Tim Shank, Ph.D., Associate Scientist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Riftia tubeworms, mussels, and scavenging crabs found at a hydrothermal vent site at East Wall on the East Pacific Rise. Image courtesy of C. Van Dover. Download larger version (jpg, 943 KB).

In 1977, scientists investigating the seafloor along the Galápagos Rift made a discovery that shook the foundations of biology. They found oases of animals thriving in the sunless depths around hydrothermal vents. Instead of photosynthetic plants, chemosynthetic microbes comprise the base of the food chain at vents. They obtain energy from chemical-rich fluids generated by volcanic processes on mid-ocean ridges, the 50,000-mile (80,000-kilometer) undersea mountain chain that encircles the globe and marks the edges of Earth’s tectonic plates.

Since this discovery, more than 200 vent sites and 600 hundred associated species have been discovered. And we have found that on the seafloor, as on land, distinct animal populations have evolved in different regions.

Today, we recognize six major seafloor regions—called biogeographic provinces—with distinct assemblages of animal species. Beyond the tubeworm-dominated eastern Pacific, there are two provinces in the North Atlantic, where different species of shrimp and mussels predominate at deep vent sites and at shallower ones to the north. The fourth province is in the northeast Pacific, off the U.S. Northwest coast, which shares similar species (clams, limpets, and tubeworms) with the eastern Pacific, but different species of each. Across the ocean in the western Pacific, vents are populated by barnacles, mussels, and snails that are not seen in either the eastern Pacific or the Atlantic. A search for vents in the Central Indian Ocean in 2001 found the sixth province. These vents are dominated by Atlantic-type shrimp, but also had snails and barnacles resembling those in the western Pacific.

All these regions contain the same basic ingredients to support life – chemical nutrients generated by geothermal processes at hydrothermal vent sites. So why do vent fauna differ in the Atlantic and Pacific or in the eastern and western Pacific? How do we assemble these puzzle pieces to explain the diversity and evolution of vent species throughout the world’s oceans?

Evolutionary biologists are gathering clues and sorting through events and phenomena to reconstruct the processes that generated the patterns we see today. Suspected factors include:

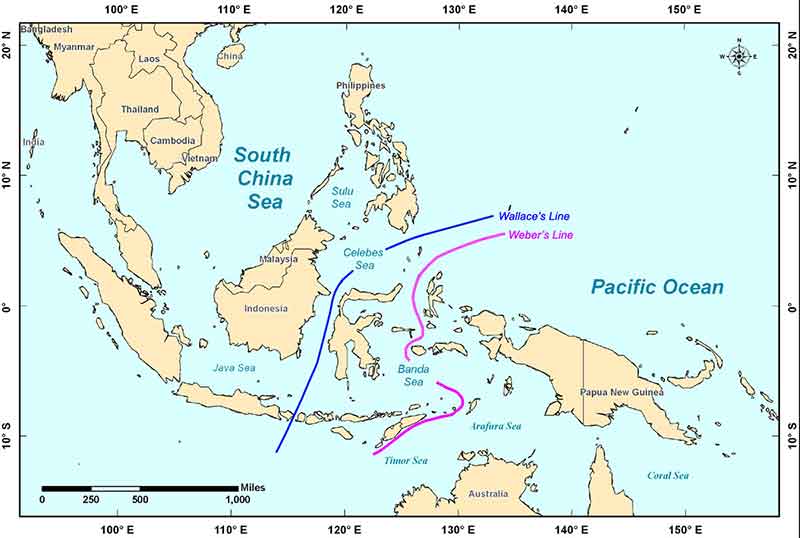

Map of the Celebes Sea region where biogeographic patterns observed on land led to lines drawn to explain breaks in species distribution. INDEX exploration of the deep sea will occur across Wallace's line – an imaginary line postulated by A. R. Wallace as the dividing line between Asian and Australian fauna in the Malay Archipelago. Weber's line is a line of supposed ‘faunal balance’ between the Oriental and the Australasian faunal regions within Wallacea. Wallacea consists of isolated islands that were never recently connected by dry land by continental land masses and thus were populated by species capable of crossing the straits between islands. Weber's line runs through this transitional area, at the tipping point between dominance by species of Asian versus Australian origin. Image courtesy of Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. 1997. Download larger version (jpg, 401 KB).

Which brings us to the Indonesian region of the world’s oceans. Why the interest? There are several classically proposed lines attempting to delineate the patterns of observed biogeography in this region between the Pacific and Indian Ocean. Historically, these lines of biogeography that denote large shifts in species distribution were largely based on the distribution of mammals (rodents) and birds and ice age information. Ocean sea levels were up to 120 meters lower during the last few ice ages. The story goes that Asia and Australia were basically united by shallow, connected continental shelves, but the deep water around them was a barrier that kept flora and fauna of Australia separated from that of Asia.

The unexplored deep sea in this region may yield a completely different story than the one that explains the diversity and biogeography of the Coral Triangle and the rest of Earth’s mid-ocean ridge system. Is there a Wallace’s line drawn in the deep sea? Is biodiversity here as high as in shallow waters in the region? Are hydrothermal vent fauna on the Sangihe Ridge the same species as off of New Guinea or the Central Indian Ocean? Are they a completely new set of life forms that we have yet to discover and add to our global biogeographic and evolutionary puzzle?

One thing for sure is that the exploration of the deep sea’s biodiversity and biogeography by the INDEX-SATAL missions will yield completely new and unknown information with which to answer these questions and explore new ones.