By Andrew Pietruszka, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Like the bombing of Pearl Harbor and America’s entrance into World War II, the Aleutian Campaign came suddenly when undetected carrier-based Japanese planes bombed United States (US) installations at Dutch Harbor on June 3rd 1942. Three days later, Japanese forces landed on Kiska and Attu, two remote islands in the far western reaches of the Aleutian chain. On Kiska Island, the initial invasion force of 550 men was quickly reinforced to sustain occupation. A naval installation comprised of a submarine base, sea plane base, and protected anchorage for ships was established at Kiska Harbor while the Japanese Imperial Army garrisoned 3,500 men on its base at the head of Gertrude Cove. Infrastructure, including a system of roads and telegraph wires, were quickly erected linking forces throughout the island. The Japanese also heavily fortified the island with an impressive array of anti-aircraft weapons. The largest concentration of these encircled Kiska Harbor at North Head, South Head, and Little Kiska and wreaked havoc on low level US bombing missions. At the height of occupation, Japanese forces on the island totaled more than 7,200.

The American response to the Japanese invasion was immediate. On June 11th, 1942, a combined force of US Army and Navy aircraft unleashed a near continuous three-day bombing campaign, known as the “Kiska Blitz”, in which the US Navy alone reportedly dropped 65,000 tons of bombs (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The 474-feet long Japanese transport ship Nisan Maru sinking in the middle of Kiska Harbor after it was stuck by bombs dropped by the US 11th Air force on 18 June 1942. Two other Japanese ships are visible in the harbor nearby. Image courtesy of NARA RG80G 11686. Download larger version (jpg, 2.5 MB).

Though formidable, the offensive failed to unseat the Japanese, and thus began a protracted bombing campaign and blockade strategy that remained in effect until US and Canadian forces retook Kiska Island 15 months later.

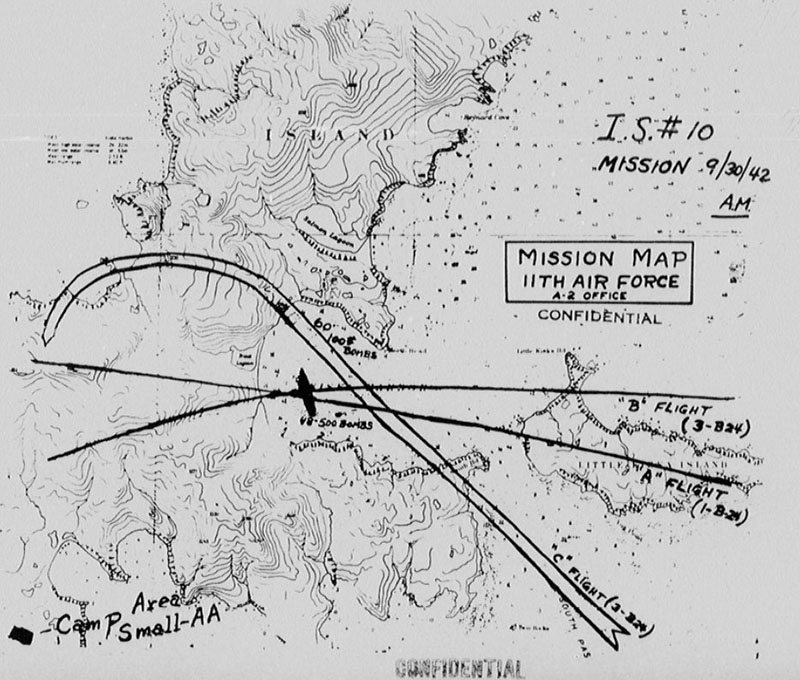

How the war was fought by opposing sides during the Aleutian campaign, and, in particular, the battle for Kiska Island, stands in stark contrast. For the Japanese, the campaign was a land-based occupation with supporting naval operations and little effective air support. The American campaign was largely confined to the air. Between June11th 1942 and August 14th 1943, the US led forces carried out 601 air missions, totaling 3,609 individual sorties, dropping seven million pounds of bombs on Japanese targets (Figure 2 and 3). The Japanese in contrast never had more than 14 effective planes at any time.

Figure 2: Mission map detailing the September 30th 1942 morning attack by B-24 bombers of the US 11th Air Force against Kiska Island. Image courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA). Download larger version (jpg, 2.4 MB).

Figure 3: A North American B-25 Mitchell Glides over an American destroyer after taking off from Unmak Island for a raid on the Japanese base at Kiska. Image courtesy of NARA RG80G 11686. Download larger version (jpg, 414 KB).

Strategically, the campaign also served very different purposes; for the Japanese, it was two-fold. First, it served as a diversionary tactic. Coinciding with the planned invasion of Midway Island it was meant to draw US forces, particularly carrier support, north strengthening the Japanese offensive in the South Pacific. Secondly, it was a defensive maneuver. The Japanese concerted their main force on Kiska, where they believed their occupation and fortification would prevent America’s advancement along the Aleutian chain and the establishment of remote bases from which the US could conduct strikes against the Japanese homeland. Consequently, the occupation of American soil provided a psychological win, and with only a minimum force, tied up valuable US and Canadian resources that otherwise could have been deployed elsewhere. At its maximum, the combined Japanese garrison for the entirety of the Aleutian Islands was about 8,500 men; the combined US force assembled to expel them in August 1943 was 35,000 (Russell 2008:72).

The thought of Japanese forces occupying American soil was simply unacceptable for the Americans, and immediately orders were issued from Washington to “FIGHT BACK. PUSH THE ENEMY INTO THE SEA. GET KISKA.” And although it would take 15 months to accomplish, US forces did eventually succeed in expelling Japanese forces from Kiska and the Aleutian Islands (Figure 4).

Figure 4: US soldiers inspect Japanese midget subs left behind after the US retook Kiska Island. Image courtesy of NARA RG80G 80363. Download larger version (jpg, 3.8 MB).

The successful campaign gave the US their first theater wide victory over Japan and left them in sole possession of a “chain of unsinkable aircraft carriers” from which the Eleventh Air Force could strike the Kuriles as the northern arm of the air force pincer encircling the Japanese Empire.