Scientists tracked narwhals along Melville Bay in Northwest Greenland. The scientists tagged narwhals with satellite transmitters to determine if they can collect oceanographic data in remote Arctic areas. View a slide show of the scientists' activities.

![]() Click image to view a slide show.

Click image to view a slide show.

Map of cruise track departing from Upernavik and sailing north along the West Greenland coast to Melville Bay. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Narwhals as Oceanographers

Mission Summary from Leg I

September 2006

Melville Bay, Northwest Greenland

Dr. Kristin Laidre, Polar Science Center

Applied Physics Lab, University of Washington

Dr. Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen, Greenland Institute of Natural Resources

The primary goal of this study is to test the feasibility of using narwhals as a platform for collecting oceanographic data in remote inaccessible areas of the Arctic. Whales are captured and instrumented with satellite transmitters that collect detailed data on ocean depth and temperature. The first half of this NOAA Ocean exploration study was completed in September 2006. It entailed a field effort in the northern part of Melville Bay, Northwest Greenland, where narwhals occur in conspicuous numbers in summer. A 19 ton fishing vessel was chartered and sailed out of Upernavik, the closest town to Melville Bay in West Greenland. Two highly experienced Inuit hunters from northern Greenland participated in the operation together with two crew members on the fishing vessel and two biologists responsible for the study. Nets for catching whales were set at five different localities in Melville Bay and were continuously observed 24 hours a day. When whales swam into the nets, they were disentangled from two inflatable boats and stabilized at the surface. The technique for attaching narwhal satellite transmitters has been refined for almost a decade: during a 30 minute period, two nylon pins are cautiously put into the dorsal ride of the whale and satellite tags are attached with wires that wrap around the pins.

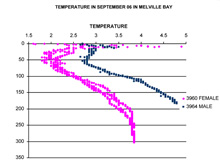

Three whales (one male and two females) were captured and tagged in Melville Bay. The satellite transmitters provide daily geographic positions together with temperature measurements obtained from an external temperature stalk mounted on top of the transmitter. The temperature data are collected each time the whales dive below 100 meters and consist of random samples of temperatures during dives over 1,800 meters. The tracklines of the whales are also useful for identifying regions important to the population and understanding the relationship of the Melville Bay population to neighboring narwhal populations. On the map, movements of the tagged narwhals through September 2006 can be seen. The whales remain in Melville Bay through the end of the month and are generally coastal. Beginning sometime in November, the narwhals are expected to travel rapidly offshore and move to their wintering grounds in Baffin Bay. This wintering ground will be visited by the research team in April 2007, just before the whales head north again. Here scientists will take oceanographic samples (CTD casts) to calibrate the temperatures collected by the whales, deploy more satellite tags on whales, and record acoustics using hydrophones and sonobuoys.

The biggest obstacles on this leg of the expedition were related to the extreme conditions in Melville Bay. This included high winds, large amounts of glacial ice (which resulted in hundreds of icebergs floating into the nets), large tidal cycles (which moved both nets and sea ice in unexpected directions), and the unexpected captures of Greenland sharks in the nets. Given that Melville Bay is the site of many active glaciers, there were large pieces of ice (multiple stories high and city blocks long) constantly drifting past the nets at unpredictable speeds and directions. Once an iceberg was observed to be on course towards the nets, an immediate response from the crew was required to avert the iceberg from sweeping the nets away. Crew members had to go out to icebergs in Zodiacs and use the bow of the boats to push them off course. This usually was combined with cutting off buoys on the float line so the nets would sink below the iceberg. The frequency of fast moving icebergs increased with the full moon and high tide. Occasionally, icebergs stranded on the bottom near the boat and the nets and after some time would explode from inner tension and excessive sunlight, creating a frustrating array of thousands of smaller iceberg everywhere. Occasionally Greenland sharks also became entangled in the nets and had to be carefully removed. The sharks were relatively docile in the cold water, but were hard on bare hands or rubber gloves when being removed from the nets because of their sand-paper like skin. The Greenland shark is a scavenger and not quick enough to catch and eat live animals, but still very big with a full set of teeth. It was critical to remove the sharks from the nets quickly because their presence could be detected by the narwhals and would result in the whales avoiding the nets.