By Chuck Meide, Expedition Principal Investigator - Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program

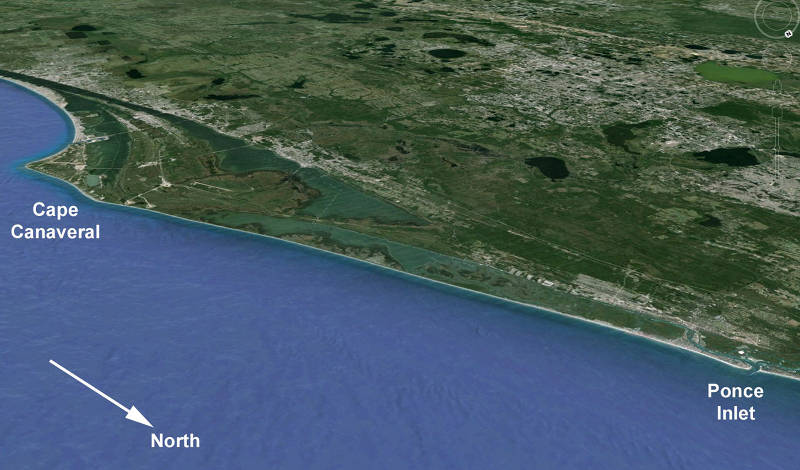

The Armstrong Site and the French Fleet search area are located in the Canaveral National Seashore, between Cape Canaveral and Ponce Inlet. Image courtesy of the Search for the Lost French Fleet of 1565. Download larger version (jpg, 250 KB).

During the winter of 1970-1971, a group of Central Florida relic hunters discovered an archaeological site on the western or inland shore of the outer barrier island in what is now Canaveral National Seashore. Over the next several months, the group explored the site and the surrounding area, locating two more related sites, all within 1.3 kilometers of each other.

Iron artifacts recovered from the Armstrong Site that were salvaged from wreckage and modified by 1565 shipwreck survivors. At left, there are four examples of ship’s fastener heads which have been cut from their shanks by saw or chisel. Many examples were found, and they for the most part represent debitage from tool making using a forge and tools. Some could have been meant to form hammer heads by insertion into the striking face of a wooden mallet. At right are partially intact ship’s spikes. Each displays clear evidence of using a forge to heat and then tools such as saws, hammers, chisels, anvil, and clamps to remove stock iron for use in constructing new tools. Image courtesy of John de Bry. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Using metal detectors, the treasure hunters dug up a variety of objects of European origin, including large numbers of iron ship’s spikes, some jewelry, and numerous Spanish and French coins dating to the 16th century.

Though the group disbanded after 1972, one of them, Douglas Armstrong, became increasingly interested in the artifacts he had retained. After renewed study, he realized the significance of the artifacts, and speculated that they might be associated with Ribault’s fleet.

Almost 20 years after the discovery of these sites, he contacted the National Park Service, who by that time were custodians of the property, to report the finds and share the information he had gathered.

Examples of jewelry recovered from the 1565 French shipwreck survivor camps. Left: A bead fashioned from a rolled silver coin, a Spanish Charles and Johanna four real believed to be from the late series (1542-1572). It was recovered from the Silver Palm Site. Center: One of four thin sheet gold pendants recovered, believed to have been cut from a hammered French gold demi-ecu coin. Right: A silver wedge chiseled from a late series Charles and Johanna four real coin (1542-1572), intended to be a pendant or possibly a manicuring tool. It was chiseled along the famed “Plus Ultra” inscription, which may indicate French rather than Indian modification, and the edges were carefully filed. Image courtesy of John de Bry. Download larger version (jpg, 3.8 MB).

The initial site has been named the Armstrong Site, after Douglas Armstrong, who was the appointed record keeper for the metal detectorists. The other sites discovered by Armstrong and his companions were the Pistol Point Site and the Silver Palm Site. These sites are all in the same area, a short distance from the beach, on the estuarine lagoon side of the outer barrier island, located in lands occupied by the Surruque Timucuan peoples during the 1565 shipwreck event.

Armstrong believed that the recovered artifacts indicated these sites were encampments inhabited by survivors from the French shipwrecks. Three months of systematic archaeological excavations undertaken at the Armstrong Site by the National Park Service’s Southeastern Archeological Center (SEAC) in 1990 and 1995 confirmed this interpretation.

The most compelling evidence that this site was occupied by Frenchmen, as opposed to only Indians who may have salvaged shipwrecked material themselves, came in the form of ship’s fasteners, many of which had been modified using knowledge and technology available only to European craftsmen.Armstrong in the 1970s and SEAC archaeologists in the 1990s found numerous examples of iron spikes cut or otherwise altered through the use of the tremendous heat of a forge, a capability that was beyond the technical knowledge of the Surruque or other Native Floridians.

It seems clear these spikes were being modified to make tools needed for survival or trade, including hammerheads, points, awls, chisels, and drills. In addition to tool making, these metalworkers were also making jewelry, almost certainly for trade, as they appear in styles (pendants, beads, plummets, etc., many fashioned from reworked French coins) that would have been appealing to the local Indians.

Contemporary European ceramics, including stoneware originating in Normandy; clothing adornments (buttons and a hat pin); and fragments of weaponry were also unearthed. Also, the numerous French and Spanish coins recovered over the years provide a terminus post quem of at least 1552.

The evidence of French survivors living and working at these sites is beyond a reasonable doubt. What is not clear is whether or not the French survivors were actually living with the Surruque, or were simply occupying abandoned sites previously used by Indians. Either way, they must have been interacting with the natives to some degree, and were likely providing tools, weapons, and jewelry on a regular basis from the raw materials salvaged from nearby shipwrecks, in return for food and protection from Spanish authorities.

Examples of jewelry recovered from the 1565 French shipwreck survivor camps. Left: A bead fashioned from a rolled silver coin, a Spanish Charles and Johanna four real believed to be from the late series (1542-1572). It was recovered from the Silver Palm Site. Center: One of four thin sheet gold pendants recovered, believed to have been cut from a hammered French gold demi-ecu coin. Right: A silver wedge chiseled from a late series Charles and Johanna four real coin (1542-1572), intended to be a pendant or possibly a manicuring tool. It was chiseled along the famed “Plus Ultra” inscription, which may indicate French rather than Indian modification, and the edges were carefully filed. Image courtesy of John de Bry. Download larger version (jpg, 3.2 MB).

These survivor camp sites represent an important clue to the location of the French shipwrecks. There is often a close geographic correlation between the location of shipwreck survivor camps and the shipwreck site itself. This has been demonstrated archaeologically in Florida, by campsites associated with the wrecks from the Spanish 1715 treasure fleet, and also by numerous examples in Australia.

Archaeologist Martin Gibbs has noted that even if a survivor campsite does not represent the initial landing place, but later movement to a more suitable location, proximity to the original wreck remains an important factor. The shipwreck was an immediate source of familiar subsistence and useful materials, and it seems unlikely that survivors would have moved too far away from such a useful resource.