By Rhian Waller - University of Maine

September 25, 2014

During remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer's transit today, we imaged a cup coral that had recently captured a small jellyfish for its next meal. These deep-sea corals usually eat whatever falls from above or comes close enough for them to capture with their tentacles. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Today’s dive involved over 30 scientists from all over the U.S. – even as far away as the University of Hawaii – possibly the farthest a backseat driver could possibly be from the North Atlantic.

At the Mystic Aquarium Command Center, Peter Auster, Rhian Waller, Emily Duwan, and Steve Auscavitch watch a dive on Retriever Seamount. Image courtesy of Peter Auster. Download larger version (jpg, 474 KB).

For the last few days, I've been lucky enough to join a group of scientists from the University of Connecticut and the Sea Research Foundation at the Mystic Aquarium, an amazing facility with three (very) large screens, an Internet 2 connection (providing us with near-real time video), hard drives to take screen grabs, phone connection, and even beluga whales to say hello to on walking breaks – not a bad set-up!

The ability to connect with colleagues at sea in real time and to expand exploration to a wider audience than could ever fit on a research vessel is one to embrace, and these remote command centers make the experience even more inviting to scientists like me. This way I can get out of my office and devote my full attention to this cruise, see areas of the seafloor that no one else has seen before, and interact with colleagues who have a deep interest in this environment; but, I still get to sleep in a comfy, non-rocking bed and choose which restaurant I'll have dinner in at night. It's really a great combination of both worlds – though the folks at sea have a lot of backseat drivers to deal with!

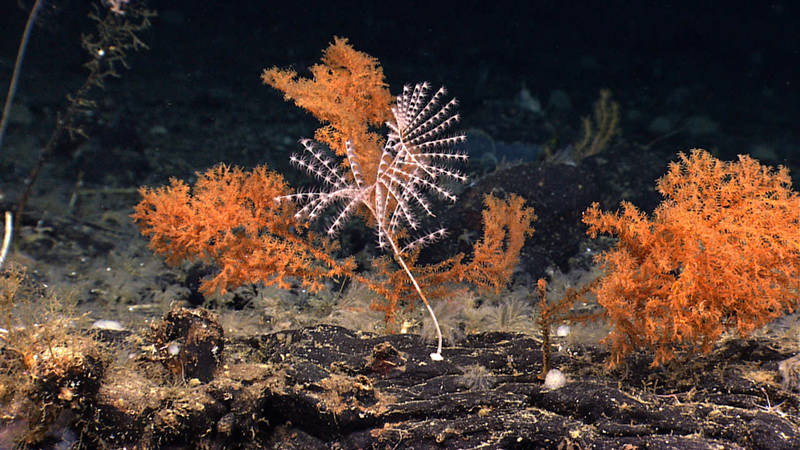

Here, two colonies of black coral have made their home next to a spiraled Iridogorgia octocoral. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

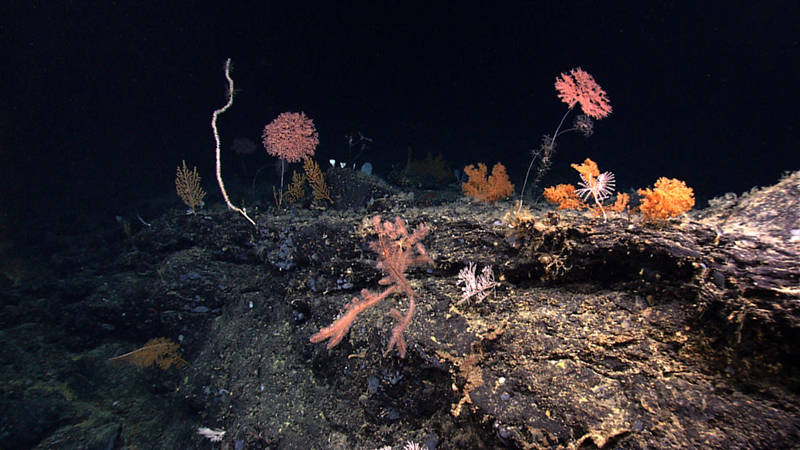

Today’s dive may not have been the most "corally" that has happened on this expedition (my expertise is in deep-sea coral reproduction), but it was an extremely interesting look at a remote and understudied environment. We started the morning in a flat area covered in pebbles with sparse cup corals and sea pens. As we came up slope, boulders came into view; one by one they got larger and larger, until we finally reached a small scarp of volcanic rock.

This view reminded me of why I like to devote my time to deep-sea exploration – one, then two, then three, then four different species of coral came into view, until we could see maybe a dozen different species of coral, some sponges, lots of crabs, sea stars, anemones, and more. Scientists from all over chimed in with species identifications and requests to look at "another coral over there," until the rocky face was thoroughly characterized. These boulders and rocky habitat quickly become oases, as larvae come in and settle perhaps the only hard bottom for long distances.

One spectacular hard rock area had a very high coral diversity during this dive. This one image has bamboo corals, black corals, and octocorals, all living together to form a community. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Then we were back into the sediment lands, still teaming with life, just different and less visually dramatic than that seen on rocks. The excitement for me was seeing fields of cup corals, which happen to be one of my favorite organisms.

Unlike the large tall colonies and "trees" that contain hundreds of genetically identical polyps, these are single polyps all alone, and so single individuals with their own hard skeleton genetically distinct from one another. Their larvae settle on tiny pebbles, which they quickly overgrow and then anchor or lay across the sediment surface. And here they spend their long lives (some we think live for over a hundred years), waiting for food to fall from above or to come within tentacle reach, producing gametes that will hopefully be fertilized by a neighbor and become a new coral, and forming a little bit of habitat for other sediment-living organisms.

The exploration continues - tomorrow we're on to more seamounts, weather permitting!

A cup coral shows off its translucent orange tentacles, filled with nematocysts - stinging cells they use to capture prey. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).