2023 Shakedown + EXPRESS West Coast Exploration

(EX2301)

A Tale of Two Canyons: How the Geology in Quinault and Nitinat Canyons Impact Their Unique Biology

Submarine canyons provide an excellent opportunity to study both geology and biology – geologists are interested in the history recorded in the incised wall outcrops, while biologists are interested in the benthic (seafloor) communities that reside on these hard walls. During the 2023 Shakedown + EXPRESS West Coast Exploration expedition, we were able to explore two submarine canyons off the coast of Washington: Quinault Canyon to the south and Nitinat Canyon to the north. Our time in both canyons revealed stark geological and biological differences, which was surprising given their relatively similar methods of formation and proximity along the Washington coast.

Offshore Washington along the Cascadian coast, there are many submarine canyons that cut through the continental shelf. These canyons serve as drainage artifacts created about 12,000 years ago during the last glacial maximum. During this time, glaciers covered about 25% of the Earth’s land surface and the sea level was about 400 meters (1,312 feet) lower than it is today. As these large glaciers melted and migrated northward, they dispensed massive amounts of water and rock debris, forming the canyons we see offshore today. Due to their high relief and location within the loosely sedimented continental margin, these canyons continue to be cut by turbidites (fine-grained sediment deposited by turbidity currents) and unstable slope failures that maintain the canyon geomorphology.

Quinault Canyon

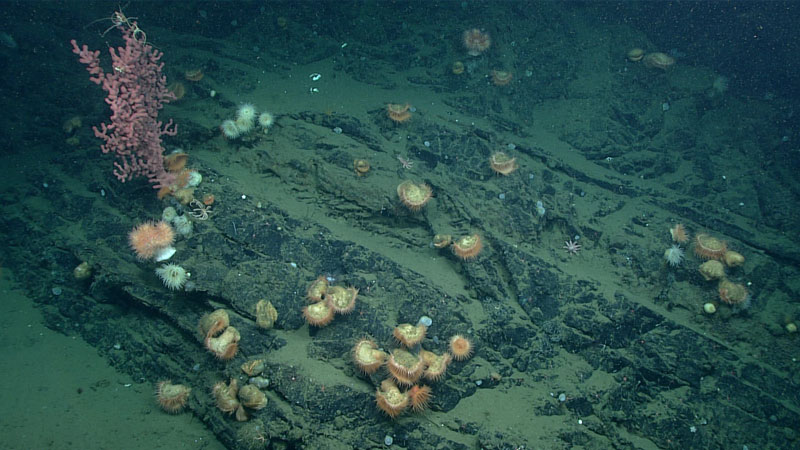

During Dive 07, we explored Quinault Canyon, located offshore southern Washington, and were amazed by the diverse biology and hard rocky outcrops. At the base of the canyon, there was heavy sedimentation of silt and mud covering the ocean floor, accompanied by many brittle sea stars and sea cucumbers. Right away we were welcomed by several "big red jellies" (Tiburonia granrojo) floating at the bottom of the canyon. As we ascended up slope into more cemented, rockier outcrops, we noticed 40-50 different "fly trap" anemone individuals (Actinoscyphia aurelia) and a diverse variety of corals and sponges, including a big "bubblegum coral" (Paragorgia arborea) individual. These coral species are slow to grow by nature and the size of this particular coral suggests that it had been latched onto the hard rock at the base for a long time.

Nitinat Canyon

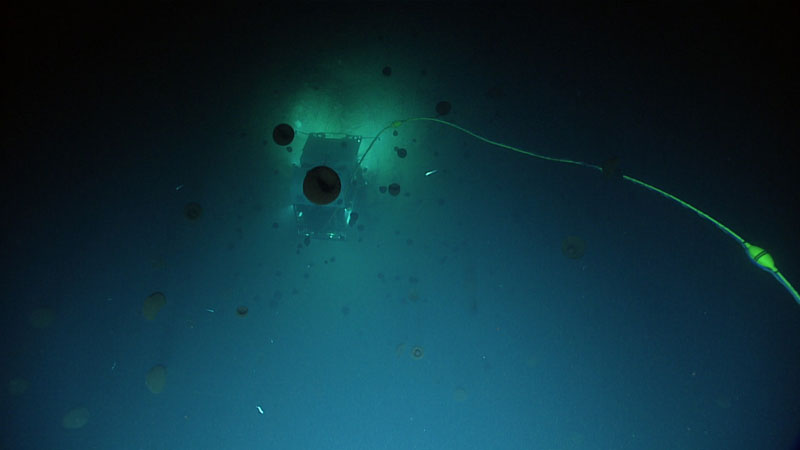

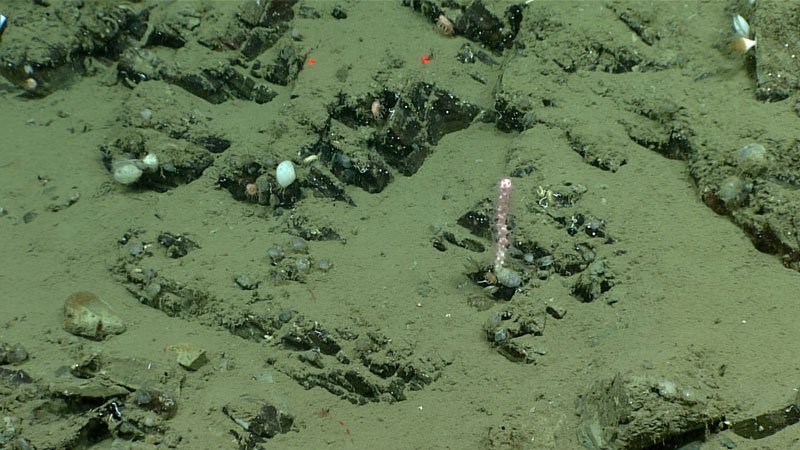

On Dive 08, conducted the day after the Quinault Canyon dive, we headed north up the Washington coast to Nitinat Canyon, which lies outboard the Strait of Juan de Fuca bordering Vancouver Island, Canada. Given the wide biodiversity we saw in Quinault Canyon the day prior, we anticipated hard rocky outcrops again along the canyon walls. While we were again greeted with a high density of pelagic (water column) diversity, on bottom we saw a heavily eroded landscape with loosely consolidated sediment containing vacant bivalve boreholes and scattering of broken shell remnants. Living within these loose rock layers were many squat lobsters and crabs.

Large portions of the slope wall appeared recently slumped off and the portions that were intact were covered by a thick layer of silt and clay sediment. There were several locations where glacial erratic (rocks deposited by glaciers) was embedded into the rock slope, which could be seen protruding out of the wall. A large number of the sponges and corals we saw were bunched up all together on these sparse, hard rock, glacial erratic surfaces. Likely these species latched on to this stable home amidst a largely eroded landscape. While we continued to see a diverse array of coral and sponge species in Nitinat Canyon, the species individuals were not as largely grown as we saw in Quinault Canyon.

Why the Differences?

While Nitinat Canyon has high nutrient availability from down-going currents through the canyon, it also frequently experiences large, magnitude 6 earthquakes. The continuous nature of these earthquakes leads to frequent erosion in the canyon walls and further perturbes the species who rely on a stable, hard substrate in order to grow and thrive. The lack of hard rock within Nitinat Canyon was a physical result of continuous earthquake activity and subsequent erosion of the submarine canyon walls. This in turn impacts the biodiversity in this region – without a hard rock to place themselves on for long periods of time, corals and sponges can’t continue to grow.

The difference in biodiversity between Quinault and Nitinat Canyons reflects the complex relationship between geology and biology of these ancient submarine canyon structures.

By Paige Koenig, Science Co-Lead (Geology), Western Washington University

Published May 2, 2023