By Dr. Kerry McPhail, Oregon State University

October 13, 2020

Our team from Oregon State University (OSU) recently completed a research expedition aboard the Exploration Vessel Nautilus, which was shared with a team from Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary (OCNMS). The OSU team’s target was methane seeps, signaled most often by sudden patches of glinting white clam shells or bacterial mats shimmering against the otherwise gray-brown of thick ocean sediments that stretched into the darkness.

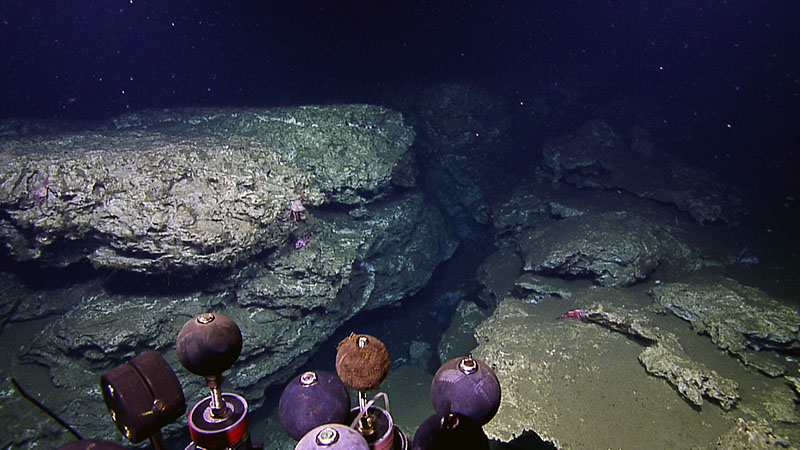

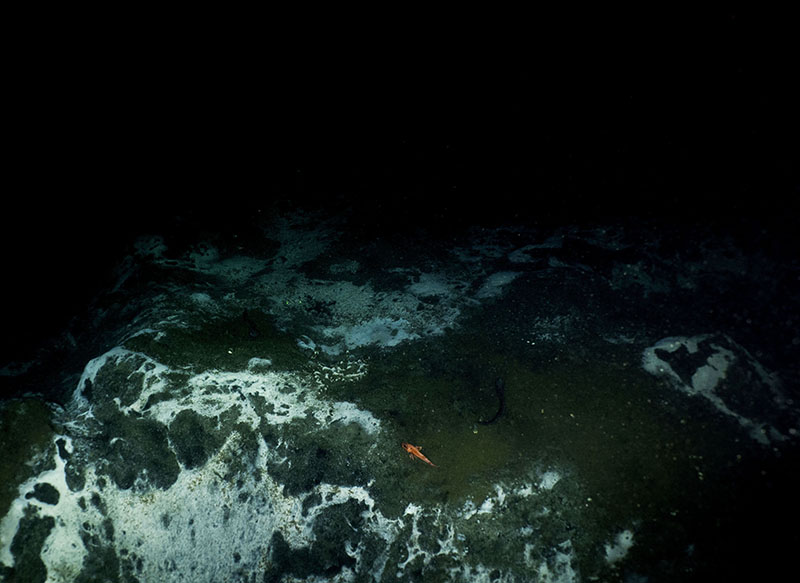

Two ‘seep dives’ were particularly spectacular, one revealing an expansive rocky outcrop of carbonate deposits with a diversity of marine animals, and the other revealing impressive methane bubble plumes and extensive white bacterial mats that in some places looked like giant pancakes. These surreal scenes captured by the cameras of remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Hercules at around 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) depth were captivating, although dramatically different to the colorful shallow marine reefs visited most often by medicinal chemists interested in marine natural products.

At one site, we found thick bacterial mats with small worm tubes sticking out of them. One of the mats was so dense it looked as if we were flying over a pancake on the seafloor. Video courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (mp4, 74.6 MB).

At these deep methane seeps, in the absence of light, with very little oxygen, and at atmospheric pressure a hundred times greater than that on land, some microbes ‘feed’ on methane, while others consume hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, or minerals to derive energy for themselves and other deep-sea creatures by ‘chemosynthesis.’ This distinct metabolism is enabled by altered, pressure-tolerant lipid membranes and enzymes, which invites the idea that natural product molecules made by these microbes may also have unique molecular structures and biological functions. What has that got to do with biopharmaceutical discovery?

In contrast to the above video, other sites have carbonate formations created from prolonged seepage fueling bacterial mats. Image courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

It is only in the last 20 years that scientists established that marine bacteria in deep-ocean sediments, and also housed in sponges and corals, make natural product compounds useful for pharmaceutical discovery. Land-based plants and intertidal marine algae have been used as traditional medicines for thousands of years and are a rich source of diverse natural product compounds that have been developed as pharmaceutical drugs in Western medicine since the late 1800s, when Aspirin was developed by Bayer. Since that time, plants, fungi, soil bacteria, and marine reef animals such as sponges and tunicates have provided many widely used antibiotics and medicines for cancer and other chronic diseases.

Areas like this microbial community on the seafloor are epicenters of microbial interaction, and based on what we learned from exploring nature on land, may hold the potential for great discoveries. Neosporin antibiotic ointment is made up of the three antibiotics neomycin, polymyxin and bacitracin, all from soil bacteria; the original statin drug was discovered from a fungus; the cancer drug Taxol was originally isolated from the Pacific Yew tree; and the metastatic breast cancer drug Halaven is derived from a marine sponge. What help can methane seeps provide for diseases of today and tomorrow? Image courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (jpg, 5.3 MB).

The overarching realization is that different living organisms adapted to living in different habitats have evolved different abilities to produce a variety of natural product compounds for chemical defense or communication in their specific environments. Thus, exploring diverse and unusual environments that harbor biologically diverse organisms is a rational strategy for finding new natural product compounds that may have unprecedented functions and cellular targets relevant to combating human diseases. Indeed, shrinking global biological diversity and the increasing global health challenge of antibiotic and cancer drug resistance lends urgency to gaining an understanding of the little known biological diversity in the deep ocean and its untapped potential for human health and economy.