By Chuck Meide, Director of the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program - Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program

July 18, 2014

Already at work before the sunrise, Sam is working to configure one of our backup laptops as the new magnetometer laptop, after a hard drive failure in our previous computer. Image courtesy of Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565 Expedition, NOAA-OER/St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 375 KB).

We are not really at our best until the coffee is ready. Left to right: Dr. Sam Turner, Brian McNamara, and Brendan Burke. Image courtesy of Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565 Expedition, NOAA-OER/St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 366 KB).

Today we woke up to some problems. Actually we went to bed with the problems, and of course they were there facing us when we crawled out of our bunks and cots at 5:45 am.

Now, problems are typical on any marine remote sensing survey. Getting three computers to “talk to” a satellite positioning system and to high-tech sonar and magnetometry devices, while on a rocking boat in the hot, humid, and salty environment of the open ocean can be a Herculean feat. Overcoming problems is the norm. In fact, it really is a rarity when everything works the first time and keeps on working.

Brendan and Sam prepare to deploy the magnetometer. Sam is holding the mag, a lightweight Explorer model made by Marine Magnetics. Image courtesy of Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565 Expedition, NOAA-OER/St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 364 KB).

Our nightly ritual, after a hard day’s work collecting data, is to back up the results of the survey to an external hard drive, and then to an additional laptop. Last night we almost faced disaster.

After a really successful day, which saw 14 hours straight of successful marine survey (from 7:35 am to 9:36 pm) to complete 10 survey lines or 50 nautical miles of scanning, we started backing up the data. The sidescan and subbottom acoustic data copied without a problem, but our mag laptop, which has been dedicated to magnetometer survey for the last several years, suddenly found itself on Death’s door, knocking loudly.

When it first froze up, we weren’t especially concerned, until after an attempted re-boot it came up with the famed “blue screen of death.” It took five additional attempts to re-boot before the machine started up, albeit with an error notification indicating a problem with its hard drive. Needless to say, we immediately began the data transfer and were visibly relieved when our data was safely loaded on another machine. We collapsed in our bunks knowing that in the morning we’d have to configure one of our backup laptops to serve as the mag computer.

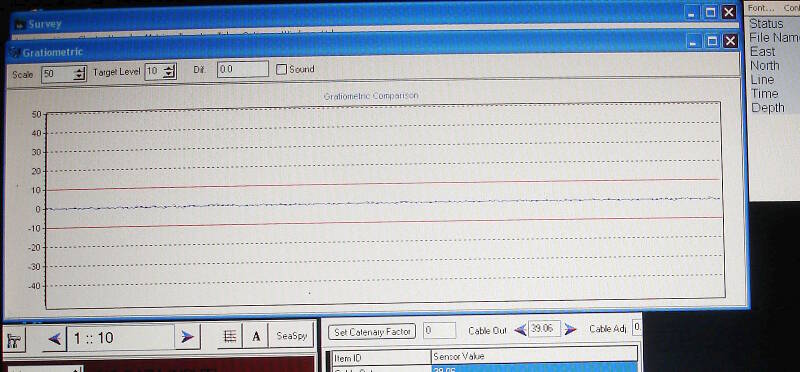

This is a close-up view of the magnetometer computer screen. It shows a graphic display much like an EKG machine in a hospital. The flatline in this image indicates there is no ferrous material (steel or iron) underneath the magnetometer sensor head. Image courtesy of Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565 Expedition, NOAA-OER/St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 294 KB).

As I mentioned before, this kind of thing is pretty typical, and we came prepared, having brought with us no less than six additional laptop computers. This would be the third backup that would be put into service on the trip, and there’s still two days to go!

As soon as the coffee was hot, Sam dedicated himself to getting the Hypack survey software installed on the machine and making sure all of the devices were attached and working properly. He had to download a required driver but the new mag laptop was ready by 7:30 am.

Of course, by that time, the subbottom profiler laptop was acting up, not recognizing its hardware, and that took another 20 minutes to resolve. And then we found out that the newly configured magnetometer laptop was not recognizing the signal from the magnetometer. This time it was Brendan who solved the problem and by 8:15 am, we had begun to survey our next line, Lane 24. Each survey lane is five nautical miles long, parallel to shore, and spaced 20 meters apart.

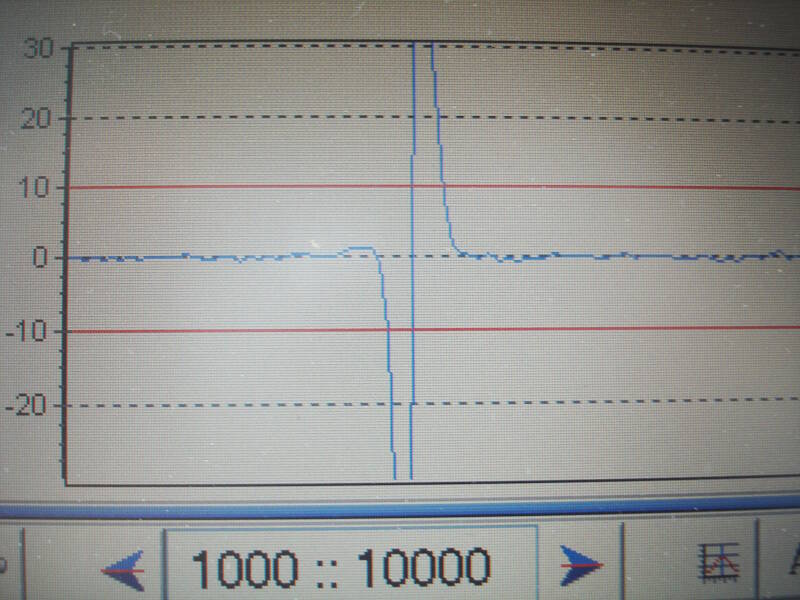

This is a classic example of a magnetic anomaly. The flatline suddenly dips, dropping more than 30 gammas below ambient magnetism, and then shoots upwards before returning to normal magnetism. Image courtesy of Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565 Expedition, NOAA-OER/St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 432 KB).

The magnetometer is really our primary instrument of discovery. Unlike the sonar devices, it does not send out a signal but instead measures the ambient magnetism of the Earth. We have it set to take a reading every second when towed behind the boat, so it records a lot of readings over a single, five-mile long survey lane, which takes us about an hour and a half to complete at a speed of four knots.

Each magnetic reading, which is expressed in gammas, is tied to a precise geographic location recorded by the Global Positioning System (GPS). The GPS determines its location by interpreting signals beamed down from satellites in space.

When analyzing data from both devices, we can identify areas of the seafloor which contain iron or steel, and know exactly where they are located on the surface of the Earth, with an accuracy of less than one meter.

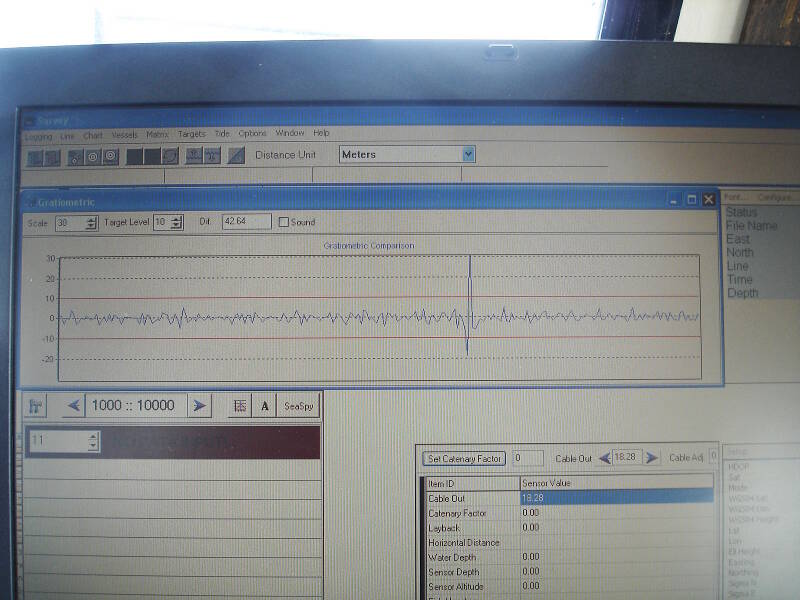

Another magnetic anomaly, also in the form of a dipole, visible in the line of data on Lane 30. The background noise in this lane is much more pronounced and erratic, so we don’t have the nice, quiet flat line as seen in the previous survey lane. This can be due to the direction of the boat in a particular sea state. But the magnetic hit is still very visible. Image courtesy of Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565 Expedition, NOAA-OER/St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 418 KB).

The flatline in the image above means that our data is very “smooth,” or consistent with very little variation. Any iron embedded in the seafloor would cause a variation in the signal, which might look like a spike or a wavy line. With data this smooth, any small anomaly will be obvious. We don’t always get such consistent readings. If the seas are very rough, for example, the mag doesn’t travel as evenly in the water and its readings will be more erratic.

The image to the right shows a magnetic anomaly that we saw in Lane 29. The downward spike, followed by an upward spike, is known as a “dipole.” Other anomaly forms are a monopole, which is a single spike only upward or downward, or a multi-component anomaly which contains more than one dipole. This was one of the first anomalies we observed during the survey, and we were very excited to see it.

Captain Brendan Burke pilots the Roper along a survey lane while Dr. Sam Turner monitors the magnetometer display. Image courtesy of Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565 Expedition, NOAA-OER/St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 275 KB).

Things got even more exciting when we encountered another similar reading on an adjacent line. Multiple anomalies spread across different survey lanes suggest a significant scatter or concentration of iron that might indicate a historic shipwreck!

We are so excited about our potential finds that even when we see the marine forecast, which calls for worsening seas, we remain enthusiastic. As it turns out we feel the need to end the survey early, as it becomes clear that we can’t safely stay out overnight with the increasing seas. So once again, we head into Ponce Inlet and to a berth at the City Marina courtesy of the City of New Smyrna Beach.

Even though the weather has forced us to lose a few hours, we are all enthusiastic about our potential shipwreck hits, and it is the topic of conversation for the night. All in all, it was a pretty good day. Despite delays due to computer problems, and being forced out of the survey area by weather, we still managed to complete seven lanes, and we also saw two anomalies that could represent a shipwreck. Not a bad day, really.