By Verena Tunnicliffe - Univerity of Victoria

December 08, 2014

NW Eifuku: The Paradox of the Mussel. Video courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NSF/NOAA, Jason, Copyright WHOI. Video produced by Saskia Madlener. Music by Charlie Brooks. Download (mp4, 63.5 MB)

The mussel beds of NW Eifuku are impressive – surely it is a great place to live!!

The hot vent ecosystem depends mostly on energy that microbes derive from chemical reactions in the vent water. Once the microbe captures that energy, it uses it to fix carbon dioxide into glucose – much as a plant does in photosynthesis.

The Jason manipulator arm uses a scoop bag to collect mussels at NW Eifuku. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NSF/NOAA, Jason, Copyright WHOI. Download larger version (jpg, 610 KB).

NW Eifuku is a great site for chemosynthesis as both hydrogen sulphide and carbon dioxide are abundant. While many animals feed directly on the growing microbes, some vent animals have packaged the hard-working microbes inside them where the chemosynthetic food is passed directly to the host.

Squat lobsters, shrimp, and scaleworms crawl on mussels. The squat lobsters appear “hairy” because of bacteria growing on their shells. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NSF/NOAA, Jason, Copyright WHOI. Download larger version (jpg, 229 KB).

The mussel, Bathymodiolus brevior, is one of those hosts with symbiotic bacteria embedded in the gill tissue. Thus, the mussel needs to grow near vent water to supply hydrogen sulphide, oxygen, and carbon dioxide to its symbionts. Similar mussels at vents around the world can dominate the biomass of the community.

There is a large thick bed of mussels carpeting much of the summit of NW Eifuku where adult animals – up to six inches long – pile on top of each other. These animals are 20 years or older so they have sustained their population over decades.

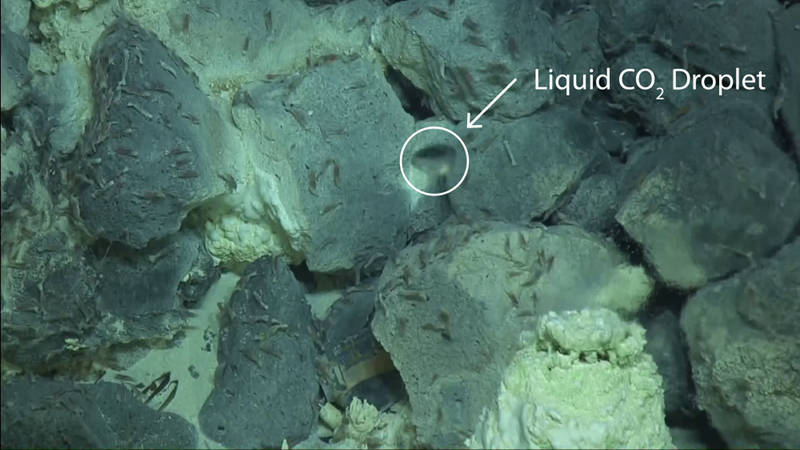

A droplet of liquid CO2 rises from the seafloor in the Champagne vent field at a depth of 1600 meters. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NOAA/PMEL. Download larger version (jpg, 597 KB).

From outward appearances, these mussels seem healthy with their golden shells, no signs of scarring and no ‘cemeteries’ of dead mussels. But appearances are deceiving. These mussels have chosen to live in an acid bath created by the large amounts of carbon dioxide bubbling out through the rocks. NW Eifuku is one of the rare places on Earth where a “natural acidification” experiment is happening – one of the reasons that we are here. The price these animals pay for the access to vent fluids is a life-long struggle to survive and grow.

We scooped up a dead mussel; the meat was still intact but the shell was already mostly dissolved. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NOAA/PMEL. Download image (jpg, 64 KB).

The shells of NW Eifuku mussels are very fragile and so thin, you can see shadows through them. We compared these shells to ones at a high pH (less acidic) site to find the Eifuku mussels are half the thickness and grow half as fast. We also found that, in normal pH, these mussels can withstand scratches and predator attacks that tear the outer organic cover – the gold periostracum. Not so at NW Eifuku; here, as soon as any white shell is exposed, it dissolves. The shell is calcium carbonate, which easily dissolves in acidic water (low pH).

So we only see the survivors with perfect coverings. There are no discarded shells on the seafloor – only decaying husks of the periostracum. It is also very likely these mussels are using a lot of energy to keep their internal tissues pH-balanced.

Our expectation is that we will find relatively poor condition in these mussels: low body mass, lower lipid content, fewer reproducing. While it is amazing they are here, it is at a high cost.