By Matt Breece, Post-Doctoral Researcher, University of Delaware

July 22, 2018

I think I speak for most of the scientists, and even ship’s crew, when I say that this is a trip we have been looking forward to for a long time. Our task here in Kiska is ironically circular. We are using some of the best technology available, with some very innovative minds pushing the future, to explore the past. I have caught myself many times thinking we are taking the same steps that sailors and soldiers took decades ago to defend our country with the best technology and innovative minds available to them.

Kiska Island is a beautiful place, but it is not very hospitable, even in the mildest months. We are fully outfitted with great foul weather gear and the newest technology, but it is still cold and wet, and we spend a lot of time fixing problems and making improvements. The men who made camp on this island 75 years ago had the same things we have, the best in foul weather gear and the newest technology, and spent much of their time fixing problems and making improvements.

The heroes that came before us were much, much tougher and more brave than I. They came to fight a war, and many lost their lives, but still, they made this place home for a while, which makes the two weeks we are here seem like the blink of an eye. These thoughts are very humbling, as they should be. I am a scientist here by choice, and tonight we had ice cream and watched a movie after dinner, a much different life in very different circumstances. I am writing this not to compare our abilities or circumstance here on Kiska, but to compare our spirit of adventure. They were here to defend, we are here to learn.

Despite the circumstances they were here in, I like to think they were as excited and amazed to be here as we are. Kiska Harbor is stunning with its rolling green landscapes, waterfalls, and volcanos; contrasted by gray skies, fog, stunning white clouds, and occasional sunshine creating explosions of color.

While much of our work has focused on Kiska Harbor, the other day we found ourselves across the island surveying targets. When we were wrapping up and prepping for transit back to the harbor, the buzz began. I think it started as a joke (as most great ideas do), but quickly took hold and the next thing we knew half of the crew was racing the ship back to the harbor by taking the most direct path, over land, and on foot. We only had three miles to go and the ship had hours of steaming, how close of a race could this be? Eight of us made the beach around 3:00 PM and we quickly started doing the math, wondering if we would make dinner on the other side.

The adventure begins, hiking through a valley on the north side of Kiska Island. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 920 KB).

There are no forests or even trees on the island, the vegetation consists of grasses, mosses, ferns, and bogs. It surprisingly reminds me of a coastal saltmarsh back home on the Chesapeake or Delaware Bay, but this was on land, and not just flat land, hillsides, old roads, and tent pads—it didn’t matter—it was consumed by knee deep vegetation on top of ankle deep mud. We hiked for about an hour across a valley before we started up the hillside headed for a saddle which would lead us to the harbor and dinner. Our party of eight quickly became four parties of two with explorers seeking out the best route or hoping to stumble upon something not seen for 75 years.

As we approached the saddle, Kyle stopped to take a drone flight to capture the stunning view of both the Bering Sea and Pacific Ocean. A quick “I hope it’s not too windy,” turned into an “OH NO, I’M LOSING COMMS” as the drone raced uncontrollably towards the harbor in the 30 knot wind tunnel. Kyle sprinted over the saddle to try to secure a connection and I grabbed up our belongings and followed in tow.

When I got over the hill, I found Kyle and Andy looking from screen to sky try to determine where the drone was and what its camera was seeing. After five minutes, that felt like an hour, Kyle was able to get us in the drone’s view and then fly low, out of the wind, to safety. As we sighed in relief and laughed about our escapade, Eric T. stood up from behind a mound of vegetation and alerted us to an aircraft engine that he and Andy were investigating before the drone tried to run away.

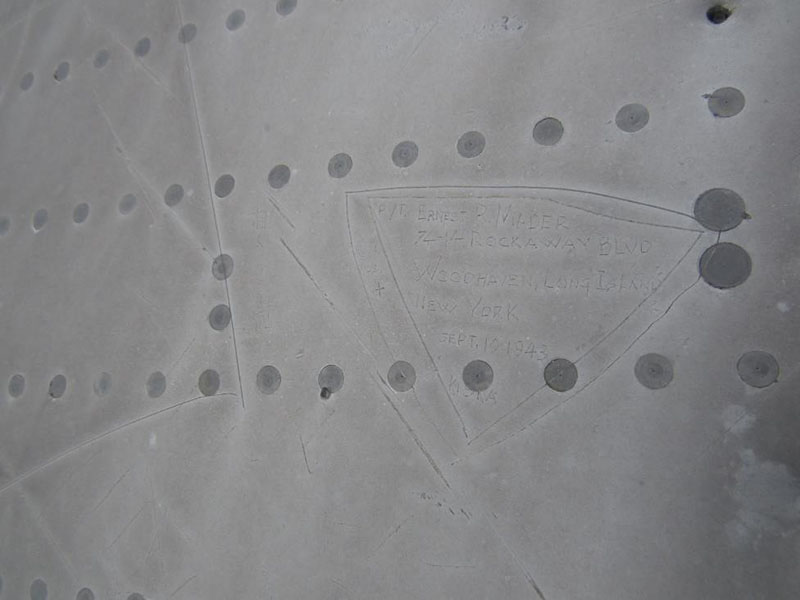

The engine wasn’t the only item on that saddle; we also spotted a large piece of sheet metal on the hillside which we obviously had to investigate further. Upon arrival, we immediately knew it was a plane wing from a U.S. bomber. It was rolled out ALCOA 0.051” aluminum. We are here on Kiska looking for planes, and while this obviously wasn’t an unknown wreck, it was still a really cool find for us. Immediately we started looking for more clues and quickly found some scratching on the wing from previous visitors. From far away, it appeared to be graffiti, but looking closer, we discovered it was actually from the soldiers on the island, some Japanese and some American. I am unable to interpret the Japanese, but the American scratching not only gave the date they visited, but full names, ranks, and home addresses.

Scratching from U.S. soldiers on the bomber wing not long after the U.S. took back over Kiska Island in 1943. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 185 KB).

Our soldiers sat here on this very same wing, which means they hiked this same mountain, saw these same stunning views come and go with the fog, got soaked to the bone by the same rains, and mourned the same loss of these airmen fighting for everyone back home. After exploring the debris field some more and imagining the steps taken by those before us, we continued our hike down to Kiska Harbor, making it in time to watch the Norseman II round North Head and come out from under the fog to pick us up for dinner.

R/V Norseman II coming out of the fog into Kiska Harbor to pick us up for dinner after our hike across the Island. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 841 KB).

We made that hike with a couple bottles of water, cameras, candy bars, and a drone. The soldiers had to make it with canteens, MREs, and rifles. They did it for us, and we are doing it to learn about them. There are MIAs still on this battlefield, and our hope is to honor them for their sacrifice and bring peace to their families after all this time.