By Scott C. France, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Colonies of Hawaiian bubblegum coral at 350 meters depth with anemones, brittle stars, and other animals living in their branches. Image courtesy of NOAA-HURL Archives. Download larger version (1.3 MB).

If you think of tropical Hawaii and corals, likely what immediately jumps to mind is snorkeling over gorgeous coral reefs teeming with colorful fish. But much deeper below the waves, beyond the depths at which sunlight-dependent reef-forming corals can grow, exists the hidden, perpetually dark world of deep-sea corals.

We expect deep-sea corals will be among the more conspicuous animals we will see on the deep seamounts and ridges explored during this expedition. Deep-sea corals are of much interest to scientists/biologists as these corals provide habitat complexity to the ocean floor, just as trees turn an open plain into a structurally varied three-dimensional environment. And, as in the branches of trees, many organisms live among the corals, such as shrimp, crabs, barnacles, brittle stars, feather stars, worms, fish, and more.

Before we go any further, let me define what a coral is. To some readers, “coral” conjures up images of stony material that forms the structural base of shallow tropical reefs. Others will think of plant-like sea fans or soft gelatinous “dead man's fingers,” or even red, pink, or glossy black jewelry. And all of these are coral!

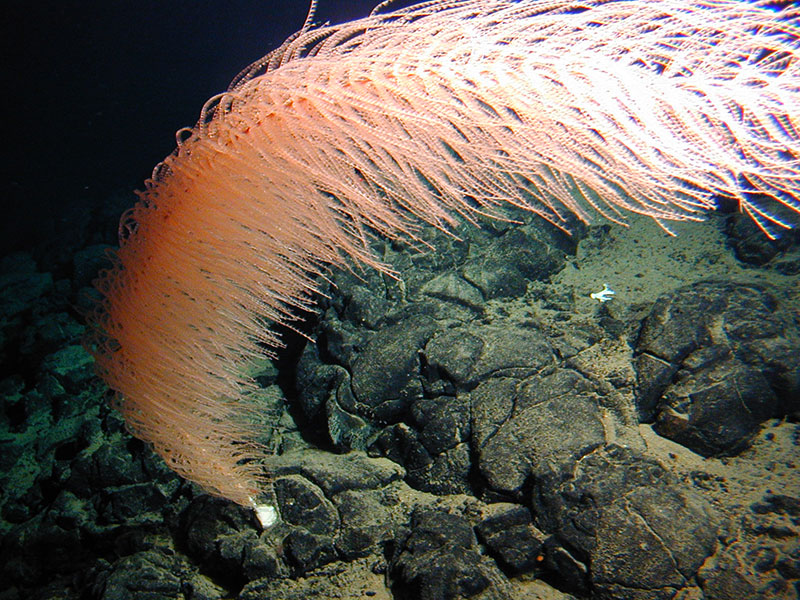

A Hawaiian species of gorgonian called Rhodaniridogorgia bending in the current. Image courtesy of NOAA-HURL Archives. Download larger version (1.3 MB).

Corals are sessile, which means that most, but not all, are solidly attached to a hard surface or are anchored into sediments (such as sea pens). This presents some interesting challenges when it comes to reproduction and dispersal. Like trees scattering their pollen, most corals are broadcast spawners: males release their sperm into the water and females may do the same with their eggs or hold the eggs until they capture sperm to fertilize them.

Despite these similarities to trees and plants in terms of their structure, sessile nature, and reproduction, corals are animals, not plants.

Corals are invertebrates, members of the Phylum Cnidaria. Other familiar cnidarians include jellyfish, Portuguese Man-o-War, and sea anemones. The basic body form of a coral is the polyp (you can learn more about the different kinds of polyps in the essay, “Cerianthids, zoanthids and anemones… Oh my!”).

A polyp is a sac-like body with a single opening that is surrounded by tentacles. The tentacles are studded with thousands of tiny sub-cellular structures called cnidae (pronounced “nye-dee”) that can be fired as tiny threads, some of them sticky and others penetrating like a miniature harpoon. Cnidae are also found in many other places on the polyp and even within the “stomach” (gastrovascular cavity).

Tentacles wave in the water column and with the help of the cnidae, can capture prey such as small shrimp and other crustaceans. Many shallow water corals have living in their cells photosynthetic symbionts that convert sun’s energy into food molecules, thus reducing or eliminating the need to capture prey.

While some coral species exist as solitary polyps, most corals are colonial. Colonies of polyps form when the initial polyp buds off a new polyp, and the two remain attached, even sharing a continuous gastrovascular cavity so that food in one polyp can be shared with others. Repeated budding can produce a colony with hundreds of thousands of polyps.

As noted above, these polyps can also produce gametes (sperm or eggs), which after fertilization lead to a larva that settles and grows into a polyp, which can establish a new colony. Colonies may be branched like a bush or tree or unbranched like a whip, or grow as mounds, mats or even ribbons over the bottom.

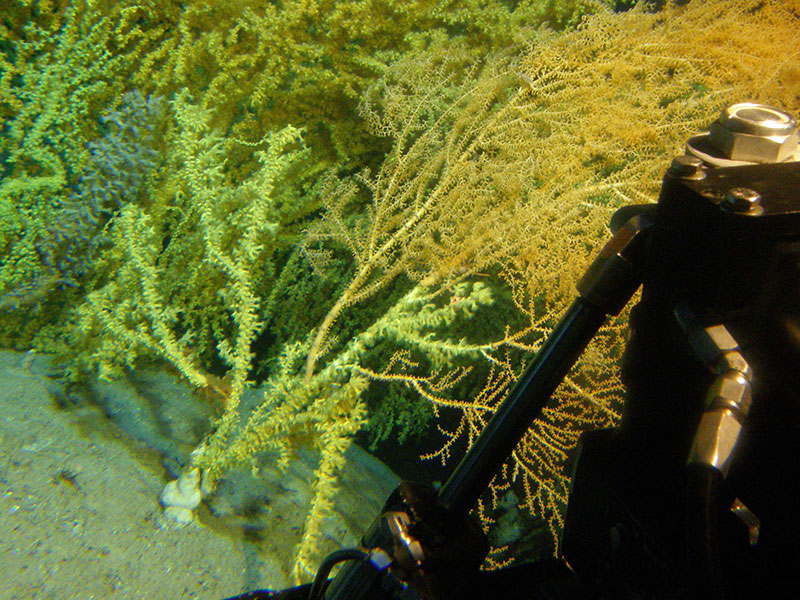

Gold coral (yellow) in the process of overgrowing a bamboo coral colony (orange) that it will eventually completely cover. Image courtesy of NOAA-HURL Archives. Download larger version (4.5 MB).

On this expedition, we should encounter several major groups of corals: Octocorallia, Antipatharia, Scleractinia, and Zoanthidea.

Octocorals (which include sea fans, bamboo corals, soft corals and sea pens) and antipatharians (black corals) have skeletons that are made partly from protein and so are flexible.

Scleractinians are stony corals and have a skeleton made of rock hard calcium carbonate making them quite inflexible. And finally, gold corals (zoanthideans) begin their colony formation by overgrowing octocorals and black corals and then expanding to a larger size by producing their own protein-based skeletons.

The study of deep-sea corals around Hawaii began more than a century ago. The U.S. Fisheries Commission Steamer ‘Albatross’ sampled 52 species of octocorals around the main Hawaiian Islands in 1902. In the early 1970s, the ‘Sango’ Expedition undertook to study the distribution of precious corals (those whose skeletons are used to make jewelry) around the islands and added knowledge of 41 additional species to the Hawaiian fauna. More than a dozen new species have been described since 2008 and many more remain to be formally described.

Because there have been few remotely operated vehicle or submersible dives deeper than 1,500 meters on the seamounts and ridges around Hawaii, during the Hohonu Moana expedition, we expect to discover more corals previously unknown from these waters.