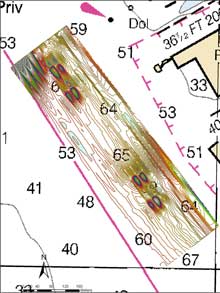

Composite sonar image taken by the NOAA survey vessel Bay Hydrographer on February 15, 2006, showing the current condition of USS Cumberland. The wreck site faces west to east at the bottom of Hampton Roads. Image courtesy of NOAA. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Colored lithograph of the Sinking of the Cumberland by Currier and Ives, 1862. Used as the back of the Cumberland Club T-shirt, with the phrase “Destroyed but not Conquered” written below. US Naval Historical Center photograph. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Brief History of the USS Cumberland

Gordon Calhoun

Historian/Daybook Editor

Hampton Roads Naval Museum

The third most famous ship in the Battle of Hampton Roads was the sloop-of-war USS Cumberland. Most well known for her 90-minute battle with the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia, the vessel served her country for 20 years prior to her destruction on March 8, 1862.

Cumberland began her career in the U.S. Navy as a 50-gun sailing frigate. Designed by famed American designer William Doughty, Cumberland was one of a series of frigates in the Potomac-class. The class borrowed heavily from older American frigate designs, such as Constitution. Specifically, Doughty liked the idea of giving a frigate more guns than European designs called for. As a result, he called for Cumberland to have a fully armed spar deck, along with guns on the gun deck. She was launched May 24, 1842, at the Boston Navy Yard ![]() .

.

For her first mission, the ship sailed to several parts of the Mediterranean, including Port Mahon, Genoa, Naples, Toulon, Jaffa, and Alexandria. The cruise was largely uneventful, though there was a diplomatic scuffle with the Sultan of Morocco who refused to recognize the newly appointed American ambassador. The most notable event was Lieutenant Andrew Foote's successful effort to ban the grog (rum) ration. It later became Department policy in 1862, and it is still in effect to this day (with some exceptions).

As Cumberland was being made ready for a second trip to the Mediterranean, she was ordered to Mexico. Here she was flagship of the Home Squadron ![]() between February and December 1846, serving in the Gulf of Mexico

between February and December 1846, serving in the Gulf of Mexico ![]() during the Mexican-American War

during the Mexican-American War ![]() . The ship oversaw the blockade of the eastern Mexican coast for most of the war. She participated in several attacks on Mexican ports before running aground on July 28 off the coast of Alvarado. Damage from the grounding forced her to retire to Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs.

. The ship oversaw the blockade of the eastern Mexican coast for most of the war. She participated in several attacks on Mexican ports before running aground on July 28 off the coast of Alvarado. Damage from the grounding forced her to retire to Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs.

Cumberland returned to Mexico just as a cease-fire was in place. Commodore William Perry ![]() took over as flag officer. Operating from Cumberland, Perry was instructed by President Polk’s Administration to assist settlers fleeing a major Mayan insurrection (known as the Caste War of Yucatán

took over as flag officer. Operating from Cumberland, Perry was instructed by President Polk’s Administration to assist settlers fleeing a major Mayan insurrection (known as the Caste War of Yucatán ![]() ). Fortunately for “Old Bruin” (Perry), he was allowed leave the region after the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo

). Fortunately for “Old Bruin” (Perry), he was allowed leave the region after the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo ![]() had been ratified.

had been ratified.

Cumberland made her second cruise to the Mediterranean from 1849 to 1851, followed by a third cruise after a short refit in Boston. Cumberland's primary mission during these two cruises was to uphold American neutrality during a very turbulent period in European history. This was accomplished by assisting American diplomats, merchants, and increasingly large numbers of American missionaries in Italy, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire.

Between 1855 and 1857, Cumberland was razeed at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston, transitioning from a frigate into a sloop-of-war. Shipyard workers removed the top deck, quarter galleries, all guns from the spar deck, and several sections of wood to make her a lighter and thus slightly faster ship. Her gun deck was re-armed with 24 smoothbore Dahlgrens, a more powerful cannon.

From 1857 to 1859, she cruised off the coast of Africa ![]() as flagship of the African Squadron

as flagship of the African Squadron ![]() , patrolling for the suppression of the slave trade. Like many U.S. Navy ships in Africa, Cumberland employed a number of Krooman (tribesman of Liberia and the adjacent coast) to serve as scouts, interpreters, and fishermen. The ship's surgeons dealt with a number of issues, including an outbreak of smallpox. Cumberland crewmen boarded several dozen merchant ships, but seized only one — the schooner Cortez — after shackles and known slave-trading items had been found on the deck of the schooner.

, patrolling for the suppression of the slave trade. Like many U.S. Navy ships in Africa, Cumberland employed a number of Krooman (tribesman of Liberia and the adjacent coast) to serve as scouts, interpreters, and fishermen. The ship's surgeons dealt with a number of issues, including an outbreak of smallpox. Cumberland crewmen boarded several dozen merchant ships, but seized only one — the schooner Cortez — after shackles and known slave-trading items had been found on the deck of the schooner.

Map of the event of the Battle of Hampton Roads. Illustrated by Jacob Wells, from the book Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume I. Published 1887-1888 by The Century Co., New York. Click image for larger view and image credit.

This 2005 contour map shows the USS Cumberland at the top and the CSS Florida below. Map courtesy of NOAA. Click image for larger view and image credit.

After her return from Africa, Cumberland became flagship of the Home Squadron in 1860 and made a return trip to Vera Cruz, Mexico. When domestic issues in the United States took a turn for the worse, the U.S. Navy recalled Cumberland to Hampton Roads ![]() . At the outbreak of the American Civil War

. At the outbreak of the American Civil War ![]() Cumberland was at the Gosport Navy Yard

Cumberland was at the Gosport Navy Yard ![]() , Virginia, one of the new Confederate states, with orders to monitor the situation in Norfolk and Portsmouth. After the attack on Fort Sumter, the ship's company was ordered to gather or destroy U.S. Government property.

, Virginia, one of the new Confederate states, with orders to monitor the situation in Norfolk and Portsmouth. After the attack on Fort Sumter, the ship's company was ordered to gather or destroy U.S. Government property.

Cumberland was towed out of the yard by the steam sloop USS Pawnee, escaping destruction when other ships there were scuttled and burned by Union forces on April 20, 1861, to prevent their capture. She sailed back to Boston for repairs. The aft smoothbore Dahlgren was removed and replaced with a 70-pounder rifled pivotgun.

She sailed back to Hampton Roads and served with the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron ![]() . The sloop-of-war engaged Confederate forces in several minor actions in Hampton Roads and captured many small ships in the harbor. She was also a part of the 1861 Hatteras Expedition that captured the forts along the North Carolina coast.

. The sloop-of-war engaged Confederate forces in several minor actions in Hampton Roads and captured many small ships in the harbor. She was also a part of the 1861 Hatteras Expedition that captured the forts along the North Carolina coast.

During the first year of the Civil War, both the Confederate and Union sides experimented with covering warships in iron armor to make them impervious to cannon fire. As the war progressed, this new type of vessel proved deadly to older wooden ships. CSS Virginia was among the first ironclad ships built by the Confederacy.

On March 8, 1862, as Cumberland lay at anchor in Hampton Roads, watchmen onboard noticed that a squadron of ships approached from the south. The ironclad CSS Virginia steamed slowly up the Elizabeth River towards the blockade squadron. Unable to get out of the way or stop the oncoming Confederate warship, Cumberland was helpless. After exchanging a few shots, Virginia pressed home the attack and smashed her cast-iron ram into the sloop-of-war. More desperate fighting took place, but by 3:35 p.m., Cumberland’s company was given orders to abandon ship.

Cumberland lost 121 men during the battle, including two officers. Cumberland was sunk by Virginia and became a martyr to the Union cause. Several poets and songwriters, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, wrote stirring pieces hailing Cumberland and her acting captain’s (Lieutenant Morris) refusal to surrender in the face of certain death.

Today the wreck of the Cumberland rests quietly at the bottom of Hampton Roads. The ship’s popular legacy is its destruction by the Virginia. But Cumberland’s 20 years of operational service demonstrate the significant role it played in U.S. diplomacy in the Mediterranean and Mexico, and how the U.S. projected Naval power during America’s first century.