By Scott C. France, Associate Professor of Biology - University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Lava flows can have different morphologies based on how quickly they were extruded. Pillow lavas are a common and very striking type of flow seen at seamounts. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson authorized the Louisiana Purchase, a land deal that saw the United States acquire from France 827,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River. At this time, most inhabitants of the U.S. lived within 50 miles of the Atlantic Ocean and there was little knowledge of what would become the American West.

President Jefferson thus commissioned the Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore the West. The National Park Service writes, “By any measure of scientific exploration, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was phenomenally successful in terms of expanding human knowledge and spurring further curiosity and wonder about the vast American West.”

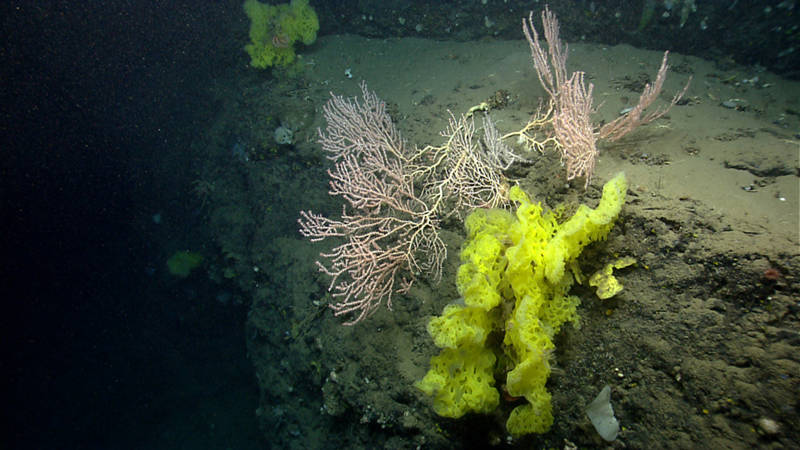

A large Jasonisis bamboo coral, re-growing upwards after falling over, and yellow-green glass sponges grow from the edge of a small sediment-covered ledge at 1368 meters depth in Nygren Canyon. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

More than 200 years after the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a new frontier beckons - this one eastward from the U.S. Atlantic coastline. Deep below the smooth surface of the ocean hides a complex and dramatic topography, a still largely unexplored, underwater landscape as stunning as that seen by Lewis and Clark in the west.

Less than 200 kilometers (120 miles) offshore of New York, the relatively flat, submerged continental shelf transitions to the continental slope, descending more than 4,000 meters into the abyssal zone. Between Norfolk, Virginia, and Cape Cod/Georges Bank, this slope is slashed by more than 13 major canyons and dozens of smaller ones.

For example, Hudson Canyon extends over 640 kilometers from the New York-New Jersey Harbor to its mouth, four kilometers down into the deep ocean basin, and is as wide as 10 kilometers. To put that in perspective, the Grand Canyon is 446 kilometers long, up to 29 kilometers wide, and 1.6 kilometers deep.

Stretching offshore from the slope off Cape Cod are the New England Seamounts, a chain of more than 30 volcanic peaks, some greater than four kilometers high/tall, that extend over 1,100 kilometers to the southeast. This is comparable in geographic scale to the Cascade Volcanoes of the Pacific Northwest.

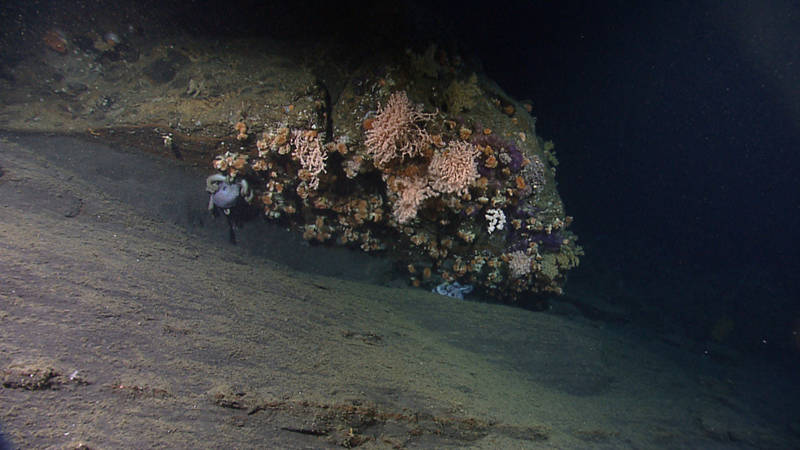

Currents sweep past an overhang of rock at 1,152 meters depth in Oceanographer Canyon, creating an ideal microhabitat for a deep-water coral community and a couple of octopods. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

This deep-sea frontier is rich in resources. Submarine canyons have more abundant and diverse megafauna (large animals such as fish and crabs) than the surrounding deep-sea slopes. The “V” -shape of canyons channels currents along their axis, and this funneling effect results in nutrient enrichment (when more food is carried into the canyon than over the slope), allowing for greater densities and higher biomass of animals.

In addition, where most of the shelf and slope are draped in soft sediments (mud, sand, silt, clay), enhanced currents in canyons expose extensive areas of hard bottoms, such as steep-sided walls, ridges, rubble fields, and isolated rocks and boulders. This diversity of substrata leads to increased biological richness in canyons. In particular, hard bottoms provide stable attachment sites for sessile suspension and filter feeders, such as corals and sponges. Deep-sea corals, in turn, create complex habitat, or “biogenic structures,” for other organisms, much as trees do for forest-dwelling animals, further enriching local biodiversity.

The soft sediments of canyons are by no means barren. Sea pens and burrowing tube anemones protrude from the bottom like the occasional trees on a savanna. Sediments are riddled with holes and tunnels that are inhabited by a number of species, including red crabs and tilefish. And abundant mobile invertebrates, such as sea cucumbers, sea urchins, brittle stars, and sea stars roam over the surface, feeding on organic material deposited in the sediments.

Several paramuriceid seafans (octocorals) live near the edge of a cliff wall at 1,136 meters depth in Oceanographer Canyon. Sea anemones, brittle stars, and barnacles live among the branches of the corals. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Animals living in the water column, such as shrimp, squid, jellies, and fish, may become concentrated in canyons as they migrate vertically and are funneled by the walls of the canyon.

The continental margin (the shelf and slope) is also of great interest geologically. It is estimated to harbor millions of barrels of oil and trillions of cubic feet of natural gas. Canyons are the main conduits for the transport of sediments from the shelf into the deep sea, and the stability of rocks and sediments are critical to marine geohazards such as submarine landslides.

Similar to canyons, seamounts are hotspots of biodiversity. Volcanic seamounts arise as islands of hard bottom out of the soft sediments of vast abyssal plains, and thus serve as a focal point for hard-bottom fauna and the communities that associate with them. Many commercial fish species concentrate over seamounts.

Not all submarine canyons and seamounts are alike; variation in physical structure, hydrography, and geological activity creates spatial and temporal heterogeneity in factors that affect the substrata and fauna, leading to differences in faunal assemblages. Our knowledge of the Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts and their resources are based on relatively few studies, and we have actually seen very little of them.

The most extensive visual exploration of this area came during the Okeanos Explorer Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013, when more than 10 canyons and Mytilus Seamount were explored. However, many more canyons and seamounts remain unexplored. Even those that have been visited have had only a small fraction of their total area revealed – imagine seeing only one segment of one wall of the Grand Canyon.

This expedition will enhance our overall knowledge of Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts and their resources.

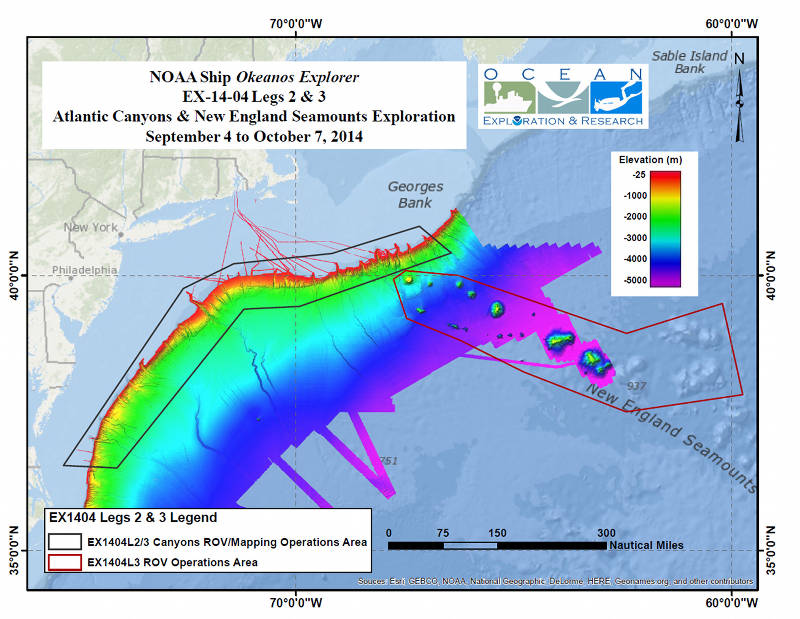

Map showing areas that will be explored during the second and third legs of the Our Deepwater Backyard: Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014 expedition. Color-coded bathymetry, previously collected by Okeanos Explorer and by the University of New Hampshire’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping UNCLOS expeditions, processed with QPS Inc., Fledermaus software. Map created with ESRI ArcMap software. Download larger version (jpg, 829 KB).