By Tim Shank, Associate Scientist - Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

and Jim Holden, Associate Professor - University of Massachusetts-Amherst

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents and their associated biological communities were first discovered on the Galápagos Rift in 1977. The discovery of life thriving in the absence of sunlight and nourished by chemicals in the vent fluids profoundly and permanently changed our view of how and where life could exist. It fundamentally changed the biological and earth sciences and our view of the deep sea. It also opened the door for biologists, chemists and geologists to explore the fundamental properties and complex interactions between magmatic, hydrothermal, chemical and biological processes along the global mid-ocean ridge system.

One of the first images of black smokers on the Galápagos Rift (the Navidad vent field) in December 2005. Image courtesy of GalAPAGoS Expedition 2005. Download larger version (jpg, 745 KB).

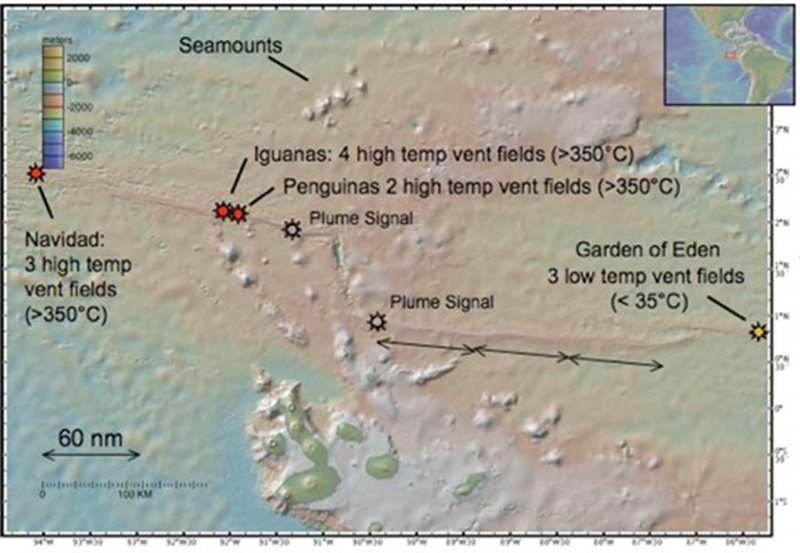

Map of some of the high-temperature and low temperature vent fields and plume signals known prior to GALREX 2011. Image courtesy of GalAPAGoS Expedition 2005. Download image (jpg, 90 KB).

In May 2002 and June 2005, two NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration expeditions occurred on the Galápagos Rift between 86ºW and 89.5ºW Longitude. The objectives of these DSV Alvin expeditions included revisiting the historic low-temperature hydrothermal vents like Rose Garden and the Garden and Eden (discovered in 1977) and searching for high-temperature vents along the largely unexplored western portion of the eastern rift. The Autonomous Benthic Explorer (ABE) vehicle mapped meter-scale bathymetry, near-bottom magnetics and bottom water-properties and discovered three low-temperature hydrothermal vent fields and biological communities (including Calyfield, a large clam field [below] and the shallowest known vent site on the Rift at 1690m). The iconic Rose Garden site was paved over with lava from a recent eruption, and a low-temperature vent field (named Rosebud) was found to host nascent developing communities on a fresh-looking sheet flow at a location approximately 200 meters northwest of the former Rose Garden area. Despite extensive exploration, no high-temperature hydrothermal black smokers were discovered.

In December 2005, the NOAA OE Galápagos Expedition (Galápagos Acoustical, Plumes, and Geobiological Surveys) explored a 400 nautical mile-long section of the western Galápagos Rift between 94.5º-89.5ºW, which is near the mantle plume that created the Galápagos Islands. This led to the first discovery of active high-temperature black smoker venting on the Galápagos Rift (red stars on map). This brief encounter with these new vents sites revealed more than 30 black smoker vents, vent-endemic species, including giant tubeworms, clams and mussels inhabiting sites with names such as Iguanas, Penguinas, and Navidad vent fields.

Bythograeid crabs and the giant tubeworm Riftia pachyptila found at the ‘Rosebud’ vent site. Image courtesy of Tim Shank (WHOI), Galápagos Expedition 2002. Download image (jpg, 165 KB).

The giant clam Calyptogena magnifica was seen in abundance at the “Calyfield” vent field. Image courtesy of Tim Shank (WHOI), Galápagos Expedition 2002. Download image (jpg, 152 KB).

Understanding the biology and microbiology of the Galápagos Rift has important implications for expanding our knowledge of the evolution, ecology, and biogeochemical impact of life at hydrothermal vents. For example, the hydrothermal vents of the neighboring East Pacific Rise host a rich group of more than 160 species of bivalves, worms, and crustaceans while vent habitats along the Galápagos Rift host less than 60 species, many of which are not found anywhere else on the global mid-ocean ridge system. For more than two decades, we have hypothesized that either the complete absence of high-temperature black smokers (found on every other deep-sea ridge system) or the physical presence of the Hess Deep and triple junction acts as a strong barrier to dispersal or migration and were responsible for the differences in species between the EPR and the Galápagos Rift. This summer’s telepresence cruise with the high-definition camera on the remotely-operated vehicle Little Hercules will allow us to address questions such as whether the composition, diversity and habitats of biological communities in the Galápagos high temperature fields are fundamentally different than the rest of the rift indicating differences in the underlying geochemical processes.

The wide expanses of low-temperature hydrothermal venting far from focused high temperature venting also make the Galápagos Rift an exciting place to search for microbial life within the Earth’s crust. It has been suggested that a large portion of the planet’s total biomass exists as microbes inside the ocean floor, and regions of vast low-temperature venting can often produce the largest biogeochemical changes to the chemistry of the deep ocean. This expedition also provides an opportunity to identify some of the most promising sites for future detailed study. In addition to the Rift, there are other exciting habitats that will be explored during this expedition such as the unexplored Paramount Seamounts, off-axis sulfide mounds, and deep fracture zones that may host deep-water coral and vent ecosystems.

Although deep-sea hydrothermal vent research may have started with the discovery of venting along the Galápagos Rift, the work needed at this site is far from done. New technologies such as high-definition cameras and satellite video feeds enable us to address important emerging questions about hydrothermal vent ecology and evolution. This expedition takes us closer to understanding deep-sea life at the Galápagos Rift and throughout the world.