By Mark Moline, University of Delaware

Kiska Island remains one of the best preserved historic battlefields from World War II (WWII) with no settlement prior to or after the war. While the occupation of the Japanese and United States (US) recapture of the island are well documented on land, the waters around Kiska Island still hide numerous relics from this brief but pivotal battle. With the exception of a brief survey of Kiska harbor in 1989, the region is largely unexplored. In addition to more than a dozen Japanese ships sunk in the harbor, we estimate there are a significant number of downed US aircraft, two Japanese submarines and a section of a US Destroyer in the coastal waters surrounding the island. Documentation of these sites is important historically and culturally as many of these sites are associated with the remains of US service members. Applying new technologies and documentation approaches, we hope to explore and digitally preserve one of the least studied, yet most significant campaigns of WWII.

Whether we will be documenting a ship, a plane, or a submarine on this expedition of the Kiska underwater battlefield, our approach for documenting the sites will be the same. First, it is important to get a larger “view” of the specific site. Because there is battle damage and some of the aircraft hit the water at high speeds, the wreckage is often spread across a significant area and requires this larger perspective. Specifically, we will be using a combination of multibeam sonar from the surface vessel and sidescan sonar from our autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). These high frequency sensors produce high resolution (centimeter scale) acoustic images of the wreckage and surrounding seabed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: High resolution side scan sonar acoustic image of a P-39 aircraft in Papua New Guinea. Image courtesy of Project Recover . Download larger version (jpg, 316 KB).

These sensors provide the orientation of the entire site and often helps us reconstruct the last moments of the event. After examining these acoustic site maps, we will use a number of techniques to visually inspect and document the site. Visual images will be collected from downward-looking cameras mounted on the same AUVs that carry the sidescan sonars. If the sites are accessible using open SCUBA (depths shallower than 150 feet), photos/video of the wrecks will be taken by divers as well as measurements and hand-drawn maps (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Archaeologists use measuring tapes and underwater cameras to record and document a WWII aircraft site in Papua New Guinea. Image courtesy of Project Recover . Download larger version (jpg, 3.2 MB).

If the visibility is low due to silt and sediment in the water, divers will also carry imaging sonars, much like ultrasounds for fetal examinations, to both locate the site and also produce a complete acoustic image of the site at high resolution. If the depths are deeper than 150 feet or there is a need to spend an extended time at the site, we will use a small working class remotely operated vehicle (ROV), which is tethered to the surface for power and piloting. Our ROV is outfitted with video and still cameras as well as sonar to orient the vehicle in case of low visibility conditions. Unlike our divers, who will be using drysuits in the 45⁰ F water, the ROV can be on site for hours, with many trained eyes identifying key features/items and visually documenting the entire site in detail.

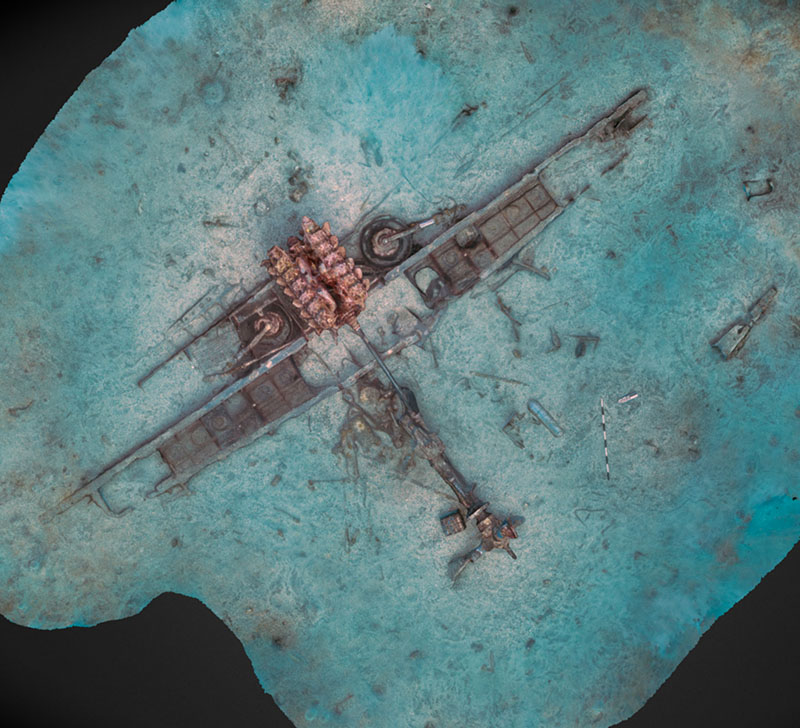

Over the past 75 years, the ocean biology and chemistry dynamics have had a corrosive effect on these historic wreck sites. Depending on the life growing on the wreck, the salinity, pH of the water, the scouring by sand particles, the current speeds, and the type of plastics or metals, the rate of decay of a given site will be different. We will use oceanographic instrumentation around Kiska Island to measure ocean currents, temperature, salinity, pH, and oxygen in the water to assess these environmental conditions and make assessments of the long-term integrity of these underwater sites. We are at an important crossroads in time. These wrecks are not yet lost to the elements and remain largely intact, and at the same moment, advances in technology, imaging and computing specifically, allow us to digitally preserve these historic sites in perpetuity. Images from the downward-looking cameras on the AUVs, diver-held cameras, and cameras/video on the ROV can all be used to digitally reconstruct and preserve these sites. Recent advances in photogrammetry, called stereophotogammetry or structure from motion, use common points in multiple images to reconstruct three-dimensional models of the wreck sites at the resolution of the cameras. Once these models are completed, they can give perspectives of each site from all angles and distances, such as a birds-eye visual image of each site or produce a fly through (diver’s perspective) of the site (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Orthomosaic of a P-39 aircraft in Papua New Guinea. The orthomosiac was created using specialized software that stitches together hundreds of images captured by divers at the site to form a single comprehensive image. Image courtesy of Project Recover . Download larger version (jpg, 2 MB).

This virtual preservation can also be used in the future to assess further change at a given site or for planning in a future investigation. All of the sonar, visual, and oceanographic information from this expedition will be gathered and used to fully document each of the sites in the Kiska underwater battlefield and provided to NOAA and other government agencies. In the case of sites that are associated with US service members missing in action (MIA) from WWII, separate reports will be provided to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency to inform their mission of MIA recovery.