By John de Bry, Expedition Co-Principal Investigator - Center for Historical Archaeology

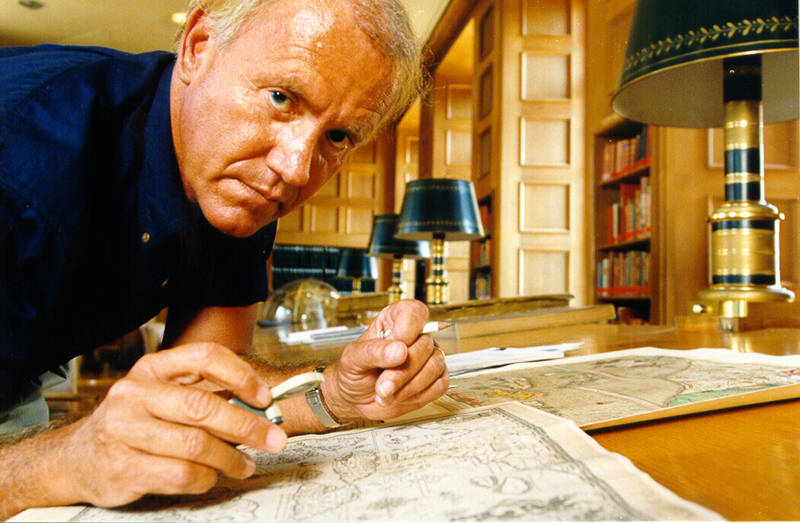

John de Bry in the Map Room of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. Image courtesy of Philippe Eranian/SYGMA. Download larger version (jpg, 932 KB).

Over the last 20 years, I have carried out historical research in French archival repositories related to the French colonization of Florida.

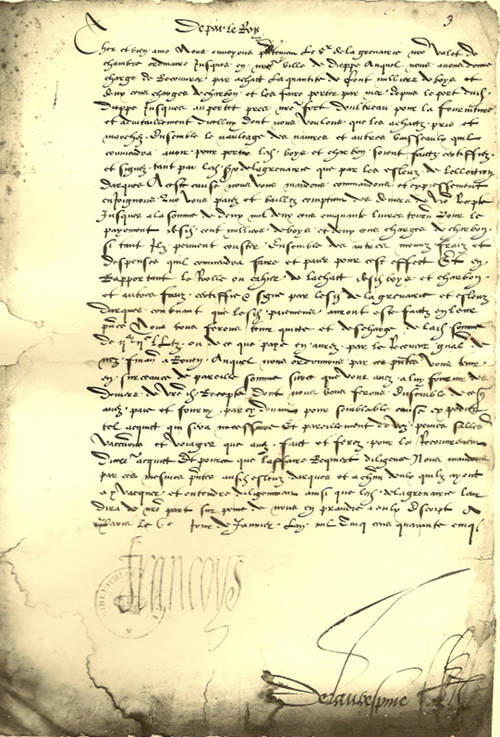

Document bearing the signature of King François I, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 6 October 1545. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), français 21544. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

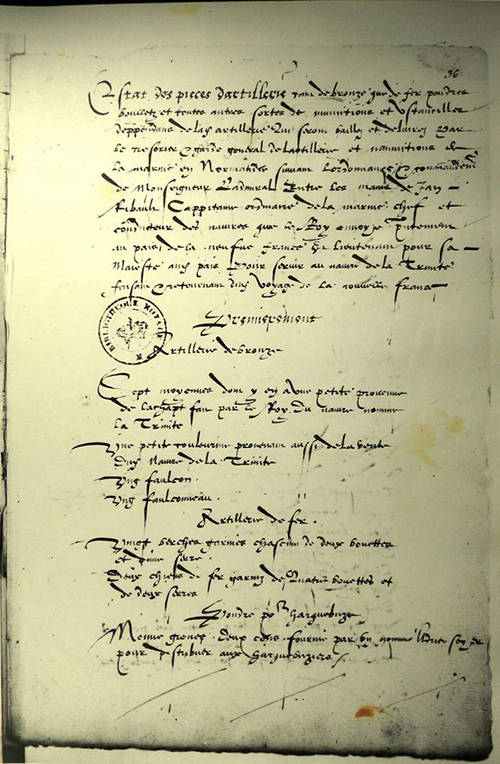

Among the most important documents I have discovered and translated are the commissioning and arming papers pertaining to the fleet in Dieppe (Normandy). Those records are located in a file at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) under BnF, français 21544. They include the commissioning papers for la Trinité, l’Émérillon, la Perle, and la Lévrière. They also include various correspondence signed by King François I (reigned 1515-1547), King Charles IX (reigned 1560-1574), Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, Captain Jean Ribault, Captain Jacques Ribault, Captain Nicolas “Corsette” d’Ornano, and Captain Leblanc.

The earliest document, signed by François I, is dated 1545. Most documents were created in Dieppe in 1565, except for those signed by François I and Charles IX. These were mostly written and signed in St.-Germain-en-Laye, with one signed by Charles IX appearing to have been written in Gemeaux (Côte-d’Or) near Dijon, and dated 1 May 1564.

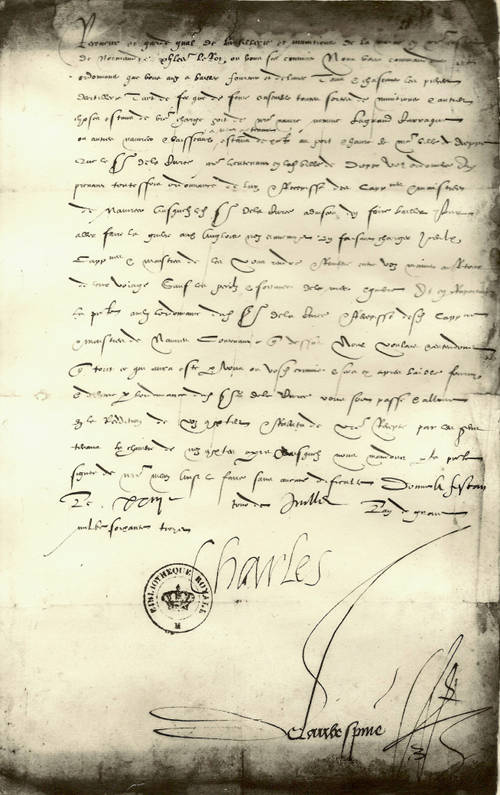

Orders given by King Charles IX to the Guard General of the Artillery of Normandy to provide bronze and iron cannons to ships in the port of Dieppe, signed by the King, July 1563. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), français 21544. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Those documents are very significant for the search for the French Fleet because they contain data about the artillery, other cargos being taken to New France (Florida), and names of crews and would-be colonists. The detailed listing of armament and other equipment made of iron on these ships is indicative of the expected magnetic anomalies that might be recorded during the survey phase of the expedition, and thus can help data analysts segregate potential 1565 French shipwreck targets from other anomalies. The cargos listed in these papers may also help archaeologists positively identify these ships during the diving phase of the expedition.

It is doubtful that more diagnostic archival manuscript documents pertaining to the 1565 Ribault Fleet will be found in the future at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and no construction data for any of the ships in this fleet are known to exist. One document has been recently discovered that may help us better understand the form and construction of the lost French ships, however. French archaeologist Éric Rieth has located a manuscript document dated 7 April 1576 describing the construction of an 80-ton roberge.

At least one of the French fleet wrecked ships was described as a roberge, a ship type about which maritime historians know relatively little about. In this 1576 document, shipwright Guillaume Tuvache, from Honfleur in Normandy, commits himself to build a roberge for Guillaume Champaigne, also from Honfleur. The detailed dimensions given in the document give insight into the construction and appearance of at least one of Ribault’s ships, and may help identify or better understand the remains of any shipwrecks which might be found during the expedition.

First page of the commissioning of the Trinité, 21 May 1565. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), français 21544. Download image (jpg, 145 KB).

It is quite possible that more important documents may be extant in other French repositories. There are also historical records written by the Spanish that are relevant to the search for the French Fleet.

Among most important example of these are the letters that Pedro Menéndez wrote to the Spanish King to inform him of ongoing events in Florida, which have been translated by Eugene Lyon. Menéndez provides many details related to Fort Caroline and the conflict with the French, including a general description of the location of the wrecked French ships which he gained from interrogating shipwreck survivors.

Another particularly valuable Spanish document is a report from a Spanish spy in the French court, which provided a detailed description of Ribault’s fleet before it set sail from France. It is possible that further information pertaining to Fort Caroline and the members of its garrison, as well as the Frenchmen who initially survived the sinking of the French Fleet, may be preserved in Spanish records, awaiting future discovery.

But archival research in any country is a time-consuming and complicated process, and identifying documents pertaining to a particular event is often akin to finding a needle in a haystack. Continued archival research will resume after the close of fieldwork, especially if one or more of the French shipwrecks are discovered and promises to expand our understanding of the French Fleet and the conflict and colonization in Florida.