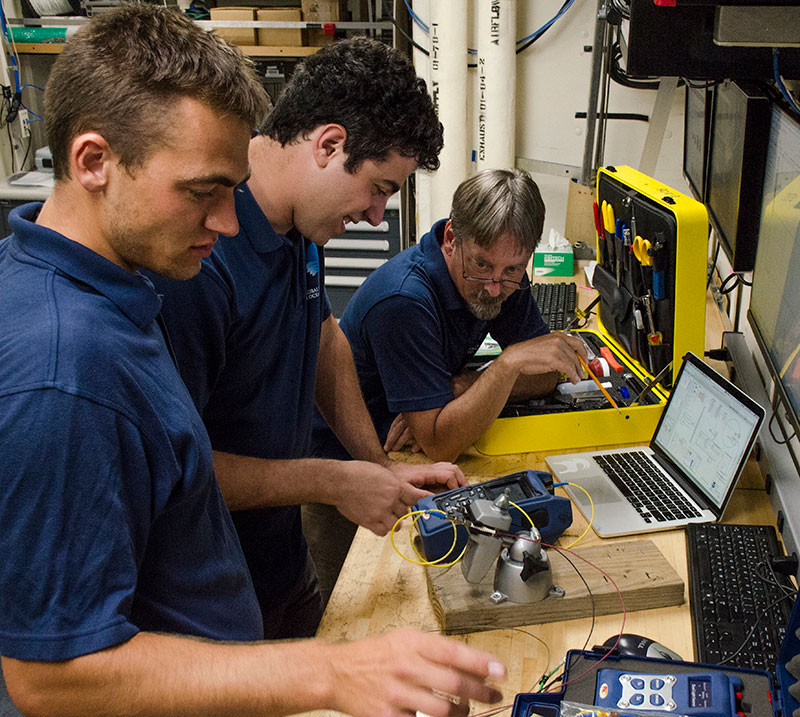

Electrical engineers Levi Unema and David Casagrande picking up on some of the finer points of fiber optic measurements from Dave Wright. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 Laulima O Ka Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 11.3 MB).

One Sunday dinner, during the equine days, Dad delivered the ultimatum: “You can go to college now, and I will pay for it. But I won’t pay for it later. Or, you can get a job and start paying rent to live here at home. Your other choice is to move out and do whatever you like. You have two weeks to decide.” Well, that brought things into focus pretty quickly. The newspaper held hope in the want ads, ‘Electronics technician, digital, travel, call 895-1234.’ I went for an interview. In the room were graybeards from the local General Electric plant, laid off with years of experience under their belts, and me, a kid.

I had been studying digital logic, knew something of microprocessors, and wanted to know more. The interviewer went right to the point, “You have no degree, no trade school, no way for me to know if you know what you say you know, why should I hire you?” “Give me a test,” I responded, “any test that will make you comfortable with choosing me.” He responded, “I’ll call you in a couple of days,” and showed me the door. He didn’t call, but I did.

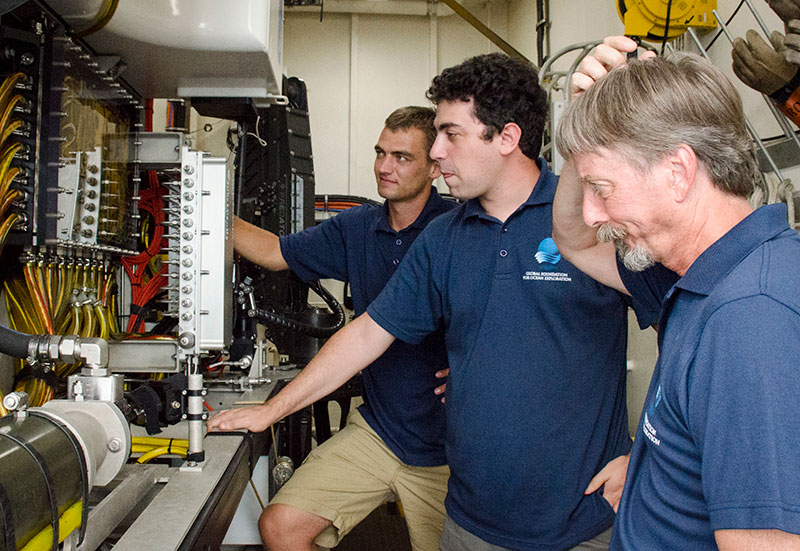

A good question deserves a good answer. Dave Wright endeavors to explain noise suppression in the Deep Discoverer thruster control communications. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 Laulima O Ka Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 10.0 MB).

When I sat down for my test, he laid out an E-sized blueprint (yes, they were blue then) of the logic schematic, circles a section with his finger and says, “Draw a timing diagram of this circuit here.” Gulp, timing diagrams were something that still had a steep learning curve for me back then. Never mind, I thought, and I took my best shot.

Something was funny, as I began to follow the logic. It chased its tail, feeding back on itself and adding an external input. I drew, erased, drew again. The interviewer would walk in periodically, look over my shoulder and then quietly walk out. Finally, handing over the pad, I said, “I think this is what is going on.” He stared at the page, saying nothing. How poorly could I have done? Time stretched out. He looked at me and said, “You are the only one who has gotten this correct.”

At dinner, when the two weeks had passed with nary a prod from Dad, came the question, “Well son, what are you going to do?” I replied, “I have a job, I’m moving to Huntsville, I leave this week.”

What followed over the years were a series of jobs in electronics, each one just a little bit over my head upon entry, but I was motivated to crack a book or find a tutor to figure things out.

Now, my day usually starts before the sun is up, with coffee on the bow and pink clouds glowing in the dawn. Dreams of the perfect ship, with systems designed fresh and a decade of experience to inform the plan, filling my mind. Walking aft, I survey what we have—a Medusa of connections, mysterious wires, an evolutionary reality of selection pressure on a compressed timescale.

We must dive today.

The data must flow.

We must do it again tomorrow, be ready.

Sleep is optional.

What you see from shore is a production. What you do not see are most of the men and women behind the curtain. The scurrying to troubleshoot the satellite link, the broken instrument to be replaced or repaired, ships’ engineers urgently troubleshooting the dynamic positioning system. Meetings, meetings, meetings...

I’ve learned a little bit about a lot of things on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. When I’m not in the pilot seat flying Deep Discoverer, I walk around, listen, look for places I can pull on an oar and keep our ship moving forward. I am happy with the path I chose.

The point of this story, for those readers who did not do well in school or did not find a formal program to their liking, is this: education is not something you can only get in school. Education is a discipline that you practice in your own mind. You do the work, not for a teacher or professor, but for yourself.

So pursue what interests you, and become good at it. Be ready and able to prove your abilities, you will be challenged. If you fail, study more, and go back again. Perseverance will be rewarded.

It has been said: “In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” And that is my role now, to mentor new minds to apply their knowledge while out here bouncing across the sea. How to figure it out, fix it, and then go fly it.

Today, as I write this, I can look back on almost 10 years of work aboard and for this ship. A younger generation of engineers has taken the controls, and they are good at it. Who will be the next great explorer and what equipment will they build?