By William H. Thiesen, Ph.D.

Coast Guard Atlantic Area Historian

Originally posted in The Long Blue Line

If you are subjected to miserable discomforts, or even if you suffer, it must be regarded as all right and simply a part of life; like sailors, you must never dwell too much on the dangers or sufferings, lest others question your courage.

In the above quote, Revenue Cutter Service officer David Henry Jarvis wrote in his diary journaling the Overland Relief Expedition, considered one of the most spectacular rescues in the history of the Arctic. Jarvis’s exploits in Alaska and the Arctic Circle made him one of the Service’s best-known officers of the famous Bering Sea Patrol.

Born in Berlin, Maryland, in 1862, David Jarvis received an appointment to the Revenue Cutter Service School of Instruction, in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Starting school only a few years after its establishment, he came under the tutelage of famed cutterman John Henriques. Henriques had sailed the high seas for 40 years, rounded treacherous Cape Horn, and commanded cutters in Alaska before founding the School of Instruction, forerunner of the Coast Guard Academy. Under Henriques’ guidance, Jarvis learned shiphandling skills, seafaring, and the responsibilities of command.

Jarvis’s early career gave no indication that he would become famous for his Arctic exploits. In 1883, he received a third lieutenant’s commission and assignment to the cutter Hamilton, stationed at Philadelphia. During his time on board Hamilton, the cutter’s cruising area extended from New Jersey to North Carolina, including the Delaware Bay. Two years later, Jarvis transferred from the Hamilton to the Civil War-era cutter gunboat E.A. Stevens based in New Bern, North Carolina.

In 1888, Jarvis received orders to the Pacific Coast where he would spend the remainder of his Service career. In early April, he reported on board the cutter Bear, stationed in San Francisco. On board Bear, Jarvis made the first of many cruises on the Bering Sea Patrol. Each of the patrols covered between 15,000 and 20,000 miles with heavy seas and bone-chilling temperatures. Conditions on these patrols were harsh, dangerous, and deadly—a fact demonstrated by Bear crewmembers buried at Dutch Harbor, in the Aleutian Islands. Bering Sea veterans had a ditty to describe these conditions: “Hear the rattle of the windlass as our anchor comes aweigh; we are bound to old Point Barrow and we make our start today; keep a tight hold on your dinner, for outside the South Wind blows; and unless you’re a sailor, you’ll be throwing up your toes.”

After returning from his first Bering Sea Patrol, the Service transferred Jarvis to the cutter Thomas Corwin, also based in San Francisco. For the next few years, Jarvis served on board the Corwin and San Francisco based cutter Richard Rush, before returning to the Bear in 1891.

During Jarvis’s years on board Bear, neither roads or railroads existed in Alaska, so cutters were the primary federal presence in the territory. Cutters had to adopt an exhaustive list of missions, becoming true interagency support vessels for Alaska. During Jarvis’s return cruise in 1891, Bear secured witnesses for a murder case; transported Alaska’s governor on a tour of Alaska’s islands; shipped a U.S. Geological Survey team to Mount Saint Elias; carried lumber and supplies for school construction in remote locations and the Arctic; delivered teachers to their assignments; carried mail for the U.S. Postal Service; enforced seal hunting laws in the Pribilof Islands; supported a Coast and Geodetic Survey team; provided medical relief to native populations; served life-saving and rescue missions; and enforced federal law throughout the waters and shorelines of Alaska.

On that same cruise, Jarvis was on hand when Bear imported reindeer from Siberia to starving native peoples in Alaska. Native Alaskans relied heavily on whaling and fishing when the territory came under U.S. control. However, after foreign whaling, fishing and sealing vessels entered Alaskan waters, fish and game began to diminish, causing large-scale malnutrition and starvation in native villages and settlements. To solve the problem, Bear delivered 16 live deer and hundreds of bags of native moss for feed from Siberia to the Aleutian Islands to test the animals’ ability to travel by sea. In her 1892 cruise, Bear brought over a larger shipment of the animals to the Seward Peninsula and set up a reindeer station at Port Clarence. In the coming years, cutters transported thousands of reindeer. In the early 20th century, the Alaskan reindeer herds would total 600,000 head with 13,000 native Alaskans relying on the herds for life’s essentials.

Bering Sea cutters patrolled the waters of the Pribilof Islands, seizing seal poaching vessels of all nationalities. And, during Jarvis’s 1892 cruise, Bear was on hand when military action nearly erupted between the United States and Great Britain over seizure of British sealing vessels. Oversight of seal hunting laws proved the cutters’ law enforcement value and the Revenue Cutter Service eventually took responsibility for enforcing all Alaskan game laws. Also, during Jarvis’s cruises on Bear, the cutter supported the regular “court cruise,” in which she transported judges, public defenders, court clerks, and marshals for criminal cases located around Alaska.

During Jarvis’s Bering Sea patrols, the Service’s humanitarian support of Alaska not only included better nutrition for native communities, but control of illegal liquor distribution used to exploit native people in the Alaska Territory. Native people called Jarvis’s Bear “Omiak puck pechuck tonika” or “the fire canoe with no whiskey.” The Service’s humanitarian support of Alaska was assistance on a sweeping scale, but the cutters assigned to Alaska also aided individuals on the maritime frontier. As one Coast Guard historian wrote about Bear: “In assisting private persons, neither class, race, nor creed made any difference to the Bear; degree of stress was the sole controlling factor.”

During his time on board Bear, Jarvis had become a Bering Sea veteran, with extensive geographic and cultural knowledge of the Alaskan frontier including fluency in the native languages. By 1896, he had reached the senior officer rank of first lieutenant and served as Bear’s executive officer. That same year, famed Bering Sea captain Michael “Hell Roarin’ Mike” Healy ended 10 years as commanding officer of the Bear. The veteran cutterman described the pressures of serving as captain on a Bering Sea cutter: “to stand for forty hours on the bridge of the Bear, wet, cold and hungry, hemmed in by impenetrable masses of fog, tortured by uncertainty, and the good ship plunging and contending with ice seas in an unknown ocean.”

By 1897, Captain Francis Tuttle took command of Bear. Later that year, eight whaling ships became trapped in pack ice near Point Barrow, Alaska. Concerned that the ships’ 265 crewmembers would starve to death, the whaling companies appealed to President William McKinley to send a relief expedition. In 1884, Bear had led the U.S. Navy’s famous Greeley Relief Expedition to save the starving men of an Arctic expedition led by Army lieutenant Adolphus Greeley. Now under orders from President McKinley, Bear would lead a second major rescue mission into the Arctic.

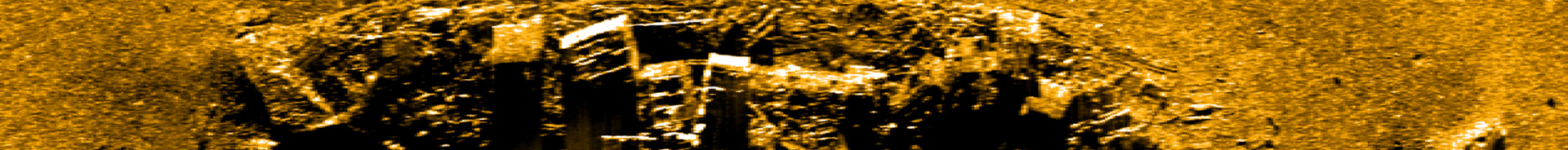

In November 1897, soon after completing her annual Alaskan cruise, Bear took on supplies at Port Townsend, Washington, and returned to the coast of Alaska. This would be the largest of several mass rescues of American whalers undertaken by Bear during the heyday of Arctic whaling. And, it was the first time before modern icebreakers that a ship risked sailing above the Arctic Circle during the harsh Alaskan winter. To lead the so-called Overland Relief Expedition, Captain Tuttle placed executive officer Jarvis in charge of a rescue team that included Second Lieutenant Ellsworth Bertholf, U.S. Public Health Service Surgeon Samuel Call, and three enlisted men.

With no chance of the cutter pushing through the thick ice to Point Barrow, Capt. Tuttle put the party ashore at Cape Vancouver, Alaska. He tasked the men with driving a herd of the Service’s newly introduced reindeer to the whaling ships. Using sleds pulled by dogs and reindeer, the expedition set out on snowshoes on Thursday, December 16, 1897. So began a rescue effort unusual in the annals of Coast Guard history. It would require Jarvis and his men to cover 1,500 miles over snow and ice rather than the usual Service elements of coastal waters and open ocean.

On Tuesday, March 29, 1898, after 99 days of endless struggle against the elements, the relief party completed the journey. The expedition delivered 382 reindeer to the starving whalers with no loss of human life. When Jarvis and Dr. Call finally arrived at Barrow, Jarvis recounted that:

when we greeted some of the officers of the wrecked vessels, whom we knew, they were stunned; it was some time before they could realize that we were flesh and blood. Some looked off to the south to see if there was not a ship in sight, and others wanted to know if we had come up in a balloon. Had we not been so well known, I think they would have doubted that we really did come in from the outside world.

In his journal, Lt. Jarvis later recounted the final days of the expedition: “Though the mercury was -30 degrees, I was wet through with perspiration from the violence of the work. Our sleds were racked and broken, our dogs played out, and we ourselves scarcely able to move, when we finally reached the cape [at Pt. Barrow] . . . .” For the Overland Expedition, President McKinley recommended Jarvis, as well as Bertholf and Call, for a specially struck Congressional Gold Medal. In the aftermath of the expedition and the concurrent Spanish-American War, McKinley wrote to Congress:

The year just closed has been fruitful of noble achievements in the field of war, and while I have commended to your consideration the names of heroes who have shed luster upon the American name in valorous contests and battles by land and sea, it is no less my pleasure to invite your attention to a victory of peace.

After returning home from the Overland Expedition, Jarvis assumed command of Bear, as would Ellsworth Bertholf, who in 1915 rose through the ranks to become the first commandant of the modern Coast Guard. Later, while still an officer, Jarvis became a special government agent at Nome, Alaska, and served there when a smallpox epidemic struck the community. In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt assigned Jarvis as customs collector for the District of Alaska. In 1905, Jarvis was promoted to captain and that same year, he retired from the Service after a nearly 25-year career. After his retirement, he pursued private business ventures in Alaska, including the development of copper districts and the building of a railroad by a syndicate of New York bankers. During this period, President Roosevelt also offered Jarvis the governorship of Alaska. Captain David Jarvis died in 1911, six years after leaving the Revenue Cutter Service.

David Henry Jarvis spent the majority of his career in the waters of Alaska. During that time, he was associated with famous cutters, such as the Corwin, Rush, and Bear, and Service luminaries such as Henriques, Healy and Bertholf. Jarvis became an important figure in his own right not only in the history of the Service, but also in the settlement of Alaska. A high-endurance Coast Guard cutter has borne his name, as does Mount Jarvis in Alaska’s Wrangell Mountains. Today, the Service awards the Captain David H. Jarvis Leadership Award every year to a Coast Guard officer who demonstrates outstanding leadership skills and motivates and inspires personnel to strive for excellence. Jarvis was a member of the long blue line and his memory lives on in the history and heritage of the U.S. Coast Guard and the State of Alaska.