Christina Ramirez, University of Washington Applied Physics Lab

Seagliders are autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that dive to 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) under the water. All Seagliders are equipped with sensors that measure the temperature and salinity in the ocean and some have additional sensors that record chlorophyll, currents, sound, radiation, etc. Seagliders are special among autonomous vehicles because they can continue to dive in the ocean on their own for about nine months at a time while communicating with the pilot's computer via satellite over an iridium satellite network.

Each time the Seaglider comes to the surface, it receives its location via GPS. This position is sent to the pilot along with data from other sensors and all internal diagnostic information related to the health of the Seaglider. The Seaglider then will download new coordinates of the navigation targets, new sampling patterns, and underwater flight patterns. The pilot is on land and can talk to the Seaglider from anywhere!

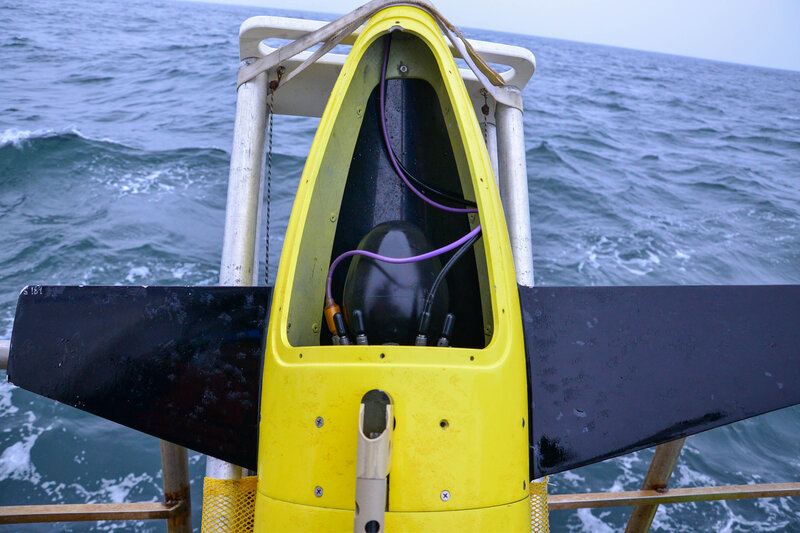

Different from many other AUVs, Seagliders don’t have a propeller and rely on buoyancy to go up and down in the water. Since we know exactly how much the Seaglider weighs, we change the amount of buoyancy by changing the volume of the vehicle. Just like when you’re in the water with your head above water, when you take a deep breath, your lungs inflate and your body rises; when you exhale and let out the air, your body sinks. The Seaglider uses oil to change its volume. When trying to move up in the water column, the Seaglider pumps oil from the inside of its reservoir to an external bladder (Figure 1). This changes the total volume and makes it more buoyant than the water around it. When trying to dive down, the Seaglider pumps the oil in the bladder into an internal reservoir. This decreases the total volume of the Seaglider so it starts to sink. As it changes its buoyancy, the Seaglider uses a large lithium battery inside to point its nose down or up and the wings on the outside of the vehicle to maintain its forward motion. The Seaglider can also rotate the lithium battery to take right or left turns (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Oil bladder used to control the buoyancy of the Seaglider being used during the Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders expedition. This bladder appears fully inflated (bulb in the middle of the open hatch), meaning it is full of oil and would move the Seaglider up in the water column if the vehicle was underwater. Image courtesy of Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders. Download largest version (jpg, 805 KB).

Figure 2: Mass shifter of the Seaglider being used during the Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders expedition. The mass shifter consists of Seaglider’s lithium battery pack which allows it to change directions by moving its mass. Image courtesy of Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders. Download largest version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

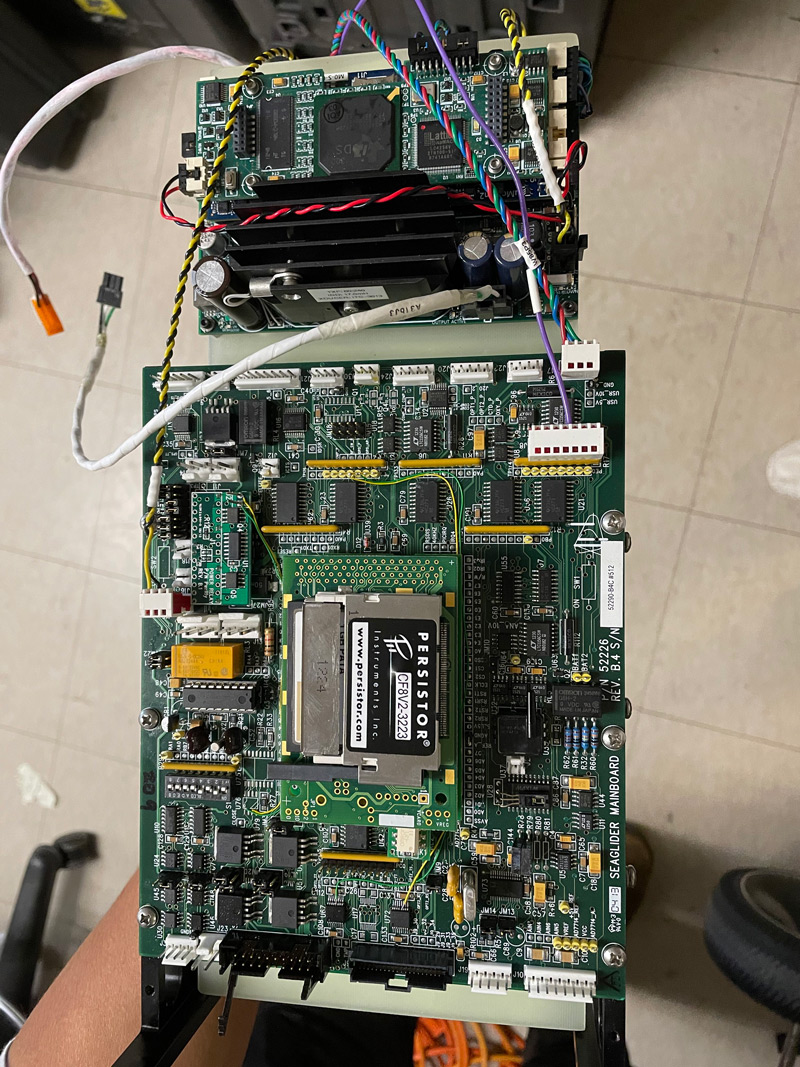

Figure 3: The “brain” of the Seaglider being used during the Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders expedition. Here you can see the electronics board that allows the Seaglider to make its movements and power its functions. Image courtesy of Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders. Download largest version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

All the Seaglider movements are controlled by its electronic systems, which are essentially the “brain” of the Seaglider (Figure 3), all housed in a pressure hull called a “pupa” because it looks like an aluminum butterfly pupa (Figure 4). The pupa is only a cylinder-like casing, so the wings, rudder, antennae, and all other sensors are attached to a smooth fairing on the outside covering the pupa. All these together make a total Seaglider that weighs approximately 54 kilograms (120 pounds), depending on how many sensors are attached. It’s just heavy enough for two people to handle it for deployment and recovery when out at sea.

Figure 4: All of the main parts of the Seaglider being used during the Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders expedition are contained inside a pressure hull, called a pupa given its resemblance to a butterfly pupa! Image courtesy of Coordinated Simultaneous Physical-Biological Sampling Using ADCP-Equipped Ocean Gliders. Download largest version (jpg, 2.0 MB).

After each deployment, Seagliders are brought back to the lab where they are refurbished for the next project. Many Seagliders out there were built originally about 15 years ago and are still running, making these AUVs incredible tools for ocean science data collection.

Published October 20, 2021