By Lila Ardor Bellucci, Graduate Student, Oregon State University

September 29, 2020

Part of the fun in exploring never-before-seen methane seeps is that it’s hard to predict what you’re going to find. Even across similar ocean depths and latitudes, individual seep sites can vary dramatically in the way they look and function and in the animals and microbes that live there. One reason is because seeps can be thought of as having lifetimes and can look very different at different phases in their Iives. During two dives while exploring the Cascadia Margin, we were lucky to find seeps in two opposite ends of these phases, often called “successional stages.”

Carbonate rocks, created as a byproduct of methane being eaten by microbes, provide a home for many animals from octopods to mushroom corals. You can also see in the fissures between the rock the expansive microbial mats and clam beds; this fauna is living on a shallow dusting of mud overlying even more carbonate rock. Video courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (mp4, 46.6 MB).

During one of our first 1,000-meter (3,280-foot) deep methane seep remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dives, we were surprised to come across massive piles of carbonate rock, looming above ROV Hercules like dark towers. This type of rock is formed by the methane-eating reaction that Archaea and Bacteria living at cold seeps carry out. Carbonate rocks of this size could have taken hundreds or even thousands of years to form! This told us that the seep must have been during a later successional stage in its life. Although we still came across living clam beds, often found at methane seeps, we did not see any of the bubbling that is common at some younger seep sites. Because we saw no bubbling in the multibeam sonar over the seep site and only knew about bubbling there from past sonar data, there was always a risk that we would descend and not be able to find the seep. In this case, the risk paid off and we found what must once have been a very active seep.

When we see bubble plumes like this we know there will be methane leaking from the seafloor; however, we never know what that is going to look like and on this particular site we were met with an amazingly expansive microbial mat. Image courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (jpg, 445 KB).

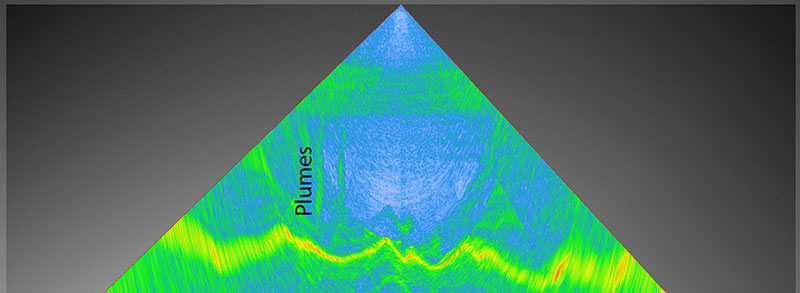

Our next discovery was even more unexpected. On our way to the late successional stage seep site, our multibeam mapping team noticed a large bubble plume in the sonar data, again about 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) deep. Although we hadn’t initially planned on it, we decided to take a chance and investigate further. As we descended with the ROVs, we picked up the acoustic signals of bubbling from over 100 meters (328 feet) off the seafloor. When we arrived at the bottom, we were greeted by one of the largest microbial mats any of us had ever seen.

This 50-meter (16-foot) diameter microbial mat was incredibly soft and covered by both bacteria as well as thousands and thousands of tiny snails, some of which were even covered by bacteria themselves. This soft and expansive mat is a “young” habitat in contrast to the expansive carbonate discussed earlier in this log. Pretty amazing that these two seeps are both at the same depth and close together...and yet entirely different. Video courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (mp4, 44 MB).

As we navigated around its edge to gain our bearings, we realized that it seemed to go on forever, covering at least 50 square meters. As we explored its interior, we found numerous bubble plumes on the northern edge of dense white and gray bacterial mats, filled with small tube worms and surrounded by extensive clam beds. This was a textbook young seep, in an early successional stage and (to our delight!) still soft and perfect for taking sediment core samples. At older sites, taking cores can be difficult because of those carbonate rocks that form, blocking the core tube as we try to push it in.

We collect sediment cores to look at the biodiversity and try to better understand how seeps fit in the ocean ecosystem. This video is sped up four times. Video courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (mp4, 44.5 MB).

Although studying individual seep sites really well can be very valuable, it’s also important to study a broad range of seeps when trying to gain a better understanding of them. As this tale of two seeps shows, even nearby seeps can be very different, each telling us part of a larger deep-sea story. Unexpected discoveries like this help us to shape our understanding of a seep’s lifetime, thereby providing valuable guidance for future research.