By Bill Chadwick - Oregon State University and NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory

December 06, 2014

NW Eifuku: First Dive. Video courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NSF/NOAA, Jason, Copyright WHOI. Video produced by Saskia Madlener. Music by Charlie Brooks. Download (mp4, 28.1 MB)

NW Eifuku seamount is one of our main focus sites during this research cruise. Why are we so interested in this place?

One thing that’s unique is the extraordinary amount of volcanic carbon dioxide (CO2) that is emitted here – the most of any known submarine volcano in the world. This makes NW Eifuku an ideal natural laboratory for studying the impacts of ocean acidification (in this case, from the volcanic CO2) on marine ecosystems. In addition, the vents are relatively deep (at 1,600 meters, or over 5,200 feet), and so the CO2 comes out as a liquid under that high pressure instead of as a gas.

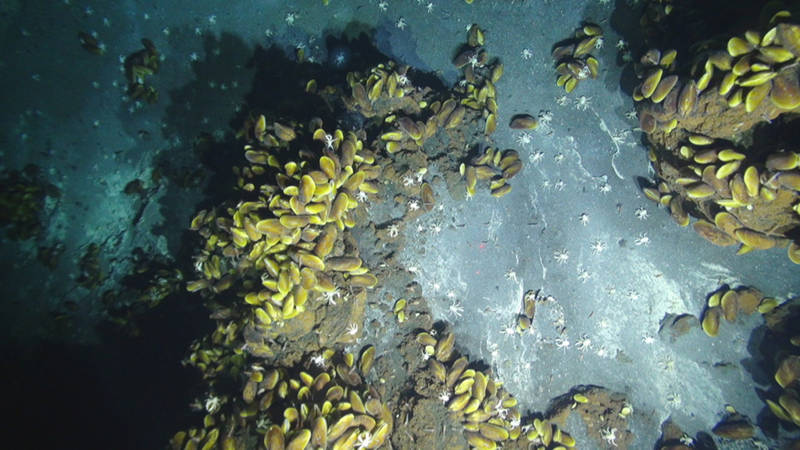

Shrimp crawl on sulfur deposits near Champagne vent at left, near a rock outcrop covered by mussels at right. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NSF/NOAA, Jason, Copyright WHOI. Download larger version (jpg, 570 KB).

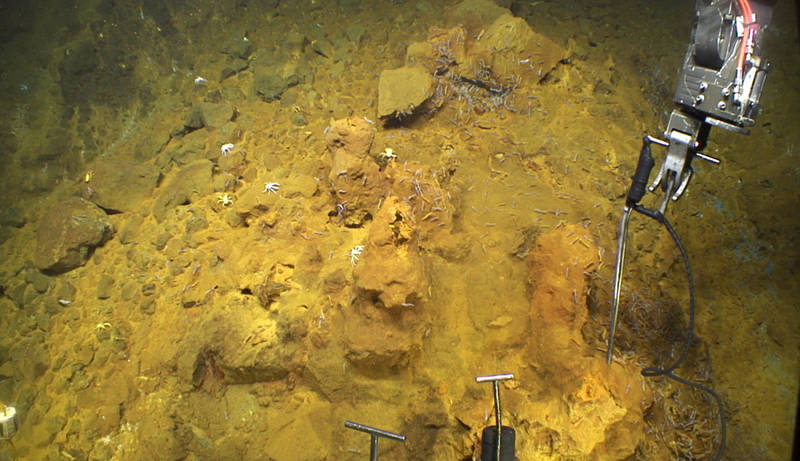

Another characteristic of NW Eifuku is the large areas of diffuse hydrothermal venting which are covered by thick accumulations of iron-loving microbial mats, which will be the focus of the microbiologists in our science team. We’ll discuss their work in more detail in the next Mission Log.

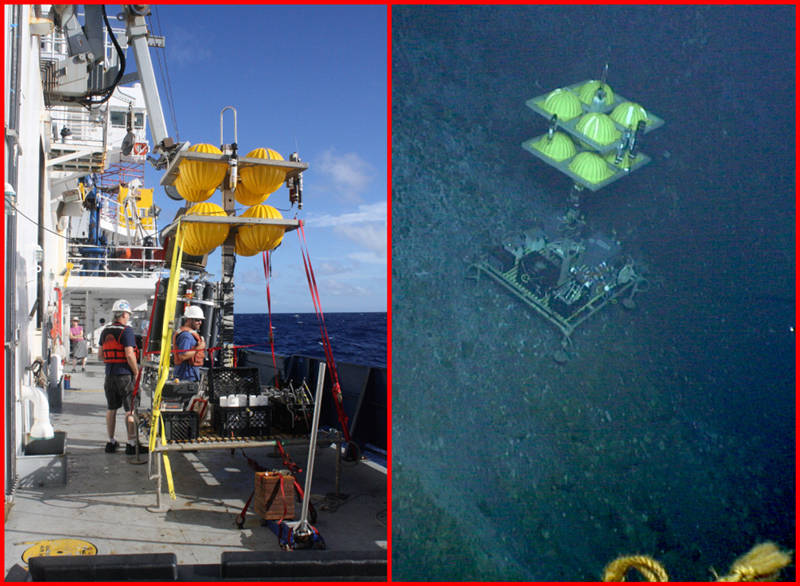

The elevator mooring is ready for deployment on the deck of the ship (left), and then is located on the bottom by Jason (right) so that it can transport equipment and samples to the seafloor and back. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NSF/NOAA, Jason, Copyright WHOI. Download larger version (jpg, 515 KB).

Our second Jason dive of the cruise was here at NW Eifuku and started with us finding the elevator on the seafloor, which we had deployed over the side of the ship just before the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) was launched.

With the elevator located, we proceeded to do a visual survey of the main liquid-CO2 venting site, which is called Champagne Vent. The liquid CO2 droplets are very strange-looking because they appear almost jelly-like and wobble as they rise from the seafloor, a lot like the way giant soap bubbles look, but much smaller. Also, if they touch each other, they stick together like a bunch of grapes instead of combining the way gas bubbles do.

The down-looking camera on Jason shows mussels living on rocky outcrops, while white squat lobsters roam nearby. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NOAA/PMEL. Download larger version (jpg, 429 KB).

Around the Champagne vent field is an amazingly dense biological community that includes huge numbers of chemosynthetic mussels, shrimp, squat lobsters, snails, limpets, and scaleworms. The mussels are particularly interesting because, on the one hand, they are sustained and nourished by the chemistry of the hydrothermal fluids, but on the other hand, the acidic conditions make it very difficult for them to form and maintain their shells. They are really living on the edge and yet appear to be thriving. Some of our experiments will be focused on getting a better understanding of the environmental challenges the mussels face and how they have adapted to survive here.

Another striking aspect of NW Eifuku are the incredibly steep slopes on all sides of the seamount. There are cliffs and knife-edge ridges everywhere that are a bit of a challenge for the ROV pilots.

The Jason manipulator arm measures the temperature of a diffuse hydrothermal vent where iron mats are growing (colored orange) surrounded by shrimp and squat lobsters. Image courtesy of Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NOAA/PMEL. Download larger version (jpg, 527 KB).

After the visual survey of the summit, we collected a suite of vent fluid samples. We then set out a variety of experiments, traps, and samplers that will be recovered on a future dive, and collected microbial mats using a variety of samplers. Many of these samples were returned to the ship by putting them in the elevator mooring and releasing its anchor weight, which allowed it to float back to the surface.

Finally, we started a bathymetric survey using the multibeam sonar on Jason. Such near-bottom surveys can map the seafloor in much higher resolution than we can from the ship at the sea surface. These kinds of maps can make our work on the bottom with Jason much more efficient because they reveal the details of seafloor topography in the areas where we want to work.

Unfortunately, we had to end the dive early due to bad weather moving into our area, so we will have to complete some of these tasks on a future dive. Our first look at NW Eifuku during this cruise reminded us of what a special place it is and made us anxious to return to continue our studies of this weird and wonderful underwater landscape.