By Chuck Meide, Expedition Principal Investigator - Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program

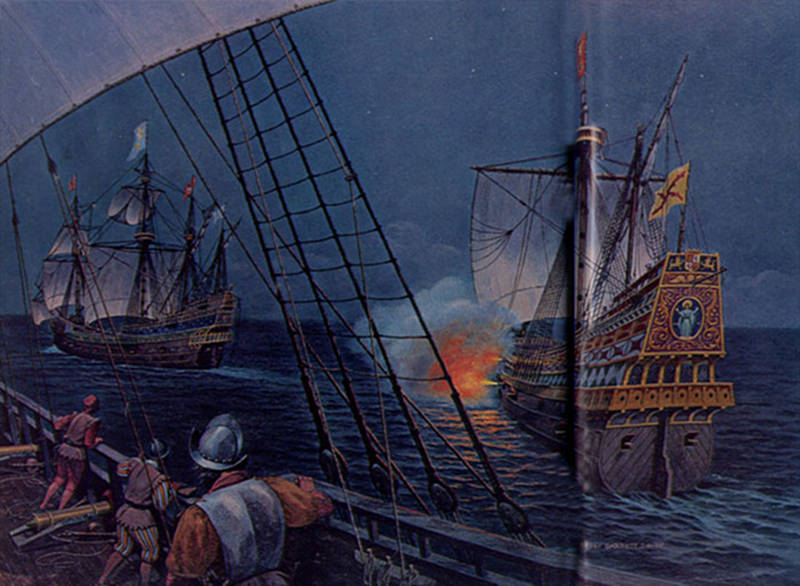

The Spanish and French fleets encountered each other off the River of May and exchanged words, threats, and cannon fire. The French fleet cut their anchor lines to make their escape. When Menéndez saw that Ribault’s troops were already disembarked, he retreated to the next inlet to the south to fortify a defensive position. Painting by Henry Garrett Smith, from National Geographic, February 1966, Vol. 129, No. 2, pp. 206-7. Download image (jpg, 88 KB).

(Review Historical Background Part I: French Colonization in Florida, 1562-1565)

Upon his release from prison in 1564, sea captain Jean Ribault was commissioned to lead the relief mission to Florida. Ribault’s fleet consisted of seven ships loaded with armament and munitions, supplies, livestock, 500 soldiers, and as many as 500 more seamen and colonists.

The nemesis of the French colony, the Spaniard Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, would arrive with his own fleet off the coast of Florida by the time Ribault anchored off the River of May. Menéndez was charged not only with establishing a Spanish presence in Florida, but also with driving out the French heretics once and for all. Under his command were five ships and 500 soldiers, 200 sailors, and 100 others.

Menéndez landed at St. Augustine on 8 September 1565 to take formal possession of the land for Spain, and to found what would become the oldest permanently occupied settlement in North America. Painting by Stanley Meltzoff, from National Geographic, February 1966, Vol. 129, No. 2, pp. 198-9. Download image (jpg, 115 KB).

The stage was set for a fast-moving endgame on 4 September, when Menéndez’ fleet arrived off the River of May. Ribault’s three smaller ships had been discharging their troops and cargos and were light enough to have already crossed the bar at the river’s mouth. His four larger ships were still anchored offshore.

The two fleets identified themselves verbally. When the great Spanish galleass San Pelayo attempted to board the French flagship La Trinité, the French vessels cut their anchor lines and made a fast escape, amid Spanish cannon fire. The Spaniards could not effectively pursue, as their ships’ rigging had been damaged by storm action. Menéndez retreated southward to the next inlet to establish a base of operations at what would become St. Augustine.

On 7 September 1565, a Spanish force disembarked and began digging a temporary defensive entrenchment. The following day, with great ceremony, Menéndez landed and formally founded St. Augustine. He also decided to partially unload his damaged flagship San Pelayo, which at 906 tons was too massive to enter the St. Augustine Inlet. Rather, he sent it to Hispaniola instead of keeping it exposed in a position of danger.

Ribault’s fleet was driven south by the relentless winds of the storm. Despite desperate attempts to claw their way into deeper waters, all were shipwrecked. Painting of La Trinité by and courtesy of William Trotter. Painting of La Trinité by and courtesy of William Trotter. Download image (jpg, 91 KB).

Ribault, meanwhile, saw a chance to demolish the Spanish forces before they could fortify themselves. After a hastily assembled council, and against Laudonnière’s objections, Ribalut decided to make a preemptive strike. Taking two days to assemble his forces, and conscripting a portion of Laudonnière’s able-bodied men, he set sail in his four largest ships with a force of 400 soldiers and 200 sailors.

Ribault’s plan almost worked. His fleet surprised the Spanish and almost captured Menéndez, who barely managed to make it across the sandbar. Ribault’s ships were too large to follow at low tide, but instead sailed south to search for San Pelayo, which had departed only hours before.

It was the following day that the fateful storm struck. Either a nor’easter or a true hurricane, the powerful winds drove Ribault’s fleet further south. Despite frantic attempts to claw their way to deeper waters, all the ships were run aground and shipwrecked. Three of the ships were lost in the vicinity of Ponce Inlet, broken to pieces in the surf, while the flagship La Trinité was stranded intact on a sandbar five to ten leagues further south, towards Cape Canaveral.

Menéndez's men braved the storm, marching “more than 15 leagues, more or less, all of it through marshes and desolate places,” sacking Fort Caroline in a surprise attack at dawn on 20 September 1565. Painting by Birney Lettick, from National Geographic, February 1966, Vol. 129, No. 2, pp. 212-3. Download image (jpg, 151 KB).

Now it was Menéndez’s turn for a bold attack. He knew the French ships would not be able to make their way back north, even if they had survived the storm, which was still raging. Leaving a small force to guard St. Augustine, Menéndez and the bulk of his men set out on 18 September on an overland march.

At dawn on 20 September, the Spanish launched a surprise assault, breached the walls, and took Fort Caroline. Around 130 were killed outright, 45 to 60 more (including Laudonnière) escaped, and 50 women, children, and a few men were spared.

After an abortive parley attempt from on board one of Ribault’s smaller vessels (Perle) anchored off the fort, the French sailed in their five remaining vessels downriver to the safety of the river mouth. After consolidating their scattered survivors, a decision was made between Laudonnière and Ribault’s son, Jacques.

On 25 September the three smaller vessels were scuttled, and the two remaining ships of Ribault’s fleet, Perle and Levrière, sailed for France.

Most of the beleaguered French shipwreck survivors surrendered unconditionally, hoping for mercy from Menéndez. He showed none, writing the King: “And I had their hands tied behind them and put them to the knife.” As many as 350 men were executed. Painting by Birney Lettick, from National Geographic, February 1966, Vol. 129, No. 2, pp. 212-3. Download image (jpg, 165 KB).

Menéndez left a garrison at Fort Caroline, which was now renamed Fort San Mateo. He returned triumphantly to the settlement in St. Augustine on 27 September.

The shipwrecked men from Ribault’s fleet, in contrast, were cast upon a hostile shore. They had begun the long march northward back to their fort, which could no longer provide refuge. They had gathered into two separate groups, the southern one consisting of survivors from La Trinité and the northern group from the other ships.

Menéndez met the first group on 29 September, having been notified by local native peoples of Frenchmen assembled at an inlet south of St. Augustine (traditionally believed to be Matanzas Inlet, which was named after the massacre). After learning of the fate of Fort Caroline, the survivors decided to surrender and put themselves at the mercy of Menéndez. He showed little, sparing around a dozen or so and putting as many as 110 to 200 to the sword.

The second group of survivors, along with Ribault, arrived at the same inlet and a similar drama played out on 11 October. Negotiation between the two leaders resulted in unconditional surrender, though this time around half of the total of perhaps 300 decided to take their chances in the wilderness and left Ribault to make their way back south.

Those who surrendered faced a similar fate as the first group. Between 5 and 16 were spared, while between 70 and 150 were killed.

The final act came on 1 November, when Menéndez led an expedition south to locate the final French survivors who had built a fortification on the beach with six cannon salvaged from the wrecked La Trinité. They fled upon the Spaniards’ arrival, though afterwards Menéndez offered safety in return for surrender. He kept his pledge and around 75 were taken prisoner, though around 20 or so refused and took their chances with the Surruque Indians rather than risk Spanish justice.

The French threat completely eliminated, Menéndez focused on fortifying St. Augustine and other locations along the coast to consolidate Spain’s claim to Florida. The last of the French survivors who refused surrender disappeared into the wilderness and into history.