By Beth Crumley, Assistant Historian, U.S. Coast Guard

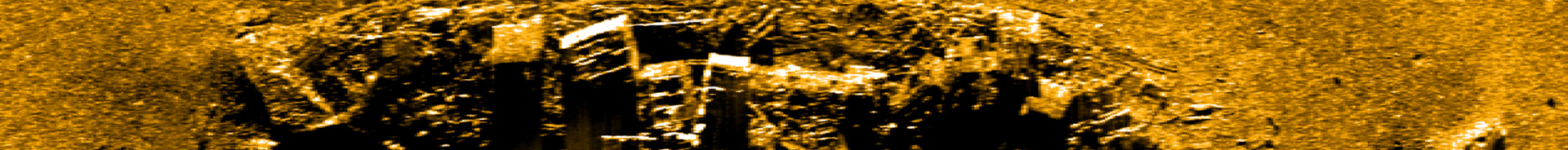

Approaching the starboard side of the bow of the shipwreck. Image courtesy of NOAA/MITech. Download largest image (jpg, 174 kb).

In 2019, the U.S. Coast Guard and NOAA partnered to search for the iconic ship Bear. Built in 1873-74 as a three-masted steam barkentine sealer, Bear was acquired by the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in 1884. After serving for 41 years in the Arctic, the ship was sold, and eventually joined the Byrd expedition to the Antarctic for both the 1933 and 1939 expeditions. Upon her return in 1941 to the U.S. Navy, she was refit and assigned to the Greenland Patrol. Bear is nothing short of iconic, significant to both Coast Guard history, as well as American history.

On September 14, 2019, the Medium Endurance Cutter Bear took in lines and slipped from her mooring in Boston. Pulling away from the dock, the cutter turned eastward under gray, overcast skies. The 270-foot vessel passed the skyline of the city, bound for the North Atlantic. This 2019 expedition was drastically different from the cutter’s usual law enforcement and counter-narcotics operations. Bear was the platform chosen to undertake the search for her namesake.

I was very fortunate to be chosen to participate in this search. While I had been to sea before, it was as an historian. In 2019, I was assigned to the NOAA survey team. It was incredibly challenging, but equally thrilling. Over the course of two weeks, 24-hour operations were conducted using side scan sonar. Armed with years of historical research, the team was able to narrow the search parameters, and a promising site was located. We returned to port excited by our success and the prospects of another mission to further explore the site. That follow-on mission was originally scheduled for April 2020, using the ocean-going buoy tender Oak, but was postponed. Rescheduled for September, it was again postponed, due to COVID-19 concerns and a very active hurricane season.

Finally, after 19 long months, on June 10, 2021, a new team boarded U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sycamore. That team included NOAA’s Dr. Brad Barr and marine archeologist Maddie Roth, as well as Evan and MaryAnn Kovacs, Brendan Carney, David Ullman, and a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) team from Marine Imaging Technologies. These team members, with help from Sycamore’s very capable crew, turned the 225-foot, ocean-going buoy tender into a research vessel. There were cable lines to run, computers and camera gear to set up. Because the dry lab was set up in the area where the crew usually works on buoys, it is a small and confined space and thus quickly filled with control towers and computer monitors. Screens on the bridge and mess deck were run with live feed. A light chandelier was constructed and the ROV, named Pixel, readied.

After transit to the wreck site, preparations began for launch. The USBL (Ultra Short Baseline Positioning System), used to calculate a subsea position, was lowered into the water. With the help of Sycamore’s deck crew and crane, the chandelier was lowered, and Pixel slipped beneath the waves.

Now submerged, the lights came up. The cameras went live. The images on the screen appeared absolutely magical. At first, there was a beautiful blue water column, which progressively darkened, and finally, a pebbled seafloor. The cameras caught glimpses of life—anemones, their pink and blue tentacles waving like flowers in a breeze, and fish such as cod, flounder, wolf fish. Finally, pieces of wreckage lying on the seafloor became visible.

I cannot convey the excitement, or the wonder I felt. Other members of the team are experienced at this. I am not. To see this on live feed was MESMERIZING. Then rising from the seabed, a dark shape…a bow, its form graceful. Despite the obvious damage, it is still impressive. Layers of planking can be seen, its steel sheathing clearly visible…

Have we found Bear?

Drafted June 16, 2021; published June 23, 2021