By Mike Jilka, Marine Technician, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

July 18, 2018

When I was asked to participate in an upcoming project in Kiska, Alaska, I thought to myself, “Wow! An opportunity to visit Alaska, a place I have always wanted to visit. Now all I need to find out is the location of Kiska Island.” Far west they say, along the Bering Sea near the end of the Aleutian Islands chain.

As I remember the wild stories of my good friend who has been a commercial fisherman for the last 25 years, my concern for a cold, rough, and stormy ocean and home of the toughest fishermen, like those seen in the TV series “The Deadliest Catch,” triggered a sense of nervous tension and the beginning of a battle of butterflies in my stomach. The deeper I dive into the topic of World War II’s Aleutian Islands Campaign, I begin to realize the difficulty of conducting an expedition in such an extreme environment, so close to the end of the Earth. I wonder how thick do my socks need to be? Will my only old winter coat be warm enough? Do stores in my southern California town sell a rain jacket good enough? Will I become sea sick and worthless?

The view from my airplane window: snowy mountains and icy flows. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 227 KB).

With my flights scheduled, suitcases overpacked with clothing options, months of planning and preparations to shipping a sea container of science and field gear, and a confident feeling that my dry suit SCUBA dive training will pay off, I jumped on the opportunity and volunteered to rendezvous and load the research vessel in Dutch Harbor, Unalaska. Greeted by stunning sights of endless mountains with snow and icy flows from my airplane window, I landed in a small fishing town. Cold rain, cold wind, and a muscle-tensing chilly gust rushed up my jacket as I wondered how people actually live here, in a place that’s already so cold in the summer. “This is summer here?” I thought, “I'm so glad it’s not winter.”

The view overlooking Dutch Harbor. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 158 KB).

We saw several bald eagles soaring over the beautiful landscape. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 150 KB).

With zero cell phone signal and an airport rental car with running windshield wipers, a colleague and I made our way around the wet roads of Dutch Harbor in search of the vessel we planned to load and spend the next the couple of weeks aboard. A day after meeting the crew, organizing numerous pelican cases of equipment, running cables around the ship, and securing everything for transit, we decided to discover for ourselves how Dutch Harbor became one of the top-ranked fishing ports after such a terrible war had taken place. We drove up to picturesque cliffs and peaks overlooking the harbor and its shorelines scattered with hundreds of refrigerator-style shipping containers and crab pots dive-bombed by bald eagles soaring the beautiful landscape, while the evidence of old military structures maintained their presence.

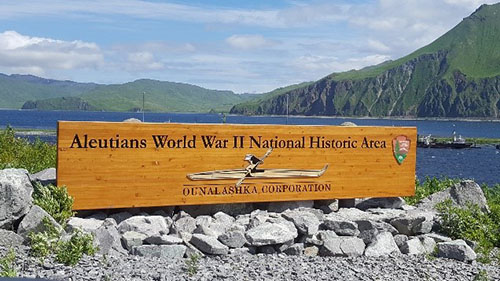

Later we arrived at the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area Visitor Center which had exhibits and photos that documented the war which took place in the coldest and harshest oceanic weather conditions. Inside the building, I unzipped my jacket as I browsed the museum and looked through the blurry wet windows at the tall grass blowing outside, again recognizing the symbolism and reality of the true sacrifice that all the troops made here. During this moment of remembrance, I stared at the displayed artifacts of war, and while the sight through the blurred museum glass faded away, I imagined looking through another view out a research vessel’s porthole, splashing along an Aleutian voyage to the Island of Kiska, where the search for missing heroes and closure for families will begin.

The Aleutian World War II National Historic Area. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 235 KB).

We’ve been at Kiska since the evening of July 12th. Our ship's gunnels finally drained from the seawater accumulated by the tireless rough seas. Hot brewed coffee is constantly flowing and the cool breeze enters the back door as the crew and research team prepare missions. Safety is always first as full personal protective equipment and rain gear is worn on the back deck.

Working as a team, a crane picks an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) and deploys it over the side, tag line is taught, crane boom is out, swells sway against the ship, long boat poles keep the AUV from slamming the ship hull as it is lowered into the water, buoyancy is checked, and portable radios are alerting the captain in the bridge. Once the quick release is yanked, the crane operator raises the hook, and the AUV is off, turning to port away from the ship. Hurray! Another survey is underway with the hope of gathering the data to document the wrecked ships and planes that represent the cultural resources here in Kiska.

Dense fog rolling down the hillsides calm the waters inside the harbor. Image courtesy of the Kiska: Alaska's Underwater Battlefield expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 156 KB).

It's 10:30 PM, still plenty of daylight, and two pairs of divers begin gearing up to SCUBA dive on a target found with sonar data. I head below into the ship's heated lazarette where our foul weather gear and dry suits are hung. Wearing thick undergarments under a dry suit, I gracefully jump into the water, fins first, trying to prevent any splashing water from entering my neoprene hood. I begin to drop beneath the water surface, feeling a snowy freeze on my face and lips. After a few minutes, the thrill and excitement of the dive counterbalance the thought of the chilly 39° Fahrenheit water as we proceed to the depth of a wreck lost for over 75 years.

After a late night snack, while our vessel anchors up for the night, I lay in my bunk reviewing a few photos of my exciting day. I stumble across a photo of my family which was emailed from a hot summer Southern California day at the beach. I wiggle my toes, stretch my feet, and smile as I recall the feeling of the hot water shower which followed the coldest summer day I have ever faced.