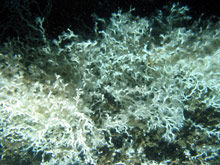

This is a photograph of a patch of hard-bottom habitat in the Gulf of Mexico. In this small area, there are several species of anemones, sponges, a black coral, stony corals and a crab, illustrating the extremely high diversity possible in these ecosystems. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Coral Habitats

Charles Messing

Professor Oceanography

Oceanographic Center

NOVA Southeastern University

Coral reefs--the simple mention of the words conjures images of dazzling seascapes in clear turquoise waters, winding hills and meadows of stony trees and undulating fans somewhere on the vague border between plant and animal, and populated by a bewildering variety of strange and beautiful creatures: bristling lobsters and urchins, boldly-patterned snails, and a dizzying variety of fishes from tiny jewels to sleek, ominous sharks. A further step in our knowledge tells us that such reefs grow only in shallow, warm tropical waters, their coral architects bound to the sun by internal fellow-travelers--microscopic single-celled symbiotic algae that contribute to their coral hosts' nutrition by trapping sunlight via photosynthesis and transferring the energy-rich chemical products of that process to the surrounding coral tissue.

Hidden Reefs

All well and good. But, it turns out that these coral reefs are just the well-known

and easily accessible face of a much larger world of reefs--hidden

from popular view by cold and often very deep ocean waters. Coral reefs actually

occur throughout much of the world's deep oceans: on elevated areas

of seafloor where bottom currents are frequent or strong enough to supply

enough food and prevent burial by accumulating sediments. We find them along

the slopes of continents and islands, on seamounts, and in submarine canyons

and glacial fjords. At high latitudes, they may develop as shallow as 50

meters below the surface. Elsewhere, and especially in the tropics, they

occur over a mile deep.

Lophelia pertusa can form thick branching colonies over large areas, providing hiding places for many different types of animals. Click image for larger view and image credit.

These deep reefs are built by coral species that lack symbiotic algae. As a consequence, they grow much more slowly than their shallow, tropical relatives, and do not recover as easily from the effects of fishing or dredging. Although constructed by relatively few coral species (unlike tropical reefs), these deep reefs are home to an enormous variety of associated creatures--sponges, worms, crustaceans, echinoderms, mollusks and fishes, to name a few--that may rival the diversity of some shallow reefs. It is this associated diversity in particular that challenges us to find out more about these reefs--how and where they grow; what species they harbor, and how these inhabitants interact. Some of these denizens are important food fishes, others may produce pharmaceutically important chemicals, and still others may hold in their skeletons keys to understanding climate changes.

Crossroad in the Sea

The Florida Coast Deep Corals expedition has targeted the deep reefs of the Strait of Florida, the reversed-L-shaped channel that separates Florida, the Bahama Islands and Cuba. We are particularly interested in this region for two reasons. First, deep reefs at low latitudes under tropical waters are poorly known relative to their northern counterparts. Second, the Strait of Florida is unique; it contains numerous distinctly different environments where northern and southern fauna meet to create what may be the greatest diversity of deep-water life in the Atlantic Ocean. Previous expeditions have begun to outline the range of deep-reef habitats in the Strait of Florida. Among other expedition goals, we plan to build on this sparse data by looking at several different deep-reef environments in the Strait to understand how the distributions of corals and other organisms relate to each other and to environmental conditions. To do this, we will photograph, count, map and collect as many species as possible. Our expedition will range from northern Florida to the Florida Keys.

These look like sea fans at first glance, but they are actually a type of sponge that also has a flattened fan shape. The large surface is oriented facing the current to take advantage of food flowing in the water. These types of animals give us an idea of the prevailing current in an area. Click image for larger view and image credit.

A Coral Menagerie

The main players that form the complex three-dimensional habitats of deep reefs

represent several different groups of organisms. All belong to the Phylum Cnidaria--the

great branch of the animal kingdom that includes medusae (jellyfishes)

and anemones as well as corals. All have a basically sac-like body with a mouth

surrounded by tentacles equipped with stinging cells. Any cnidarian with a firm

or rigid, mineral or organic skeleton can be called a coral, although usage is

not consistent (e.g., in soft corals the skeleton consists of small limestone

bits imbedded in their tissues). Stony, or true, corals have solid calcium carbonate

skeletons and anatomical structures arranged in multiples of six; they are the

primary architects of deep (and shallow) reefs. Octocorals, which include the

sea fans, sea plumes, soft corals and bamboo corals, have anatomical structures

arranged in eight parts; their skeletons combine organic and mineral components.

Black corals have an organic skeleton covered with fine thorns. Like stony corals,

lace corals have a solid calcium carbonate skeleton, but they are anatomically

much simpler and, unlike all the others, have a planktonic medusa stage.

The East Coast Pinnacles

Between Jacksonville and Jupiter, FL, nearly 300 mounds from 8 to 168 meters

in height (25-550 ft) crowd the seafloor at depths reaching about 700 meters.

Submersibles and ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles) have confirmed the presence

of deep-sea corals on many of these mounds. The northern sites off Jacksonville

appear to resemble what are called lithoherms--deep-water rocky mounds

built up by corals, skeletons of other organisms and sediments all cemented

together--while further south, the mounds are muddier

and capped with coral thickets. In both areas, the dominant habitat-forming species

are the branching stony corals Lophelia

pertusa, Madrepora oculata and Enallopsammia

profunda, bamboo corals and other octocorals, black corals and sponges.

Much of what we know about these pinnacles and the biology of the next two

study areas was first discovered by a group of researchers headed by John Reed,

one of the scientists on our current Florida Coast Deep Corals expedition team

(Reed et al., 2005; Reed et al., in press).

These are black coral sea whips - another type of coral often found in patches on deepwater hard bottom surfaces. They do not create the intricate habitat formed by corals like Lophelia, but every little bit of shelter is precious if you are small and tasty. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The Miami Terrace

The Miami Terrace is a long rocky platform that lies between Boca Raton and South

Miami at depths of 200-400 meters. It consists of limestone ridges, scarps and

slabs that provide extensive hard bottom habitat. At its eastern edge, a rugged

escarpment is capped with Lophelia pertusa, lace corals, bamboo

and other octocorals, and sponges. In May 2004, John Reed observed dense aggregations

of 50-100 wreckfish here.

The Pourtalès Terrace

Named after Count Louis de Pourtalès, one of the pioneers of American marine

geology, this triangular limestone platform parallels the Florida Keys from

Key Largo to Key West, and its apex extends half way to the Bahamas. Its unusual

geology includes deep-water sinkholes up to 180 meters deep and tall mounds

up to 120 meters high. Some of the latter are well-known to sport fishers for

their rich gatherings of gamefish. Although the lithoherm-type mounds support

many different species of octocorals, black corals and one colonial stony coral

(Solenosmilia

variabilis), many of the species found to the north are absent here. Instead,

the mounds support dense thickets of lace corals. In addition, trawl collections

suggest that the Terrace supports a unique bottom community of invertebrates

rarely found elsewhere in the Strait of Florida.