September 20-30, 2020

In 2020, researchers at Oregon State University explored six previously unvisited methane seeps along the Cascadia Margin to understand their microbial diversity and associated ecosystem services they provide. Analysis of samples collected during the expedition has led to the discovery of fungi species new to science. This discovery, coupled with information about the diversity of animals and chemical compounds found at seep habitats, provides insight into how these methane seeps may shape our future.

A microbial mat at a methane seep in the Cascadia Margin of the Pacific Ocean. Image courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust Cruise NA095. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

The ocean bottom may seem banal to the untrained eye: an open expanse of brown, seemingly squishy seafloor marked only by glistening white clams and the occasional bubble creeping from the substrate. But a closer look reveals a forest-floor’s worth of diversity that relies on the interaction between methane – the gas seeping from the crust to form those innocuous bubbles – and microbes, which are microscopic, single-celled organisms. While microbes feast on energy-producing methane, diverse fauna thrive in the food-rich environment that the microbes foster. These habitats, known as methane seeps, are a hub of life and biodiversity in the deep ocean.

As we’ve increased our understanding of methane seeps, humans have identified ways that these unique habitats might support our own species. Like humans, microbes communicate with one another, and they create signals using chemical compounds. We’ve long recognized that terrestrial microbes can produce compounds that have pharmaceutical or technological properties; the fungus Penicillium rubens has been used to create the antibiotic penicillin for many decades. Although microbes have been documented at methane seeps, their biopharmaceutical and biotechnological properties remain largely unexplored.

During the Gradients of Blue Economic Seep Resources expedition, researchers at Oregon State University sought to expand our understanding of deep-ocean methane seeps and their potential uses by documenting microbial biodiversity throughout the Cascadia Margin, located offshore of the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary of the Pacific Ocean. During a research expedition to the Cascadia Margin in 2020, the project team discovered six previously unvisited seeps by using multibeam sonar that allowed them to map and detect underwater plumes of methane. They then used a remotely operated vehicle to visually survey the seep sites and collect samples for later analysis.

Dive sites of remotely operated vehicle Hercules in the Pacific Ocean during Ocean Exploration Trust Cruise NA095. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Two of the newly explored seeps represented opposites of the geological time spectrum: while one site consisted of a gigantic microbial mat and soft sediments characteristic of early successional stages, massive piles of hard, carbonate rock made from methane-eating microbes indicated that another seep may have taken hundreds or thousands of years to form. The project team collected samples of water, sediment cores, rocks, and myriad organisms including sponges, brittle stars, and chemosynthetic clams from the seeps that they discovered.

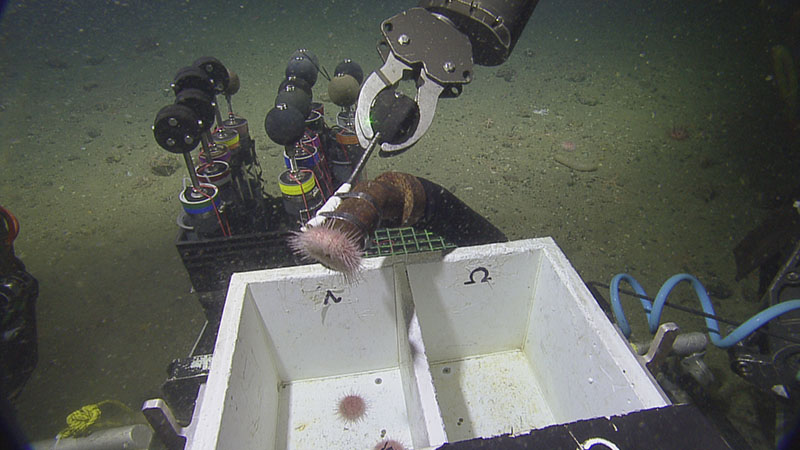

Researchers direct the manipulator arms of remotely operated vehicle Hercules to collect a suction sample of a sea urchin at one of the methane seep sites visited during the Gradients of Blue Economic Seep Resources expedition. Image courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust Cruise NA095. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Upon returning from their expedition, the researchers extracted DNA from their sediment samples and began to characterize microbial communities. Among their discoveries was that of fungi species new to science; more than 55% of fungi sampled could not be identified to the phylum level. Fungi are among the most prolific taxa with regard to antimicrobial compound production.

The breadth of fungal diversity discovered, coupled with the team’s biopharmaceutical and biotechnological compound analysis that showed present and divergent compounds throughout the seeps, has generated questions about what microbial compounds and other ecosystem services may exist in these highly prolific, deepwater ecosystems.

Chemosynthetic, vesicomyid clams and a colorful fish (likely Sebastolobus sp.) present at a methane seep in the Cascadia Margin of the Pacific Ocean explored during the Gradients of Blue Economic Seep Resources expedition. Image courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust Cruise NA095. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Published June 29, 2023