Dr. Bruno Pernet looks on as crew members recover an acoustic mooring buoy summoned just 15 minutes earlier from the ocean floor. The baskets of mussels that come up with these buoys provide seasonal samples during times when expensive submersibles are not available. Click image for a larger view.

Deep Explorations in Time

October 17, 2002

Craig M. Young

University of Oregon

Cathy Allen

Rutgers University

This morning we dove to the famous Brine Pool, one of the best studied seep sites in the Gulf of Mexico. This was our eighth dive to this site during this single cruise. Why, on a cruise devoted in large measure to exploration, would we spend so much time at a single site? Because we think it is important to have more than a “snapshot” picture of the deep sea floor. We need to understand how things change over time.

Relatively few places on the deep-sea floor have been visited during all different seasons of the year. In fact, until just a few decades ago, scientists believed that conditions in the deep sea were entirely constant and that deep-sea animals experienced no seasons at all. Studies of reproduction have now revealed seasonality in many deep-sea animals. We are visiting the brine pool time and time again over a three-year period to shed light on the way deep-sea animals experience and perceive seasonal changes around them, and how they know when to reproduce.

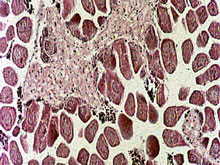

Our study animals at the brine pool are mussels, Bathymodiolus childressi, which occur abundantly all around the edge of the pool. Bacteria in these mussels convert methane to food, so they have an abundant food supply all year round. Mysteriously, however, they produce babies called larvae only at one time of the year. We are seeking evidence of a seasonal food signal falling to the sea floor from the lighted waters above. To obtain mussel samples during seasons when no submersible is available, we use modern instruments called acoustic releases to call up cages of mussels from the surface. Large white buoys marked by bright orange flags pop to the surface dragging cages of mussels behind. After the ship picks up the buoy, we dissect the mussels to obtain samples of their various tissues and organs. These tissues are analyzed to see how they are developing and for lipids (fats) and stable isotopes that tell us if the mussels supplement their nutrition with plankton when it is available.

Johnson-Sea-Link submersible, just before descent. The acoustic moorings are dropped to the sea floor with a pinger attached. The sub then finds the mooring, moves it into position near the brine pool, attaches a cage and fills the cage with mussels. The mooring will be recovered by remote sound signals many months laters. Click image for a larger view.

We are able to determine the maturity of eggs and sperm in mussels by cutting thin slices through the reproductive organs, staining them and looking at them under a microscope: a technique called histology. We can tell where the energy for reproduction came from by analyzing the fatty tissues. Like many animals, mussels store energy from food in the form of fats. All fats are composed of building blocks called fatty acids. The types and shapes of fatty acids produced by bacteria in mussels are different than those in food from the surface. You are what you eat (well almost!), so by looking at the kinds of fatty acids in mussels (and their stable isotopes), we are able to tell whether their food comes from their bacteria or from the surface.

Today’s dive was mostly spent arranging the underwater acoustic buoys and filling up the cages with mussels. This was a good use of the dive, since it will allow us to “explore” the site in four different months, while only bringing an expensive submersible to the site once.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.