By Susan Schnur - Oregon State University

September 30, 2014

Science Lead Scott France and Assistant Scientist Susan Schnur hard at work in the control room at the end of a dive. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

On every telepresence-enabled remotely operated vehicle (ROV) cruise on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, two research scientists have an opportunity to join the floating community of mariners, engineers, and data and video specialists that calls the ship home. The scientists help plan dives, narrate dives live on a publicly available video stream, and communicate with other scientists on shore to make sure the exploration objectives of the cruise are being met. Every sub-group on the ship has a daily routine of its own, and the science team is no exception.

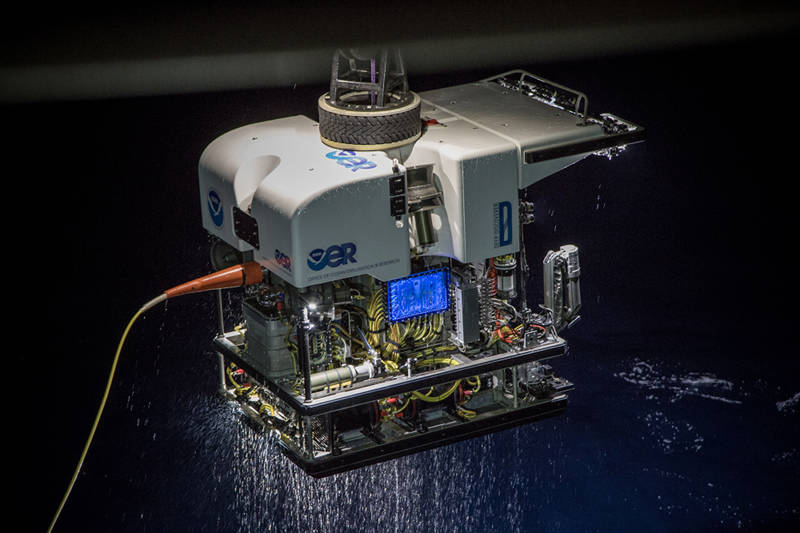

ROV Deep Discoverer is recovered after an extended dive. Although D2’s recovery means the end of the day for several of our viewers, our onboard team still has lots of work to do after every dive. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

For me, a typical day on the ship starts somewhere around 6:30 am. Due to the highly variable weather we have been experiencing, I usually start up my laptop as soon as I get out of bed so I can check for updates on the dive status. On several occasions, dives have been canceled due to bad weather or delayed due to strong currents.

The ROV is usually deployed at about 8 am. Prior to that, I eat breakfast and organize my "desk" in the control room. I prepare for the dive by setting up spreadsheets to record observations and by doing research on topics I plan to talk about during the dive. For example, researching the geologic origins of a feature we will be exploring or finding some interesting facts to fill times when both biology and geology observations are sparse.

On other types of research cruises, a much larger science team may be split into two or three watches so that data and samples can be collected around the clock. On Okeanos Explorer, we must overlap with the working hours of scientists on shore as well as respect the work contracts of the crew. Standard dive hours therefore start with deployment at 8 am and end with retrieval of the ROV at about 5 pm. On special occasions, such as for a deep dive, the ROV can stay in the water until 7:30 pm.

Once the dive begins, curtains are drawn around the control room doors and the room is darkened. The only light is from the glow of computers and TV screens. Soon after leaving the surface, the video team starts up the conference call line that the shore-based scientists can use to call the ship from their office telephones. The scientists log onto the science chat room to start discussing the dive. Once on bottom, the exploration begins!

Both on-ship scientists stay glued to the screens until about 11:30 am, when they trade off to each take 20-minute lunch breaks. In order to be at the surface by 5 pm at latest, the ROV must depart bottom at about 3:30 pm. Immediately after leaving bottom, the science team has a scheduled teleconference with the shore-based scientists. During the meeting, we decide on a dive plan for the next day, discuss weather forecasts, and think about longer-term dive targets. This meeting usually lasts about 15-30 minutes.

Meals on the ship are spaced closely together to reduce the long working hours of the cooks, so by the end of the science meeting, it is often time for dinner. After dinner, the work day is not yet over! The science team must still prepare the formal dive proposal for the next day so that it can be emailed to the shore-based scientists. After each dive, the onboard scientists must also prepare a formal written summary of their observations during the dive.

Added to this, there are the usual tasks of keeping up with email from colleagues on shore and, in my case, making progress on my PhD research. I usually work for the rest of the evening, until about 10 or 11 pm, at which time I am ready for bed. This schedule does not change much for dive days, unless weather or currents have forced us to alter our plans.

On the ship it is easy to lose track of the days of the week, as there are no weekend holidays at sea! Fortunately, there are various morale-boosting events to help break up the routine. Once a week, there is an ice cream social in the mess hall and an open-air movie night on the fantail deck. All in all, the life of a scientist at sea is exhausting but rewarding!