Watch a slide show of what may be new marine species, discovered in the world's most biologically diverse region — the Celebes Sea in the southern Philippines.

![]() Click

image to view a slide show.

Click

image to view a slide show.

This slide show illustrates life aboard the BRP Hydrographer Presbitero. See how the team lived as they searched for new species in the deep waters of the Celebes Sea.

![]() Click

image to view a slide show.

Click

image to view a slide show.

Mission Summary

October 15, 2007

Larry Madin

Chief Scientist – Exploring the Inner Space of the Celebes Sea 2007

It’s 10 o'clock on Monday night, and we’re heading back to Manila after 10 intensive days in the Celebes Sea. By mid-morning we’ll be back in the hustle of the sprawling metropolis, trying to finish packing our equipment, get cleaned up, have lunch in a restaurant. We need to get back to the ship in time for a visit by the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) administrator, the U.S. ambassador to the Philippines, a high school class, and other guests from universities and government agencies. They all want to hear about what we have found and experienced during this expedition. The last two days of transit back from the Celebes have been relaxing, but now things will get frenetic again until everything we brought is packed back into shipping containers and on its way home.

These last two days have provided a chance to think about what we were able to do. We accomplished most of our goals, getting an excellent impression of the diversity and abundance of life in the water column, and even on the bottom of the Celebes Sea.

The Global Explorer remotely operated vehicle (ROV) was the star of the show. It performed very well despite strong currents and unexpected underwater snares. Pilots Joe Caba and Toshi Mikagawa took us virtually down to the bottom of the sea, while we remained in the relative comfort of our shipboard control room, and helped us to record and collect some beautiful and fascinating animals. We had hypothesized that the Celebes Sea might hold unusual or unknown species, due to its history of isolation over geologic time and the absence of any previous exploration in deep water. Many of the species we saw in the top 1,000 meters (m) were the same ones we knew from other oceans. We tried to collect enough of them so that experts could examine them closely to see if they really were the same, or different enough to be considered a different species.

When we got down nearer the bottom with the ROV, we encountered the most unusual and unfamiliar animal of all. When we first spotted it, people watching the video called out "squid," "no, shrimp," "maybe a fish," "I think it’s a worm." It did turn out to be a worm, but like nothing we had ever seen before. A worm almost 10 centimeters long, swimming with a row of paddles formed from stiff bristles, and with 10 long, writhing tentacles coming out of its head. No wonder we thought it could be a squid! We did end up calling it the "squidworm." We think it may be an undescribed species, but none of us are experts on polychaete worms, so we’ll have to wait until a real specialist can tell us more about it.

Another unusual find was the black ctenophore. Usually ctenophores exist way up in the water column, and they are mainly transparent. Cruising just above the bottom with the ROV, we saw a black blob hovering over the sand. At first we though it was a coconut shell – we’d been seeing many of them on the bottom — but a closer look showed us it was a big lobate ctenophore, absolutely black, hovering motionlessly just centimeters above the bottom. It was tough to collect it in one piece, but Joe and Russ Hopcroft persisted and ended up with two of them. This is probably an undescribed species, although something similar has been seen in Japan.

Higher up in the water, we found medusae, siphonophores, swimming sea cucumbers, and isopod crustaceans that look like huge spiders and crawl through the water with incredibly long legs. Another odd organism is the phaeodarian radiolarian, a spherical colony of single-celled organisms. The colonies are attached to lacy glass spheres made of silica rods and assembled like a geodesic dome. Maybe most abundant of all were the "houses" made by appendicularians, small tadpole-shaped tunicates. These houses are round mucous structures that help the animal filter small particles from the water to eat. Appendicularians make new houses frequently, and the sea is filled with both the occupied and abandoned ones, which all slowly sink into the deep ocean.

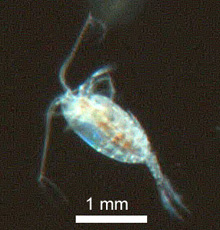

Up closer to the surface, the scuba divers were finding a wide variety of jelly animals — medusae, siphonophores, ctenophores, and salps. We made nine dives altogether, including one at night. Here we found some familiar species and some new to us. Most are probably not undescribed, but again we have to look at them more closely to be sure. Some of the smaller zooplankton that divers can’t see are collected by the bongo net, and Russ Hopcroft took some beautiful photos through the microscope of animals only a few millimeters long. The video plankton recorder also took pictures of these creatures, but underwater, using a special strobe illuminator and sensitive video camera. For larger animals, we fished our trawl net down to about 1,000 m, bringing back black midwater fish, bright red shrimp, and purple medusae.

The RopeCams are meant to attract and photograph some of the biggest and most elusive predators and scavengers – sharks, squid, big crustaceans and various bottom-living fish. We put the RopeCams out four times, but unfortunately only got them back twice. We don’t know for sure what happened to them, but assume they got stuck in rock formations on the bottom and couldn’t be pulled free. When we tried to pull them up, the rope snapped, leaving the cameras on the bottom forever. But the ones we got back showed fish and one big crab gathered around the bait, so we know there are larger animals there than those we saw from the ROV.

Not everything worked as planned, but that is not unusual for oceanographic work. We were lucky with the weather — the seas were as flat and calm for the entire time as any of us had ever seen before. That certainly made everything easier, but still the equipment, the ship and the sea held some surprises. Probably the scariest moment was when the "clump weight" for the ROV, a heavy weight hanging down from the ship to which the flexible ROV tether connects, got snagged on a stray rope in the water at 1,400 m. The rope may have been anchoring a fish aggregating device (FAD) that broke free, leaving a long, heavy line anchored at the ends but floating up like a big snare loop. It snared our ROV, and we wondered if we would be able to get it back. With no way to cut the rope away, we had to slowly bring the weight to the surface. Because of the extra tension from the snagged line, our winch would overheat trying to pull it up, and we had to allow it to cool off after a few tens of meters. Eventually we got it back, cut away the rope, and recovered our ROV with its samples.

There were various other problems during the cruise, but at the end of it we did get much of what we wanted. We had made the first use of a deep ROV in the Celebes Sea, and perhaps in all of the Philippines. We found fascinating animals, some familiar, some possibly new. We put together from all our samplers a pretty complete picture of the variety of zooplankton, fishes, and benthic creatures of this area. And we all found rewarding companionship and fun with our colleagues and friends from U.S. and the Philippines.