By Chuck Meide, Expedition Principal Investigator - Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program

Every Florida student knows the story of the French Huguenots who came to settle Florida under the command of Jean Ribault. The first settlers who came to America seeking religious freedom, the French at Fort Caroline in present-day Jacksonville would suffer a dramatic and bloody end with the arrival of their bitter enemy, a Spanish Catholic force under command of Pedro Menéndez.

The showdown between the rival powers played out under a sudden and devastating storm, which wrecked the four largest French galleons and resulted in the massacre of the shipwrecked survivor sby Menéndez. It was thus the Spanish that founded the first and oldest city in America, St. Augustine, in 1565.

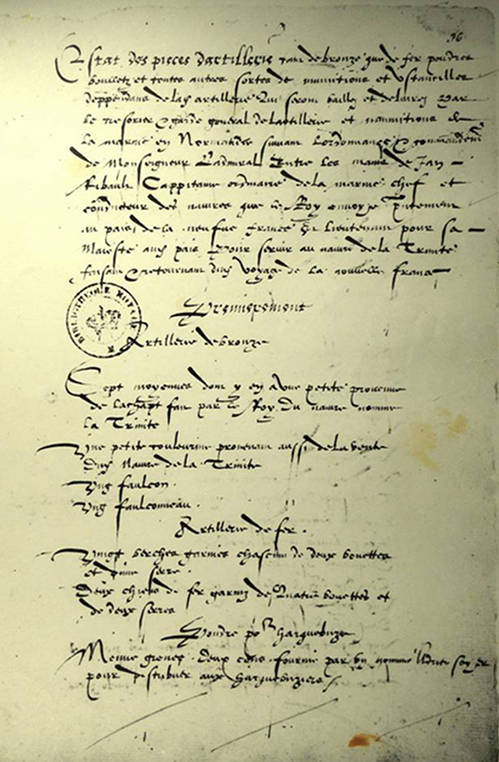

First page of the commissioning of the Trinité, 21 May 1565. This document lists supplies and equipment on board for the Florida expedition. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France ( BnF), français 21544. Download image (jpg, 75 KB).

The year 2015 will mark the 450th anniversary of these formative events, when this Florida story will become an American story and capture the national imagination. In anticipation of this anniversary celebration, the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP), the research arm of the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum, has partnered with the State of Florida, the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, the National Park Service, and the Institute of Maritime History launched the search for the lost French Fleet, aided by research from the Center for Historical Archaeology.

The focal point for this expedition is a five-mile stretch of ocean off the Canaveral National Seashore. This search area is adjacent to a series of terrestrial archaeological sites which have been identified as 1565 French shipwreck survivor camps. Featuring mid-16th-century French coins and other artifacts, along with salvaged ship fittings modified to make survival tools, it is logical to assume that these sites are in the immediate vicinity of one or more of the wrecks offshore.

We know from historic documents, including cargo manifests and eyewitness accounts, that Ribault’s flagship La Trinité and the other three wrecked ships were fully loaded with supplies and never had a chance to discharge their cargos. This means that the ships should display prominent magnetic signatures and likely feature a wide range of well-preserved material culture intended for the colonization effort.

During the late summer of 2014, our team of maritime archaeologists operated the research vessel Roper on a seven-day cruise to survey a five-mile long stretch of the Atlantic Ocean using geophysical instruments including a marine magnetometer, sidescan sonar, and sub-bottom profiler. This magnetic and acoustic data was then be analyzed by an international team of scientists in order to identify potential shipwreck targets.

Following the data analysis, Roper returned to the survey area for a 12-day expedition to conduct diving operations in order to physically inspect these targets, in hopes of locating and identifying the remains of one or more vessels from the French fleet.

We expected that most of these targets are buried, which means that our divers had to explore beneath the seafloor sediments using hydraulic probes or dredges in order to identify the source of magnetic or acoustic signatures. Artifacts encountered during target testing, depending on their nature and size, were temporarily recovered for documentation and archaeological analysis before being returned to their original locations within the seafloor.

The historical and archaeological significance of these ships cannot be overestimated. Any one of them, if discovered, would constitute the oldest French shipwreck, and indeed the only 16th-century French shipwreck, in the New World.

Since none were ever unloaded at Fort Caroline, all of the supplies and equipment intended for the fledgling colony could potentially be preserved under sand and sea. Thus, the ships would serve as a veritable time capsule that could contribute unparalleled insights into the earliest French colonization attempt in North America and the first group of settlers seeking religious freedom in America.