By Jeffrey Drazen - University of Hawaiii at Manoa

June 20, 2016

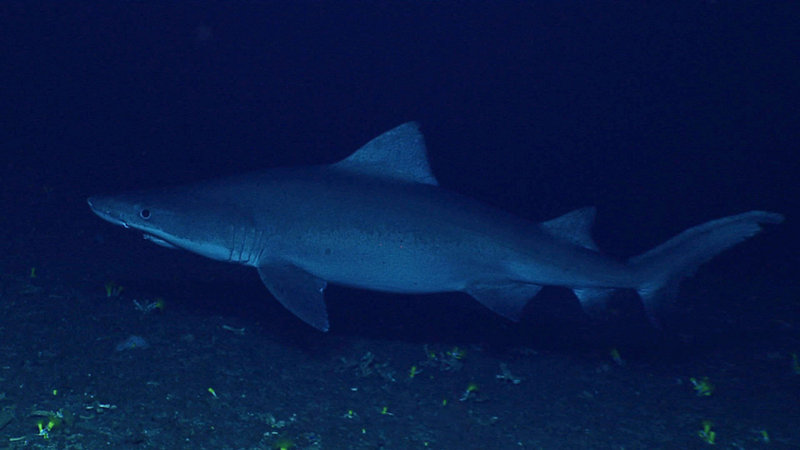

During the second dive of the expedition, while exploring Pagan at a depth of ~400 meters (1,312 feet), we encountered this sandtiger shark (Odontaspis ferox), which measured ~ 1.5 meters (five feet) in length. Video courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download (mp4, 23.6 MB).

When most people think of sharks, they get images from the movie Jaws of a huge great white or they think of sleek, fast reef sharks, high fins cutting through the surface of the ocean. As with so many other animals, deeper living species have a different appearance and often a slower pace of life due to low light levels and temperatures.

Deep-sea sharks can have long bodies with a small dorsal fin far back on the body. Many are quite small and feed on krill or small benthic animals. Studies have shown that the metabolism, or pace of life, of many deep-sea sharks and rays is much lower than their shallow water counterparts. Video observations confirm that many slowly swim across the seafloor in contrast to our stereotypes of sharks from coral reef habitats.

Smalltooth sandtiger shark (Odontaspis ferox), believed to be pregnant, seen on Leg 3 of the 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 628 KB).

On the third dive of Leg 3 of the 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas expedition, we saw a smalltooth sandtiger shark (Odontaspis ferox). It was a rather large specimen and judging by its huge belly, it was pregnant! This was a rare sighting, indeed!

Deep-sea sand tiger sharks reproduce very slowly. Typically, only two pups are born every couple of years. When the pups are born, they are already at about a meter in length! This shark has a very interesting reproductive strategy in that the eggs develop within the mother’s uterus using the yolk provided; but, when they run out of that yolk, the mother has other unfertilized eggs in the uterus that the babies then eat. This is called aplacental viviparity – the babies are carried by the mother and grow in her uterus, but without a placental attachment like we see in mammals. Indeed, many sharks are viviparous with variations on this strategy, though many others lay eggs directly onto the seafloor.

A deepwater catshark (family Scyliorhinidae) in the genus Apristurus encountered in the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument earlier this year. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Sharks don’t reproduce quickly which makes them vulnerable to fishing pressure. Recent studies have shown that deep-sea sharks reproduce even more slowly. They are slower growing, reach sexual maturity later (10-25 years), and have fewer offspring each time they reproduce. This pattern matches what we know of their slow metabolism. And the implications for the sharks are dire.

Deep-sea fishing began a great expansion in the 1970s and continues to this day. Sharks are frequently captured, but most have flesh that is considered unpalatable, or at least undesirable, and they are often discarded. This fishing occurs from a few hundred meters down to 1,500 meters deep using large trawls or long lines of baited hooks. The sharks and fishes that are caught, even if they are discarded, typically don’t survive the capture process—being hauled up to low-pressure, high-temperature waters and into a boat. This has resulted in the death of many of these slow-paced and slow-growing creatures and their populations have dropped dramatically in many cases. Efforts are underway by some governments, scientists, and other organizations to restrict fishing to only shallower depths where species have a faster pace of life and are better adapted to cope with fishing pressures.

There is very little deepwater hand-line fishing in the Mariana Archipelago, as large scale deep-sea fishing hasn’t developed there. So we can hope that the pregnant smalltooth sand tiger shark we saw can give birth to her pups and live for many more years to come.