By Michael S. Trianni - NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center

Mixed catch of Onaga, Etelis coruscans (solid color) and Gindai, Pristipomoides auricilla (barred). Image courtesy of M. Trianni, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 3.4 MB).

The cultures of the indigenous inhabitants of Micronesia are characterized by an intimate relationship with the ocean. This seafaring bond is realized most strongly through fishing, an activity which has sustained Micronesian cultures for millennia.

Throughout the Mariana Islands, archaeological evidence has revealed that a wide array of fishing techniques were used during the prehistoric period to capture fish ranging from shallow reef-associated species to pelagic species such as mahi mahi and marlin. Because fish remains can typically be identified only to the family level, archaeological remains cannot inform whether deep-slope (depths beyond 150 meters/450 feet) bottomfish were harvested in the past. It therefore remains unknown whether the Marianas’ indigenous inhabitants harvested deep-slope fish communities.

The Mariana Islands were claimed by Spain following the 1521 expedition by Ferdinand Magellan. During the Spanish Period, indigenous fishing was restricted and historical information on fishing is limited to missionary and other historical accounts. The Mariana Islands were partitioned following the Spanish-American War. The island of Guam was ceded to the United States in 1898, and the Northern Mariana Islands were sold to Germany in 1899. The German Period saw a general relaxing of fishing restrictions, and long-held fishing skills began to re-emerge.

The Eight-banded Grouper, Hyporthodus octofasciatus. Image courtesy of H. Tran, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 6.7 MB).

During World War I, Japan took the Northern Marianas from Germany. Following the war, control of the Northern Mariana Islands was delegated to Japan by the League of Nations under the South Seas Mandate, which also included other islands controlled by Germany in Micronesia. The period under Japanese control became known as the Japanese Administration, which lasted from 1914-1944. During this period, the Northern Mariana Islands were used for sugarcane production, as well as fishing, with Saipan serving as an important Japanese port in Micronesia.

It was during the Japanese Administration that fishing in the Northern Marianas reached its zenith, although landings were generally dominated by pelagic and nearshore species. Landings records from the Japanese Administration did not mention or note bottom fishing or bottomfish species.

During the Trust Territory period (1944-1976) under U.S. Administration, reported landings continued to be dominated by pelagic species, although non-pelagic “reef fish” were also documented. It has not been established if non-pelagic landings included any deep-slope bottomfish.

Bottom fishing was first distinctly documented during the early years of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI, 1978-present), when the Commercial Purchase Database (CPDB) data collection program was instituted collaboratively with the CNMI Division of Fish and Wildlife by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Western Pacific Fishery Information Network (WPacFIN), currently under the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center.

The bottomfish fishery in the Marianas includes two distinct targeted complexes. The shallow-water complex (50-100 meters/~150-300 feet depth) is an extension of the reef-building coral complex dominated by the Emperors of the family Lethrinidae. The deep-slope complex (>150 meters/~450 feet depth) is characterized by the snappers of the family Lutjanidae (genus Pristipomoides and Etelis), and one member of the family Epinephelidae (the Eight-banded Grouper Hyporthodus octofaciatus). In general, snappers of the genus Pristipomoides are caught at slightly shallower depths (150-250 meters/~350-750 feet depth) than snapper species in the genus Etelis and the Eight-banded Grouper (>250 meters/~750 feet depth).

The deep-slope bottomfish resources in the Marianas encompass the islands, banks and reefs over the entire 400-mile long chain, from Santa Rosa Reef south of Guam to Uracas Bank north of Farallon de Pajaros. Additionally, the West Mariana Ridge that parallels the main island chain also harbors deep-slope fishery resources.

The CPDB collects data on pelagic, reef, and bottomfish supplied voluntarily to the CNMI Division of Fish and Wildlife. In the CPDB, bottomfish (shallow and deep) have never surpassed 17 percent of the reported total commercial fisheries landings. Landings of deep-slope species are historically low because of the challenges of collecting fish from deep seafloor depths.

Technological advances including Global Positioning Systems (GPS), hydraulic gurdies, and electric reels have provided access to these resources, enabling harvest at specific locations with fast retrieval times that minimize shark depredation.

The CNMI deep-slope commercial bottom fishery landings began increasing in 1994, coincident with CNMI economic prosperity, with several large vessels (>40 feet) operating in the islands north of Saipan targeting Onaga (Etelis coruscans) and the Eight-banded Grouper. Landings peaked at almost 40,000 pounds in 1996, although in recent years landings have declined to an average of about 10,000 pounds. No reliable information is available for recreational and subsistence landings of these fish.

Bottom Camera Bait Station (BotCam) bottom image from Sariguan Island, showing heterogeneous bottom structure on a deep-slope habitat. Image courtesy of Chris Kelley & the PIFSC Coral Reef Ecosystem Program. Download image (jpg, 43 KB).

The deep-slope resources have been assessed twice by NMFS, the first occurring along the main island chain and banks of the West Mariana Ridge from 1980-85 during the Resource Assessment Investigation of the Mariana Archipelago (RAIOMA). The results from RAIOMA included incipient seafloor mapping and deep-slope fish yield assessment.

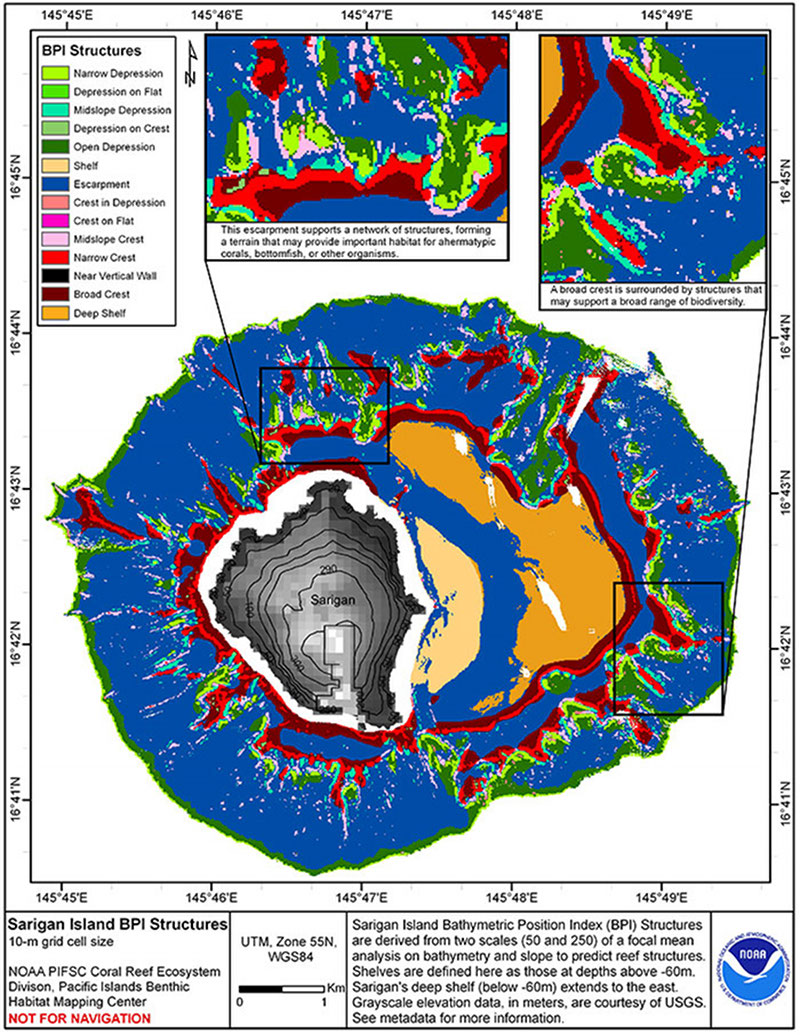

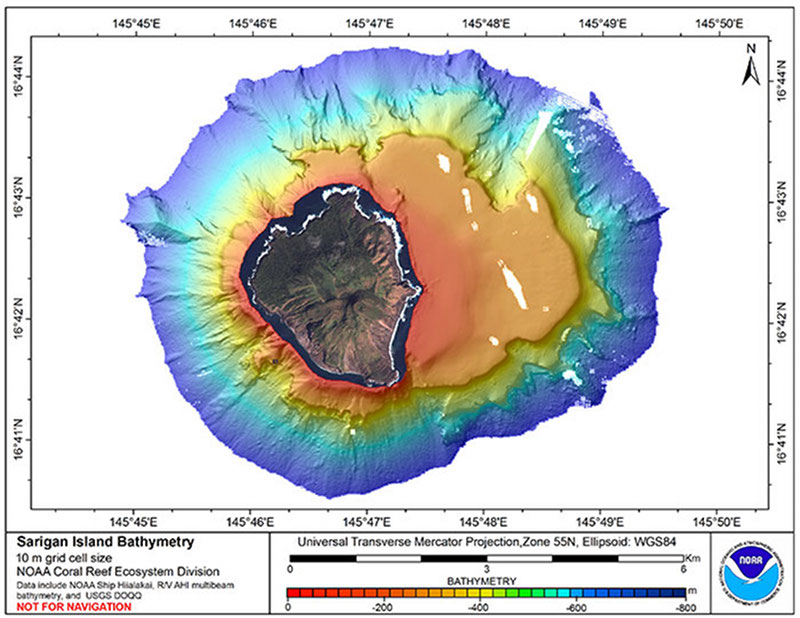

In 2014, life history data were collected from deep-slope resources along the main island chain, in order to better understand within-species geographic variations. Side-scan sonar, multibeam bathymetric, and some Bottom Camera Bait Station (BotCam) data have been collected at several islands and banks in the Marianas since RAIOMA, providing detailed depth and geomorphological data.

Work remains to be accomplished to ground truth mapped structures using remotely operated vehicles to more accurately identify preferred deep-slope bottomfish habitats. This information will contribute towards providing a better understanding of species-specific habitat requirements so that future assessments of these lightly exploited resources in the Marianas will supply fisheries managers with more accurate projections of sustainable fishery yield.

Gridded geomorphological map of Sariguan Island. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 4.7 MB).

Processed multibeam bathymetric map of Sariguan Island. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 2.7 MB).