A healthy Oculina coral, shown here at Jeff's Reef, provides living space, shelter, and spawning habitat for numerous reef fishes and invertebrates. Click image for larger view.

Scamp are the second most important species of grouper in the southeast, but have been seriously depleted on Oculina Bank. These two were found amid habitat of sand and shell aggregate rock at Eau Gallie. This type of rock is unusual on the bank. Click image for larger view.

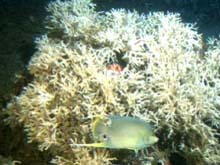

A blue angelfish on an Oculina coral head at Jeff's Reef. Click image for larger view.

Exploring Oculina Bank

August 31, 2001

Chris Koenig

Research Marine Ecologist

Department of Biological Sciences

Florida State University

Oculina Bank: Where the Fish Spawn

The reefs and pinnacles of Oculina Bank have been known as a fertile spawning ground since the late 1970s and early 1980s. At that time, scientists working in manned submersibles observed gag and scamp grouper in large spawning groups. Snowy and warsaw grouper, as well as black sea bass and speckled hind, also were observed to be abundant. Word of large groupers (gag can reach up to 80 lbs) spread rapidly to the commercial and recreational fishing communities, and the rush was on.

Generally, these fish spawned on pinnacles covered with thickets of Oculina coral heads that average about 3-4 ft across and 3-4 ft high, at depths from 200-400 ft. These topographic features make up about 3% (2.75 square nautical miles) of the 92 sq nm of the Experimental Oculina Research Reserve (EORR). The role that mud and sand flats (which make up most of the Bank) play in spawning is unknown.

Oculina habitat provides living space and shelter for numerous fish and invertebrates at different scales. Aggregating groupers use large spaces within the coral for their own refuge from potential predators, such as sharks, but also take advantage of the abundant prey harbored in the coral. Most of the small fish associated with the coral consume plankton. The large groupers and other fish-eating species prey on these plankton-eaters. Thus, both the groupers and their prey benefit from robust stands of Oculina.

Shelf-edge reefs, such as those found on Oculina Bank, are likely to enhance both the survival and distribution of spawning fish and their offspring. Specific spawning sites, such as the northeast end of Jeff's Reef, are probably traditional from generation to generation; that is, new generations of fish learn of the sites from former generations, in much the same way that birds return to the same nesting grounds.

Overfishing and the Loss of Oculina Habitat

In 1994, the South Atlantic Fisheries Management Council (SAFMC) closed the EORR to bottom fishing for 10 yrs, based on evidence that the gag grouper population was in serious decline, in order to study the problem. When scientists studied the area in 1995, the coral was annihilated and no grouper aggregations could be found to study. They observed no gag grouper, very few amberjack, and fewer than 10 scamp grouper. They also observed that the destruction of Oculina, first noted in 1975, continued. They could not be certain, though, since no measurements had been taken back in the mid-70s. Because the large coral bases that once existed were reduced to finger-sized rubble, some mechanical disturbance, such as trawls, were likely responsible. This was a "clarion call" to attempt to reestablish a viable coral habitat, and it was then that the SAFMC made habitat restoration of the banks a top priority.

The targeting of spawning areas for fishing and the loss of habitat lead to overfishing. This is especially true for species with complex social behaviors, such as groupers, because these behaviors may be disrupted. This, in turn, disrupts the ability of grouper aggregations to maintain the optimum balance of males and females necessary for a sustainable population. If fishing pressure becomes too intense, the aggregations are eliminated. Once eliminated, they may take a very long time to reestablish themselves,

depending on the species.

The loss of the Oculina coral heads and heavy fishing pressure contribute to the dramatic decrease in gag grouper on Oculina Bank, the most important reef-fish fishery for both commercial and recreational fishers throughout the South Atlantic region (North Carolina to south Florida). From late January to early April, spawning aggregations assemble offshore, on shelf-edge reefs about 200-400 ft deep. Here, they "assess" the proportion of males and females that make up the spawning aggregation. This triggers a percentage of individuals to alter their sex at the beginning of the spawning period to achieve an approximately 80% female/20% male balance. This transformation from female to male takes about one to three months.

Scientists reason that by the end of the spawning period, many, but not all, females leave the spawning aggregation and move to a much wider area inshore, leaving the males, most large females, and those females that are transitioning to males in a smaller aggregation on the shelf-edge reef where spawning took place. Because a higher percentage of males are now part of the aggregation, fishermen's catch of males increases near the end of the spawning season and trails off as the next spawning season approaches.

This suggests that fewer males will be available at the onset of the next spawning season, as observed in catch data. With fewer males to fertilize the females' eggs, the likelihood of inbreeding and the loss of genetic diversity increases. Fewer males could also challenge a traditional fisheries-management principle that assumes all eggs that can be fertilized are fertilized.

Research Questions

What marine scientists want to know is how fishing on spawning aggregations causes a rapid depletion of fish stocks, and whether year-round closures of traditional spawning areas can reverse the demographic distortion and depletion of fish stocks. To make these inquiries, scientists need areas that are closed to fishing. Unfortunately, fishing seems to have continued well after Oculina Bank was closed to bottom fishing in 1994 (based on personal observations).

One of our main objectives on this cruise is to determine if fish populations are increasing in the portion of Oculina Bank that is closed to fishing (the EORR). To accomplish this, we must compare fish abundance both within (protected) and outside (unprotected) of the EORR using manned submersibles and remotely operated vehicles. We cannot, however, evaluate the condition of gag and scamp spawning aggregations on this expedition, because they occur in late winter and early spring. We can, however, evaluate the relative fish abundance.

Observations from the Clelia Submersible

We surveyed Jeff's Reef at the southern end of the EORR today and were pleased to find many gag and scamp, apparently resident on the reef, including males of both species. This is an encouraging observation, because in 1995, a year after the EORR was established, we saw no gag and fewer than 10 scamp. When we revisit this reef during spawning season, we expect to find active spawning aggregations of both species.

We also observed other species of grouper, including snowy grouper, rock hind, speckled hind, and red grouper, within the EORR. Speckled hind are of special significance because their populations have been so severely reduced that they are now candidates for threatened species status. At this point we have not made comparisons in similar habitats both within and outside of the EORR, but we plan to make those comparisons during the remainder of the cruise, or in future expeditions.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.